Cannes diary 2017: ‘The Square’ provoked, ‘Florida Project’ thrilled and Nicole Kidman was everywhere with Colin Farrell

At the 70th edition of the Cannes Film Festival, recently concluded on May 28, L.A. Times film critic Justin Chang took in the scene and all the movies he could watch on very little sleep. In this, his Cannes diary, he gives us an up-close view of one of the world’s most glamorous events, a mecca for film lovers.

DAY 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6-7 | 8 | 9-10

The 70th Festival de Cannes has ended and Pedro Almodóvar’s jury has rendered its verdict, which you can read about in my report on the closing-night awards ceremony. And rest assured, this year there will be no indignant screed against their decisions from yours truly. What’s remarkable about this festival is that, even with a much less impressive competition than last year’s, the jury managed to come up with a much more discerning and satisfying set of winners.

Not entirely satisfying, of course: My personal choice for the Palme d’Or would probably have been “Loveless,” followed closely by “A Gentle Creature” (what can I say, it’s been a good year for devastating portraits of modern-day Russia), and I regret that the Safdie brothers and Robert Pattinson won nothing for their sensationally entertaining “Good Time.”

But in the end, I can't fault a jury for honoring a film as provocative as “The Square,” as moving as “120 Beats Per Minute” or as stylishly single-minded as “You Were Never Really Here.” A title that more or less captures what it would probably feel like to be in Cannes now — once more a sleepy beachside town, with the red carpets rolled up and the metal detectors stowed away for another year. Until then ...

‘A Gentle Creature,’ ‘Good Time’ and ‘You Were Never Really Here’ bring late highs to a middling competition

Based on a highly selective and unscientific sampling of opinions on the Croisette, the general consensus is that while this may be a milestone 70th-anniversary year for the Festival de Cannes, it’s been a disappointing set of films overall, with one of the weaker competition slates in recent memory.

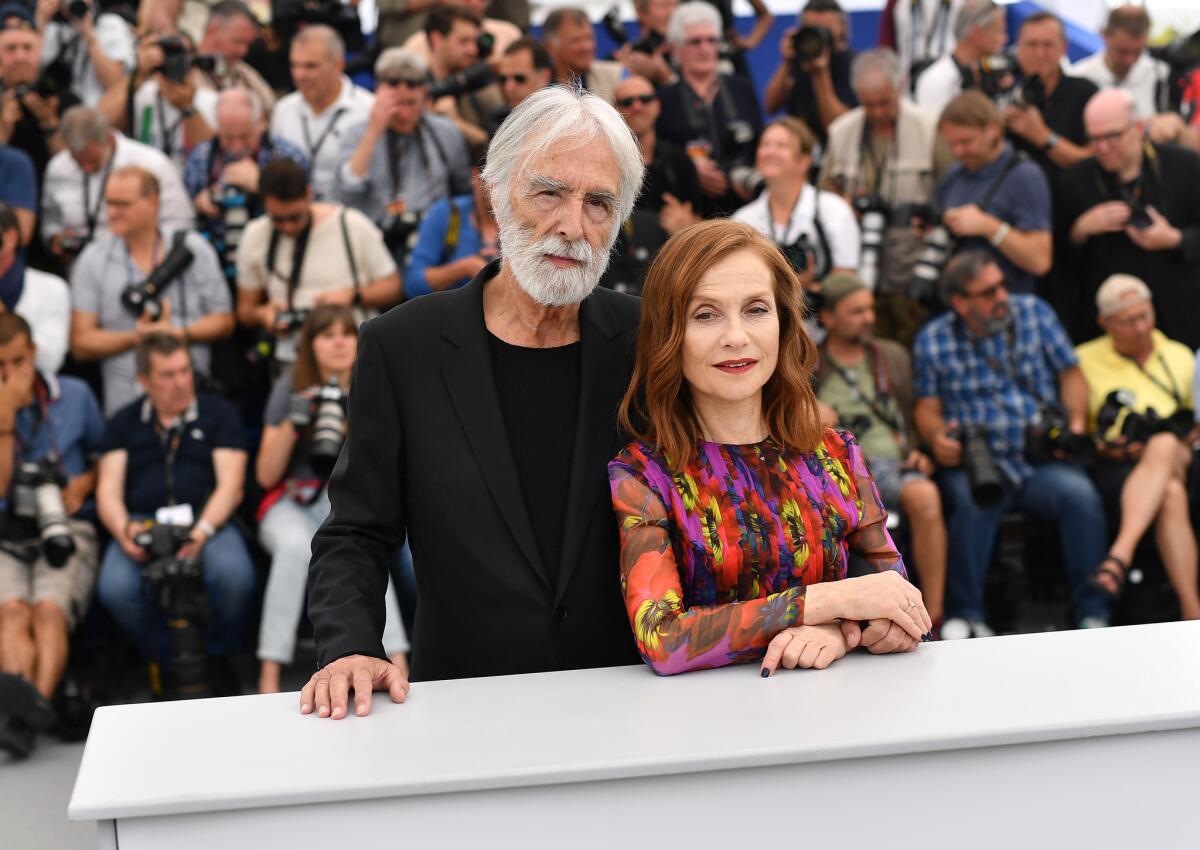

That’s not to say there haven’t been good and even very good movies, only that they’ve been fewer and farther between. The charge of excitement delivered last year by the likes of “Toni Erdmann,” “Elle,” “Paterson,” “The Handmaiden,” “American Honey,” “Aquarius” and “Personal Shopper” — bold, confident visions all, regardless of what you may think of them individually — has struggled to reproduce itself here.

And yet — as always, a blanket sense of disappointment doesn’t tell the whole story. The highs may not have been stratospheric this year, but there have been highs nonetheless. One of them, for me, is the Ukrainian filmmaker Sergei Loznitsa’s “A Gentle Creature” (“Krotkoya”), which is unequivocally one of the toughest, darkest and longest movies playing in competition. (Here I must correct an earlier post in which I misidentified “The Square” and “120 Beats Per Minute” as the longest films in competition; at 143 minutes, “A Gentle Creature” belongs in their company.)

