Review: From the mouth of the man himself, ‘De Palma’ examines a filmmaker’s evolutions and obsessions

Love him or loathe him, and people have regularly done both, there’s never been doubt that director Brian De Palma is a filmmaker down to his fingertips. “De Palma,” the documentary with his name on it, expertly explores just what that means.

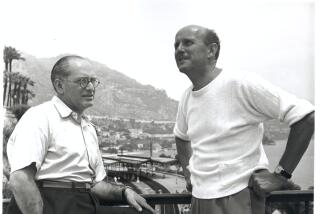

The picture’s co-directors, Noah Baumbach and Jake Paltrow, both have personal relationships with the controversial filmmaker behind everything from “Sisters” and “Obsession” to “Scarface,” “The Untouchables” and “Mission: Impossible.”

So, though Baumbach and Paltrow aren’t heard and don’t appear on-screen, their doc very much has the form of a conversation between friends and colleagues, with De Palma, and De Palma alone, talking to the camera about the work he’s done and why and how he’s done it.

More than talk, there is footage from each of De Palma’s more than 30 works, including the unlikely Bruce Springsteen “Dancing in the Dark” video he directed that features Courteney Cox.

Even more than his own work, De Palma, an omnivorous cinephile, introduces clips from 25 films that have influenced him in one way or another, from Alfred Hitchcock’s “Vertigo” (“I will never forget it”) to Stanley Kubrick’s “Barry Lyndon,” which he admires for the way its camera work slows down time to allow viewers to get into the rhythms of a bygone century.

“De Palma’s” biggest asset, not surprisingly, is the man himself. A formidable talker who is invariably smart, candid and acerbic, De Palma is a person of considerable self-confidence, and listening to him hold forth gives us an always-involving glimpse inside a singular cinematic mind.

A bravura director with a virtuosic visual style, De Palma does not directly address the debate that has grown up around his films for their violence, especially toward women, but you do get a sense of a man with strong creative drives determined to keep making movies no matter what. “Anyone who has a career,” he says, “it’s a miracle.”

And, aware that the way he and colleagues like Steven Spielberg, George Lucas and Martin Scorsese took over the Hollywood system in the 1970s was unprecedented (“What we did in our generation will never be duplicated”), De Palma tends to take all criticism with a grain of salt. “You’re judged,” he says, “by the fashions of the day.”

What De Palma does best is tell war stories about his movie experience, which has been extensive. He worked regularly with singular talents like composer Bernard Herrmann and cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond, he made sure a reluctant Orson Welles learned his lines on “Get to Know Your Rabbit,” and his memorable stories cut across all his films. For instance:

“Obsession.” Cliff Robertson, noticing that costar Geneviève Bujold was stealing the picture, attempted to sabotage her performance.

“Dressed to Kill.” The movie’s plot of a young photographer following and photographing a criminal was inspired by De Palma’s own youthful experience doing the same with his philandering father.

“Body Double.” Porn star Annette Havens was tested for the role that eventually went to Melanie Griffith, freaking out the studio.

“Scarface.” One reason for all the varieties of violence is that De Palma had two weeks to kill, so to speak, while star Al Pacino recovered from an on-set accident.

“The Untouchables.” Robert De Niro took the role of Al Capone after weeks of wavering and insisted on wearing the same kind of silk underwear the mob boss had worn.

“Casualties of War.” Sean Penn was always in co-star Michael J. Fox’s face, taunting him on camera by whispering “television actor” in his ear.

It’s also fascinating to hear De Palma’s uncompromising verdicts on his films, whether they be unhappiness with “The Bonfire of the Vanities” (“I made a lot of compromises; it was a disaster”) or his satisfaction with “Carlito’s Way” (“I can’t make a better picture than this”).

What is not in question about De Palma is his unquenchable passion for film. He knows that if he had told the truth to the women in his life, he would have said to them, “My true wife is my movies, not you.”

No MPAA rating. Running time: 1 hour, 51 minutes. Playing Landmark, West Los Angeles.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.