Inspired by (though not adapted from) the Dostoevsky short story of the same title, “A Gentle Creature” follows a stoic Russian woman (played with riveting impassivity by Vasilina Makovtseva) trying to get a care package to her convict husband after it is inexplicably returned to her. Rebuffed at her local post office, she decides to travel to the prison and deliver the parcel herself — a journey that will lead her through her a Kafka-esque bureaucratic nightmare and into the very heart of Putin’s Russia, a place where violent absurdity and everyday inhumanity reign.

Loznitsa, making his third appearance in the Cannes competition (after “My Joy” and “In the Fog”), uses richly textured visuals and sustained long shots to usher us alongside this “gentle creature” down the rabbit-hole. That allusion comes from the story itself, whose surreal climax plays like something out of “Alice in Wonderland,” at least until — well, I’ll leave that horror for you to discover. “A Gentle Creature” is about as strange, perplexing and foreign an experience as any I’ve had at the Festival de Cannes, and the reasons that will limit its commercial viability are the very reasons that you should seek it out, if and when it arrives in your local art-house theater.

“A Gentle Creature” screened for the press on Wednesday. With its single most challenging offering out of the way, the competition has seemed to speed toward the finish with several brisk, light-footed genre movies that have been, if not a series of unmitigated delights, then at least something of a relief. That’s not unusual given the track record of Thierry Frémaux, the festival’s general delegate, who has been known to give action movies such as “Drive” and “Death Proof” pride of place in competition. The 2004 selection, one of the first under his reign, included the now-infamous “Oldboy,” whose director, Park Chan-wook, sits on this year’s competition jury.

Among the best of this year’s genre offerings is the aptly titled “Good Time,” which marks the first appearance in competition by the American independent filmmakers Josh and Benny Safdie. (The brothers were previously at Cannes in 2009 with “Daddy Longlegs,” then titled “Go Get Some Rosemary,” which played in the Directors’ Fortnight section.) Their latest is, fittingly enough, a tale of intense brotherly devotion: Benny Safdie plays Nick, a troubled young man who gets dragged into an ill-advised bank robbery by his brother, Connie, a bumbling yet resourceful small-timer played with ferocious agility by a revelatory Robert Pattinson.

“Good Time” opens with a therapy session, jumps ahead to the amateur heist, and then becomes a sustained chase thriller that harks back to the pulpy, scuzzy pleasures of vintage Sidney Lumet and Abel Ferrara. The action is so brisk and kinetic that you may not notice the social insights that the Safdies have so shrewdly tucked into the margins of their story: Nick and Connie may have had a rough upbringing, but the Safdies are not so sympathetic that they overlook their characters’ undeniable privilege and the even more marginalized people they exploit along the way. A24 is releasing “Good Time” in U.S. theaters in August, and it both stands and deserves to earn the Safdie brothers their widest audience to date.

Even more hypnotic in terms of sheer craft is the Amazon Studios release “You Were Never Really Here,” the latest declaratively titled film from the Scottish director Lynne Ramsay (“We Need to Talk About Kevin”). Adapted from a Jonathan Ames novella, the movie stars a heavily bearded Joaquin Phoenix as a severely troubled, hammer-wielding assassin whose latest job will either kill him or give him a reason to keep living.

What follows is a kind of 21st century riff on “Taxi Driver” that morphs, by the end, into a stealth art-house remake of “Logan” — a deranged odyssey across a wide-ranging New York hellscape that combines sleek formal elegance, fatalistic humor, unsparing violence and another gorgeously unnerving score by Jonny Greenwood. Ramsay’s unwillingness to compromise artistically has often run afoul of a bottom-line-minded industry, which explains why “You Were Never Really Here” is only her fourth film in the 18 years since her brilliant, Cannes-premiered debut feature, “Ratcatcher.” Her return seals her standing as one of our most fearless and forceful filmmakers, if not one as prolific as she deserves to be.

Fitting the Hobbesian criteria of nasty, brutish and short — it’s been ruthlessly whittled down from an anticipated 95-minute running time to a terse, diamond-hard 85 minutes — Ramsay’s film brought the competition to an electrifying but polarizing close. Some declared it precisely the tour de force the festival had been waiting for; others stayed behind to loudly boo the film as the lights came up, perhaps repelled by its brutal nihilism or its placement in the competition. I may be crediting them with too much thoughtfulness: It’s entirely possible that they’re verbally incontinent morons who should be banned from ever attending the Cannes Film Festival again.

As thoughts turn toward the jury prizes that will be handed out on Sunday, no film has stood out as a clear frontrunner for the Palme d’Or. If forced to hazard a guess, I would reiterate my suspicion that Robin Campillo’s AIDS-activist drama “120 Beats Per Minute,” one of the competition’s most roundly satisfying emotional experiences, stands the best chance. Meanwhile, Jacques Doillon’s suffocatingly dull and didactic artist biopic “Rodin” must surely rank near the bottom of the list for everyone who saw it. Slow, taxing films are par for the course at a major international film festival, but this inexplicable competition entry is the rare experience to which watching clay dry would be infinitely preferable.

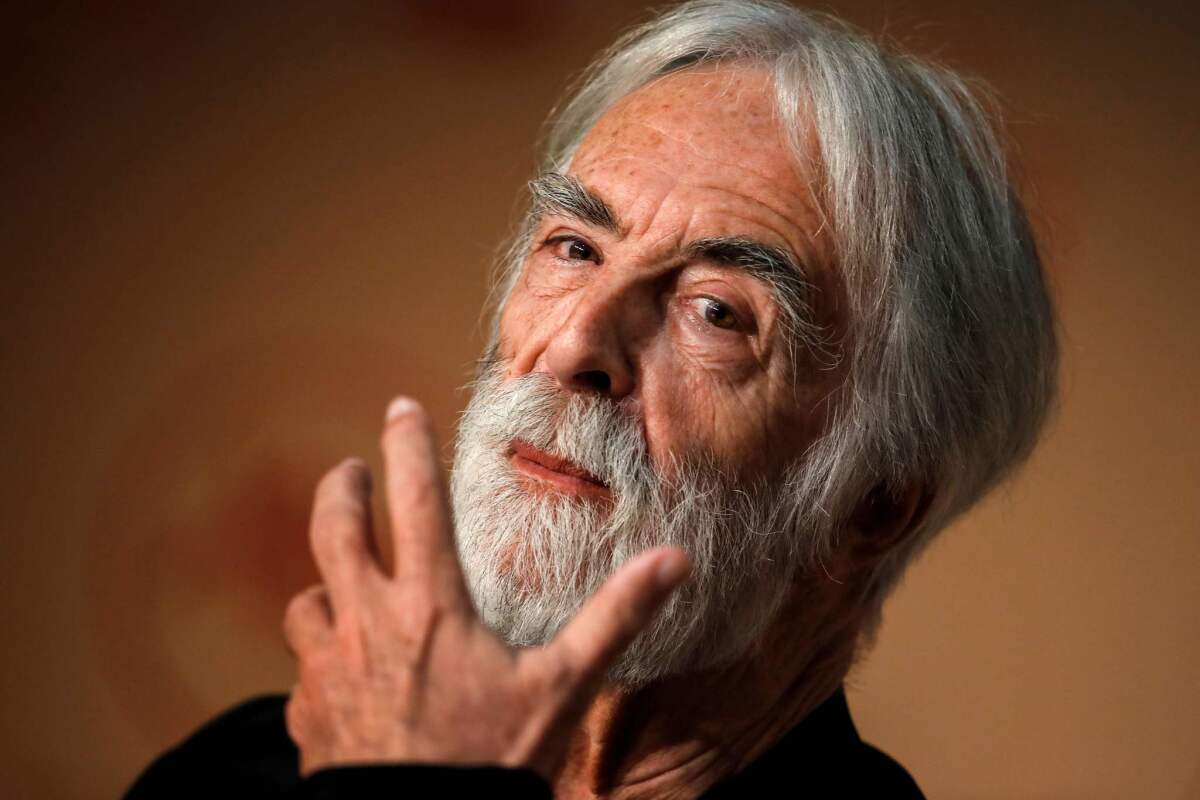

Those seeking a less indulgent portrait of a French artist could lose themselves in the meager charms of Michel Hazanavicius’ “Redoubtable,” a self-consciously playful if largely panache-free sendup of Godard (played by Louis Garrel, with dark sunglasses and a heavy lisp) during his short-lived second marriage to the actress Anne Wiazemsky (an excellent Stacy Martin), who appeared in his film “La Chinoise,” among others. Full of bright primary colors, punny chapter breaks, all manner of meta-winks and other strenuous bits of Godardian business, the movie draws an unambiguous parallel between the disintegration of their relationship and the loss of Godard’s filmmaking mojo as he is swallowed whole by his own surly, disagreeable post-’60s obscurantism.

“Redoubtable’s” critical take on Godard threatened to divide audiences between his fiercest acolytes and those who are convinced he hasn’t made anything watchable since 1967’s “Weekend” (for what it’s worth, I fall into neither category). Still, I can’t imagine even the most diehard Godardian working up enough passion to loathe this self-satisfied pastiche, which has none of the effervescence or stylistic dazzle of Hazanavicius’ Oscar-winning “The Artist.”

Far more deliriously entertaining among the French titles in competition was François Ozon’s “L’Amant Double,” though it’s probably safe to say that few awards are headed its way. Not because it isn’t good, but because it’s exactly the sort of exuberantly disreputable pleasure that could not have been more of a tonic at the end of a long competition. The movie stars Marine Vacth (also in Ozon’s “Young and Beautiful”) as a woman who falls for her therapist (Jérémie Renier), then starts an affair with his identical twin brother (also Renier), a twist that recalls vintage Brian De Palma and David Cronenberg before the film veers sharply sideways into “Rosemary’s Baby” territory.

The result is a marvel of reflective surfaces, feline reaction shots and graphic couplings: a psychoerotic thriller trashterpiece. It also features what may be one of the greatest opening shots in the history of cinema, one that drew gasps, laughs and claps from the audience with its speculum’s-eye view of its central character. I won’t say more, but the non-spoiler-averse among you should check out Kyle Buchanan’s excellent deep dive over at Vulture.

What of the other awards? My personal jury of one would give Pattinson the best actor prize for “Good Time,” and given his impassioned social-media fan base, I frankly pity the man who wins if he doesn’t. Still, he does have strong competition from Claes Bang, the talented Danish discovery who stars in “The Square,” and Nahuel Pérez Biscayart, the terrific Argentinian actor who gives “120 Beats Per Minute” its emotional pulse — and perhaps even from Phoenix and Renier, if the jury is in a playful or adventurous mood.

The actress field, sadly, offers rather fewer options. Ironically in the year that the president of the jury is none other than Pedro Almodóvar, God’s gift to women in the movies, there have been relatively few substantial female roles — certainly nothing to rival last year’s astonishing field, which included Sandra Hüller (“Toni Erdmann”), Isabelle Huppert (“Elle”), Sonia Braga (“Aquarius”), Kristen Stewart (“Personal Shopper”), Ruth Negga (“Loving”) and Sasha Lane (“American Honey”).

One could mount a case for the fine female ensemble of Sofia Coppola’s “The Beguiled,” led by Nicole Kidman, Kirsten Dunst and Elle Fanning, or for two terrific child actresses: Millicent Simmonds in Todd Haynes’ “Wonderstruck” and Ahn Seo-hyun in Bong Joon-ho’s “Okja.” But I suspect that the award will go to Diane Kruger, who gives a ferocious but skillfully modulated lead performance in “In the Fade,” a terrorist-themed revenge drama from the German Turkish director Fatih Akin.

Kruger plays a German woman who loses her Turkish husband and their young son in a bombing staged by neo-Nazi sympathizers. A tense, methodical courtroom drama ensues, followed by a more personal search for justice. Akin’s movie is creaky but absorbing enough to make you look past its implausibilities and one-note characterizations, Kruger’s role being the grand exception. More than one critic likened it to a glorified TV movie; others suggested it was certain to be nominated for a foreign-language film Oscar. Which one of these is the greater insult, I will leave it for you to decide.

‘The Beguiled’ and ‘The Killing of a Sacred Deer’ bring the Colin and Nicole Show to Cannes

Sofia Coppola’s “The Beguiled” had its Cannes world premiere on May 24, exactly 11 years to the day after her prior competition entry, “Marie Antoinette,” played here to a bevy of boos from the press audience. I can still remember that 2006 edition of Cannes (my first), as well as my bewilderment, followed by irritation, that anyone would jeer at a soufflé-light biographical fantasia as inventive and captivating — as beguiling, if you will — as the one we had just seen.

Getting booed at Cannes, of course, is a foolish, arbitrary indignity that has been suffered by any number of masterpieces and even Palme d’Or winners, “Taxi Driver” and “The Tree of Life” among them. Eleven years later, happily, there were no boos for “The Beguiled.” It may be no “Marie Antoinette,” but it adds another deft, distinctive square to Coppola’s finely stitched crazy quilt of a career.

You’ll pardon the embroidery metaphor, which comes straight from the movie itself, a darkly absorbing Southern gothic tale set in 1864, during the fraught final days of the Civil War. “The Beguiled” shares both a title and a source text (Thomas P. Cullinan’s 1966 novel, “A Painted Devil”) with Don Siegel’s deliciously pulpy 1971 melodrama, which starred Clint Eastwood as a wounded Union soldier who holes up in a house full of young Southern belles.

In Coppola’s retelling, Colin Farrell plays Cpl. John McBurney, an Irish mercenary who joined but has since deserted the Union army (a twist that allows Farrell to keep his native accent). Before he bleeds to death from a severe leg injury, McBurney is discovered in the woods by young Amy (Oona Laurence), who brings him back to the Miss Martha Farnsworth Seminary for Young Ladies, where she and six other women — including Miss Martha (Nicole Kidman) herself — are waiting out the war with French lessons and needlepoint.

Against their better judgment, the women, fascinated by the first man they’ve seen in ages, decide not to report his presence on their premises and opt instead to nurse him back to health. Bad idea, it turns out, but mostly for McBurney. A steamy hothouse atmosphere of lust and temptation leads to sudden violence, drastic action and fatal recriminations. Or, as Farrell succinctly summed up the plot at the post-screening press conference: “I have a penis. Treachery and hilarity ensue.”

Coppola isn’t a minimalist, exactly, but as in “Lost in Translation” and “Somewhere,” she demonstrates an economy of form and plot that tends to get mistaken for insubstantiality. More directors could learn something from her eye for the spare, telling detail, as well as her seeming allergy to narrative bloat. In “The Beguiled,” she once again practices the fine art of narrative subtraction, this time in service of an understated yet purposeful feminist reading.

Almost every subplot and contextual element in Siegel’s film — a spot of incest, a lone slave on the premises, an alarming visit by Confederate soldiers — has been neatly and not always satisfyingly pared away, leaving only the story’s battle-of-the-sexes core. Farrell’s McBurney is not permitted to reproduce any of Eastwood’s man-of-action heroics, and the women are given no motivations that would require them to cede the moral high ground.

I did miss some of the original movie’s psychosexual kinks, including Geraldine Page’s performance as an outwardly proper headmistress driven by her buried illicit desires. But this version of “The Beguiled” is rich in its own repressed feeling, and Coppola and her actors are at once fearless and commandingly precise as they nudge that hot-under-the-collar quality toward camp. Candlelit dinners, shot for maximum shadowy atmosphere by cinematographer Philippe Le Sourd, are invariably a source of knowing hilarity. “I hope you like apple pie!” winks Alicia (Elle Fanning), the most sexually forthright of the bunch.

The other key players here are Kirsten Dunst (who starred in Coppola’s “Marie Antoinette” and “The Virgin Suicides”), piercingly good as the naive young woman to whom McBurney pledges his love, and Kidman, whose scalpel-sharp performance seems to conceal tantalizing multitudes. In one of the movie’s most delicious scenes, Miss Martha bathes McBurney with a towel as he sleeps, her scrubbing motions becoming vaguer and more hesitant as her hand drifts below his waistline. The desire that flickers across Kidman’s stern countenance says it all: Maybe the South will rise again after all.

The roles and gender dynamics are almost completely reversed in “The Killing of a Sacred Deer,” the competition’s other film starring Colin Farrell and Nicole Kidman. The two play a well-to-do American couple, and whereas Kidman got creative with a hacksaw in “The Beguiled,” it’s Farrell who performs the surgical operations this time around. His character, Dr. Steven Murphy, is a cardiologist, which naturally means their sex life is dominated by medical role play. (When he says the words “general anesthetic,” she strips down and mimics being in a coma.)

Kinky sex, sharp objects, domestic weirdness: Welcome to the latest picture directed by the hellishly confrontational Greek satirist Yorgos Lanthimos, who competed at Cannes two years ago with “The Lobster.” That movie, which won the festival’s jury prize and went on to earn an Oscar nomination for its screenplay, was a surreal and haunting satire of monogamous love — governed by a rigid speculative premise but also open, in its way, to the rich and startlingly funny possibilities of human experience.

“The Killing of a Sacred Deer” is an infinitely nastier piece of work, and it seems to unfold in an entirely closed system, from which any trace of hope or redemption has been thoroughly expunged. Although Steven is happily married to Anna (Kidman), with whom he has two young children (Raffey Cassidy, Sunny Suljic), it’s clear from the moment he begins spending time with a disquietingly polite 16-year-old boy named Martin (Barry Keoghan) that their household will soon come under the gravest and strangest of threats.

Like Lanthimos’ 2009 art-house breakthrough, “Dogtooth,” still his finest and most sustained achievement, “The Killing of a Sacred Deer” offers a grimly funny reminder that home is where the horror is. It also subscribes to one of these festival’s dominant themes, evident also in Michael Haneke’s “Happy End” and Ruben Östlund’s “The Square”: the moral idiocy of a privileged, dishonest white man whose actions will inevitably take a toll on his young children.

Same message, wildly divergent executions. For about an hour I was held rapt by Keoghan, Kidman and Farrell (whose hangdog expressiveness Lanthimos seems to comprehend more fully than any other director), and by the loopiness of the dialogue — loopy in the sense that it’s both out there and repetitive. The filmmaking astonishes: From the Murphys’ menacingly cavernous suburban house to the glass-walled, high-ceilinged hospital compound where Steven works, no picture in competition this year has succeeded in using space, color and composition to fill the Grand Théâtre Lumière’s enormous screen quite this operatically.

“The Killing of a Sacred Deer” is sensationally well made, close to Kubrickian in its visual and sonic precision. It is also, to these eyes, an increasingly and dispiritingly empty provocation as it goes on. By the end of a tediously protracted second act that might as well be called “Slogtooth,” all suspense, hilarity and genuine horror have long since been drained away. As the bleakest, most uncompromising expression of an auteur’s vision, the result is pretty much pure, unfiltered Lanthimos — and in the future I think I’ll take him impure and filtered, thank you very much.

Cannes responds to the Manchester attacks with a moment of silence as two American indies shine: 'The Rider' and the thrillingly alive 'The Florida Project'

At 3 p.m. on Tuesday, the 70th Festival de Cannes observed a moment of silence in solidarity with the victims of Monday night’s terrorist attack at Manchester Arena. Earlier that morning, the festival had issued a press release expressing “its horror, anger and immense sadness.” The incident, the message continued, was “yet another attack on culture, youth and joyfulness, on our freedom, generosity and tolerance, all things that the Festival and those who make it possible — the artists, professionals and spectators — hold dear.”

With that statement came the implicit acknowledgment that such an attack could, of course, happen in Cannes. Not that anyone needed reminding, in light of the heightened security measures up and down the Croisette: the constant presence of armed police officers; the large, heavy planters lining the streets to protect against a vehicular attack, and the metal detectors set up at every entrance to the Palais des Festivals.

The festival had already weathered one false alarm on Friday, when a “suspicious object” that had been left behind in one of the screening rooms triggered a bomb scare. The Palais was evacuated, delaying by 45 minutes the first press screening of “Redoubtable,” Michel Hazanavicius’ flippant portrait of filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard. Twitter was quick to respond with nervous humor, including speculation that Godard had planted the object and obvious jokes along the lines of “the movie will be the real bomb.”

None of it was particularly funny at the time, and even less so now. Throughout the festival, attendees (myself included) could be heard complaining about the screening delays resulting from the metal detectors and extra-meticulous bag checks. Since Monday, though, I haven’t heard anyone complaining.

Tuesday was admittedly a quieter one than usual in Cannes — partly because of the sober circumstances, and partly because a number of journalists (myself included) opted to sleep in rather than attend the morning press screening of “Radiance,” the latest film from Japanese director Naomi Kawase. A fixture of the Cannes competition who won the 2007 Grand Prix for “The Mourning Forest,” Kawase is clearly beloved by the selection committee, but her films can test even the most hardened viewer’s appetite for contemplative lyricism and spiritual lugubriousness (and I have a high tolerance for both).

I hope to see “Radiance” on Sunday, when the festival will reprise all 19 films screening in this year’s competition. It’s an excellent opportunity to catch up with goodies you’ve missed and a fine excuse in the meantime to check out what’s playing elsewhere. The competition always dominates headlines at Cannes — especially this year’s edition, which conspicuously lacks any out-of-competition studio blockbusters like “Mad Max: Fury Road” in 2015 or “The BFG” last year — but with some luck and discernment, it almost always pays to venture down some of the festival’s less obvious avenues.

Come to this event often enough and you eventually learn the danger of making definitive pronouncements that you may regret months, weeks or even days later. So I’ll try to be as measured as I can when I say that I haven’t seen a more thrillingly alive movie at Cannes this year than “The Florida Project,” the latest tour de force of ramshackle realism from writer-director Sean Baker. It’s one of the highlights of Directors’ Fortnight, a parallel program that tends to be more hospitable to genre movies and American independents than the official selection. (The Fortnight is also screening “Patti Cake$,” one of the breakout titles at this year’s Sundance.)

Baker has risen to indie prominence over the years with his richly immersive low-budget portraits of marginalized communities, including “Prince of Broadway,” “Starlet” and his 2015 Sundance hit, “Tangerine.”

With its propulsive energy and terrific performances by a mostly nonprofessional cast, “The Florida Project” continues brilliantly in that vein. For two hours it plunges us into the life of a dumpy motel on the outskirts of Orlando, Fla., as seen largely through the eyes of one of its younger residents, an ebullient 6-year-old firecracker named Moonee (Brooklynn Prince, an astonishing discovery).

“Tangerine” had the novelty of being shot on a high-definition iPhone camera, in brilliant, retina-searing orange hues. For most of “The Florida Project,” Baker and his superb cinematographer Alexis Zabe (“Silent Light,” “Post Tenebras Lux”) have made the only slightly less exotic decision to shoot on 35-millimeter film — a choice that pays off in gloriously sun-streaked images that have life and movement forever spilling in and out of the frame.

The motel, a three-story purple colossus known as the Magic Inn, is a poor man’s Disney World located not too far from the real thing, a shelter for strugglers and stragglers with nowhere else to go. But as the camera chases Moonee and her friends up and down the stairs, watching them as they poke their heads where they don’t belong and make all manner of merry mischief, we come to see the motel as a place of hard-luck enchantment, a child’s wonderland with its own very real pleasures and perils.

The key to the movie is the way it balances that ebullient spirit with a tough, grown-up understanding of the crushing poverty and hopelessness that have brought Baker’s characters to this place.

Moonee, a good-hearted but severely neglected kid, is merely acting out the wild-child impulses of her ferociously unfit 22-year-old mother, Halley (Bria Vinaite), who must resort to increasingly desperate measures to pay her rent. A friend who disliked the film said that she kept wanting to slap the characters — an impulse that I’d say “The Florida Project” both invites and understands. Halley, in particular, is infuriating in her meanness and defiance, her hard edge never softening even when others try to help. Her rage against the world, no less than her survival instinct, is utterly without compromise.

The movie’s secret weapon is Bobby, the motel’s heart-of-gold manager who shows the patience of Job as he bails out his tenants again and again, none more frequently or fruitlessly than Halley. Bobby is played by Willem Dafoe in the sort of performance so unforced and lived-in, so grounded in workaday tenderness, that it makes you fall in love with an actor anew. By the end of “The Florida Project,” which leaves the tension between hardscrabble realism and hopeful fantasy shatteringly unresolved, we have come to see this tragedy through his eyes too.

If Baker’s movie gave Cannes audiences a bracing dose of lower-depths claustrophobia and sensory overload, Directors’ Fortnight audiences could find an achingly beautiful counterweight in the wide-open plains and long, enveloping silences of “The Rider.” Gorgeously directed by Chloé Zhao with the same assured command of documentary and narrative techniques she showed in her 2015 debut, “Songs My Brothers Taught Me,” this is a lovely, lyrical ode to South Dakota rodeo culture, centered around a Sioux cowboy named Brady Blackburn who, having suffered a severe head injury, is struggling with the likelihood that he’ll never ride again.

Brady is played by 20-year-old Brady Jandreau, an utterly magnetic screen presence who turns out to be starring in a loosely fictionalized version of his own story. (His father and younger sister similarly play versions of themselves on-screen.) As it follows Brady down his hard road to recovery, studying him as he literally gets back on his horse and weighs his dreams against his survival, “The Rider” becomes both a classically absorbing western and a wounding close-up of masculinity in crisis.

Zhao’s film was acquired for distribution by Sony Pictures Classics (which also nabbed another of the festival’s strongest films, Andrei Zvyagintsev’s “Loveless”), which should help it find the broader audience it deserves. Still, it was a pleasure to discover it in Cannes, with its eternal promise of cinema without borders. Both “The Rider” and “The Florida Project” draw us into worlds that few of us have known, and whose inhabitants have known little else. They are also a welcome reminder that sometimes you can fly halfway around the world and learn something indelible and true about the country you left behind.

The dysfunctional households of ‘Happy End’ and ‘The Meyerowitz Stories’

No one slits his own throat, shoots a child to death or sniffs a soiled tissue in “Happy End,” Michael Haneke’s latest attack on the discreet harm of the bourgeoisie. There is a suspicious death, to be sure, as well as a grim accident and a few off-screen suicide attempts. But for nearly all 107 minutes of this formally immaculate, perversely unruffled portrait of a very wealthy French family, Haneke seems to go out of his way to avoid the brutal shock tactics of “Funny Games” and “The Piano Teacher,” evincing the kind of artful restraint that may initially remind you of his crowning achievement, “Amour.”

That 2012 film, which earned the Austrian master his second Palme d’Or at Cannes (the first was for 2009’s “The White Ribbon”) as well as the Oscar for best foreign-language film, told the story of an elderly couple confronting the abyss. It was so direct and sincere in its devastation that it won over even those who had previously loathed the filmmaker and his exquisite brand of cinematic sadism. We were seeing a new Haneke, the raves declared, a more mature, tender Haneke, still as rigorously unsentimental as ever, but perhaps more of a humanist at heart than he had led us to believe.

The joke is clearly on us (again!). “Happy End,” Haneke’s eighth picture to premiere in competition at Cannes, suggests that either “Amour” was a calculated fluke, meant to lull us into a false sense of trust, or that the line between cruelty and compassion is never as clear as we’d like to think. Watching the movie is like sitting in a room where not much happens calmly and politely for almost two hours, until you realize the place has been slowly filling with poison gas and Haneke has spent the entire time quietly putting chains on the doors.

Jean-Louis Trintignant and Isabelle Huppert play father and daughter — the elderly Georges Laurent and middle-aged Anne — resuming their on-screen relationship if not their exact characters from “Amour.” (It’s more than implied that this movie is an indirect sequel.) They run a construction company and live in a large estate in the French city of Calais, along with Anne’s black-sheep son, Pierre (Franz Rogowski); her doctor brother, Thomas (Mathieu Kassovitz); and Thomas’ second wife, Anaïs (Laura Verlinden). The newest member of the household is Ève (Fantine Harduin), Thomas’ 12-year-old daughter from his first marriage, who has come to live with the Laurents while her mother is in the hospital after having been mysteriously poisoned.

Throughout the picture, Haneke sows seeds of dread and disaster, but always uproots them before they can blossom into full-on horror — and as always, that reprieve feels like the very opposite of mercy. The movie is a slippery, serpentine thing; a single cut can propel the plot forward by days or weeks, but the overall progress feels disquietingly circular.

“Happy End” plays at times like a critique of technological alienation, dispensing key plot twists via chilling iPhone videos and Facebook chat sessions. Then it morphs into a smirking bad-seed thriller, with Harduin superb as the seriously disturbed Ève, her limited repertoire of blank stares cutting to the bone.

Initial word had suggested that “Happy End” would be Haneke’s statement on the global refugee crisis, and so it is. But in the film’s most telling stroke, most of the migrants we see — including Rachid (Hassam Ghancy) and Jamila (Nabiha Akkari), the hard-working, painfully well-mannered Moroccan immigrant couple who serve the household — are, for the most part, as invisible to us as they are to the Laurents. The TV blares horrible tidings from around the world, but it must compete more than ever with the characters’ attachment to their own personal screens.

Unlike, say, the bourgeois couple in “Caché,” who were at least capable of feeling guilty for their complicity in the repression of the French Algerian population, the Laurents will not be called to account for their crimes against humanity, or even to acknowledge them. If Haneke avoids obvious jolts and payoffs here, it may very well be because he sees his characters — and by extension, his viewers — as well beyond the reach of shock, guilt or redemption. (And if a parable about the devastation wrought by a morally oblivious, obscenely privileged family carries an unmistakable Trumpian echo, let it never be said that Haneke’s contempt is restricted to one side of the Atlantic.)

The film ripples with so many echoes of so many of the director’s past work that at times it verges on self-parody. Besides “Amour” and “Caché,” the movie seems to deliberately evoke the technological horror of “Benny’s Video,” the children-are-evil-incarnate vibe of “The White Ribbon,” and the interlocking narrative threads of the brilliant “Code Unknown.” The title “Happy End” could refer to any number of things: a mercy killing that never comes, the death of the European experiment as we know it, or the end of Haneke’s career itself.

That’s a prospect that many audiences, in Cannes and beyond, would no doubt applaud. Love or loathe this glib, impossible, queasily hilarious and thoroughly terrifying movie, one thing is all but certain: You will give Michael Haneke exactly the reaction he wanted.

‘The Meyerowitz Stories’’ buried resentments

Sometimes those Cannes schedulers have a devilish sense of humor, to judge by the screening of “Happy End” on the same day as a rather more approachable dysfunctional-family movie, “The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected).”

Noah Baumbach’s latest is a warm and appealingly shaggy comedy about a New York Jewish family brought back together by the usual winds of change — separation, graduation, illness. Dustin Hoffman plays the overbearing, much-married Meyerowitz paterfamilias, Harold, a little-known sculptor who both bemoans and relishes his status as the sole working artist of the bunch.

Presently married to Maureen (Emma Thompson, loopier than she’s ever been since playing Professor Trelawney at Hogwarts), Harold has three children from his prior marriages. Adam Sandler, in one of those once-in-a-blue-moon reminders of what a terrific actor he can be, plays the genial elder son, Danny, who feels perpetually overshadowed by his younger half-brother, Matthew (Ben Stiller), a successful businessman who makes very rare visits from his home in Los Angeles.

Also in the mix is Danny’s stalwart sister, Jean (a wonderful Elizabeth Marvel), who suffers her dad’s neglect in agreeable silence, and whom the movie somewhat frustratingly sidelines in favor of all the father-son Sturm und Drang. Some more focus on the Meyerowitz women overall would not have gone awry: Candice Bergen makes a brief, memorable appearance as Matthew’s mother, while Grace Van Patten gets the most attention as Danny’s college-bound daughter, Eliza, an aspiring filmmaker with an apparent taste for Troma.

Hoffman is often marvelously insufferable as Harold, whose stubbornness and artistic pomposity make him a spiritual cousin to Bernard Berkman, the novelist played by Jeff Daniels in Baumbach’s “The Squid and the Whale.” Like that film and Wes Anderson’s “The Royal Tenenbaums,” “The Meyerowitz Stories” is very much about the burden of having a difficult dad, although toward the end I could have sworn the movie also morphed into a screwball remake of “Summer Hours,” Olivier Assayas’ wonderful 2009 film about three siblings trying to figure out how to deal with an artistic inheritance.

None of this — the buried resentments, the hesitant stabs at reconciliation — is unfamiliar, but it’s funny and affecting all the same. Individually and together, the members of this family forge their own sweet, resilient music — quite literally when it comes to Randy Newman’s lovely score. When Danny and Eliza perform one song as a duet, with Sandler gently tickling the ivories, “The Meyerowitz Stories” becomes awfully hard to resist — and tempting to reimagine as a full-blown musical.

The engrossing sprawl of ‘The Square’ and ‘120 Beats Per Minute,’ or how I survived the two longest films in the Palme d'Or race

Maybe it was inevitable that Ruben Östlund would get around to skewering the pretensions of the modern art world, even at the risk of indicting his own tableau-like aesthetics. In films like “Play” and his 2014 Cannes sensation “Force Majeure,” this exacting Swedish auteur positions his characters in beautifully lit, immaculately framed compositions that solicit our scrutiny, our empathetic laughter and, at times, our withering contempt.

“The Square,” Östlund’s rich, expansive and often savagely funny new film, begins as a sharp sendup of the goings-on at a contemporary art museum. Several of the pieces on display come in for easy laughs — check out the room full of perfectly arranged, identical-looking rock piles, or not — but the real exhibition here is the museum’s curator, Christian (Danish actor Claes Bang), a divorced father of two girls and a proud, prominent member of his city’s cultural elite.

As in “Force Majeure,” a single lapse in judgment can cause a man’s entire life to unravel. In this case, however, the lapse is rather more premeditated. When Christian is mugged in broad daylight and traces his stolen phone and wallet to an apartment building in a rough neighborhood, he undertakes a reckless course of action that lays bare the hollowness beneath his enlightened liberal veneer. But Östlund’s moral indictment comes at Christian from all angles, and always in ways that rebound uncomfortably on the viewer.

An ill-advised one-night stand with an American journalist (Elisabeth Moss, a long way from “The Handmaid’s Tale”) leads to a long, barbed exchange about men, women and the abuses and seductions of power. In the interests of starting a provocative conversation, Christian’s team devises a disastrous video ad for the museum, and amid the ensuing controversy, the movie takes care to mock the outrage police and the free-speech advocates with equal intensity. The film may single out Christian for criticism, but it ultimately sees him as representative of an entire rotten society that prides itself on its humanist and progressive values, but always avoids the risk of actual empathy, let alone accountability.

That critique comes to the fore in a brilliant, Buñuelian performance-art sequence that will lodge itself in your brain for days, built around a terrifying turn by Terry Notary, whose animal/creature motion-capture work you may have seen in “Kong: Skull Island” and the recent “Planet of the Apes” movies.

For all its immaculate polish, “The Square” turns out to be not a tidy exercise in clinical detachment but a ferocious drama of conscience. And for all the scorn it heaps upon Christian’s rarefied milieu, it’s entirely sincere in its acknowledgment that art — this movie itself being a thorny and fascinating example — can tell us things about ourselves we’d rather not know.

Running just shy of 2½ hours, “The Square” is one of the two longest features in competition at Cannes this year, the other one being Robin Campillo’s 143-minute “120 Beats Per Minute (120 Battements Par Minute)”, which screened for the press on Saturday morning. Neither one will prove a taxing experience for a Cannes veteran who has endured the marathon running times of, say, Nuri Bilge Ceylan, whose 196-minute cinematic glacier “Winter Sleep” won the Palme d’Or in 2014 (deservedly, in my opinion, though there are some who maintain the film simply exhausted the jury into submission).

The Östlund and Campillo films were a breeze by comparison. Even still, journalists filing out of both screenings could be heard grumbling their usual variations on “It’s a little too long” and “It could do with a trim” — I know, because in at least one case, I was one of the grumblers. But at the risk of contradicting myself or reversing my opinion (something that never, ever happens in Cannes!), I’d also suggest that concision can be overrated, and tedium is entirely in the eye of the beholder.

A loose-limbed, exploratory approach can make all the sense in the world when a filmmaker is attempting to grapple with not just a character but an entire milieu, as Östlund does in “The Square,” or trying to capture both the essence and the specifics of an unruly activist movement, as Campillo does in “120 Beats Per Minute.”

An impassioned and deeply absorbing look back at the French AIDS crisis during the early ’90s, Campillo’s third feature (after “They Came Back” and “Eastern Boys”) follows several members of the Paris-based wing of ACT UP as they meet, argue, strategize and regularly make themselves heard in the most confrontational way possible. But talk must go hand-in-hand with action, and we follow the activists as they march in gay pride parades, hand out condoms in classrooms and even take a Big Pharma firm by storm, going so far as to vandalize the premises with fake blood.

If “120 Beats Per Minute” is inescapably a period piece, a flashback to a moment when AIDS was decimating the gay community in much higher numbers than it is today, the movie nevertheless unfolds in a brisk, urgent present tense that refuses the consolations of nostalgia. Campillo has co-written several screenplays with his fellow French director Laurent Cantet, most notably their marvelous 2008 Palme winner, “The Class.” That film’s sensibility, its feel for the exuberant language and overlapping rhythms of group discussion, is very much in evidence here.

The political is personal and vice versa, and in time all that vigorous back-and-forth gives rise to a love story between the outspoken, HIV-positive Sean (Nahuel Pérez Biscayart, superb) and the more reserved, HIV-negative Nathan (Arnaud Valois). If the near-constant shadow of illness and death gives these characters’ activism its unusual urgency, it also has the effect of hastening their intimacy, but deepening it as well. In an extended love scene notable for both its hot-blooded sensuality and its intricate, bittersweet play with memory, “120 Beats Per Minute” embraces sex as not just an expression of love or lust, but something more — an act of life-sustaining defiance. For these young men with nothing left to lose, it’s the ultimate way of giving death the finger.

The festival may still be in its early days, but some have already tipped “120 Beats Per Minute” to win a prize from this year’s Pedro Almodóvar-headed competition jury. Quite apart from its arrival at a genuine watershed moment for LGBT cinema, it’s the sort of film that connects robustly and unambiguously with the audience on an emotional level — a virtue that has been known to win over juries over the past.

Some may quibble that the movie goes on about 10 minutes longer than it has to, squandering a perfectly haunting final shot along the way. (You’ll know it when you see it.) But Campillo, a filmmaker riveted by strategic minutiae, makes you understand the logic behind his methods. Our tears, he seems to be saying, shouldn’t blind us to the necessity of fighting and resisting with every last breath.

Cinematic riches and screening glitches: Bong Joon-ho's 'Okja' makes a bumpy but thrilling landing on the Croisette

Isolated technical snafus are nothing new at the Cannes Film Festival. Two years ago, those of us at the first press screening of Jia Zhangke’s “Mountains May Depart” waited patiently as the opening scenes were replayed a few times, due to bizarre image distortions. In 2006, the morning showing of Alejandro Gonzalez Iñárritu’s “Babel” ground to a halt for several minutes due to a reel mix-up — a problem that would almost certainly never arise now, when nearly everything at Cannes is shot and projected digitally.

Non-celluloid technology, of course, comes with its own potential for error, often accompanied by a healthy dose of schadenfreude from cinema traditionalists. Those who have objected to Netflix’s presence at the most prestigious party in world cinema were probably delighted by the technical issues that befell the Friday-morning screening of Bong Joon-ho’s “Okja,” which was initially projected with portions of the frame cut off. The gaffe caused a lengthy delay and drew contemptuous jeers from the press audience, though admittedly, some had been booing from the moment the Netflix logo appeared.

Just as the screening came to an end, Cannes claimed responsibility for the incident and issued an apology to the filmmakers and the audience. Even still, it was an inauspicious beginning for Netflix’s big 2017 Croisette coming-out party, and it felt like the culmination of several weeks’ worth of industry tension after the announcement that two of the distributor’s titles, “Okja” and Noah Baumbach’s “The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected),” had been chosen for the competition.

Shortly before the festival began, Cannes issued a release noting that 2017 would be the first and last year that streaming-only films would be allowed to enter the competition. All Palme contenders henceforth will be required to screen in French cinemas — a tough condition for Netflix to meet, given France’s strictly enforced 36-month theatrical window. (For what it’s worth, “Okja” will receive theatrical release in 190 countries on June 28, the same day it becomes available for worldwide streaming on Netflix.)

So, how’s the movie? Too good for all this controversy, frankly. Although “Okja” features a large international cast headed by Tilda Swinton (much like Bong’s recent “Snowpiercer”), its disarming blend of corporate satire, environmental cautionary tale and girl-centric creature feature suggests a throwback of sorts to the director’s 2006 smash hit, “The Host.” But unlike that film’s hideous, child-napping Han River dweller, Okja couldn’t be cuter or friendlier: She is one of a new breed of genetically modified “super-pigs,” with which the fictional Mirando Corporation hopes to rejuvenate and dominate the global pork market — though not if a young South Korean girl named Mija (the terrific Ahn Seo-hyun), Okja’s caretaker and best friend, has anything to say about it.

The movie’s first half is pure chase-thriller bliss, as Mija tries to rescue Okja from being sliced into pork belly — a quest in which she is both helped and hindered by a crack team of friendly animal-rights activists. (The merry bunch features Paul Dano as its warm, principled leader, plus Steven Yeun, Lily Collins, Daniel Henshall and Devon Bostick.) On the other side of the moral-political spectrum is Swinton as the monstrously insecure head of Mirando, though in the scenery-chewing sweepstakes, she gets some real competition from a rattled, over-the-top Jake Gyllenhaal as the company’s public face.

But it’s the 13-year-old Ahn who holds this pig-screen entertainment together as it (ahem) barrels forward into its darker, tonally trickier second half, en route to a devastating finale that may wreak havoc on your bacon consumption. As Mija singlehandedly stares down the greedy multinational enterprise that threatens to separate her from her beloved super-sow, her determination lends this weird, funny, and disturbing speculative fairy tale a striking degree of emotional force.

All in all, it’s the kind of experience that truly does warrant the pictorial immensity that only a darkened theater can provide, and I say that as someone who has been fortunate enough to see most of Bong’s work projected on the big screen. “The Host” was the single finest film I saw at Cannes in 2006, never mind that it was playing in the Directors’ Fortnight, not the competition. His 2009 thriller, “Mother,” had to settle for a slot in the official selection’s Un Certain Regard sidebar, which didn’t stop it from drawing some of the festival’s biggest raves.

Now the director has made his long-overdue first appearance in the main program, and with a picture that juggles genres, ideas, visual effects and politics with his characteristic aplomb. There will likely be no easy end to the debate over whether Netflix belongs in competition at Cannes, but there can be no doubt that Bong Joon-ho does.

‘Jupiter’s Moon’ tries to fly

This year’s competition has so far proven refreshingly elastic in terms of genre, judging by the inclusion of a satirical sci-fi action movie like “Okja” and a family-friendly adventure story like Todd Haynes’ “Wonderstruck.” An altogether more divisive example arrived Thursday in the form of “Jupiter’s Moon,” a virtuosic muddle of a thriller from the Hungarian director Kornél Mundruczó, in which a slain Syrian refugee named Aryan (played by Zsombor Jéger) is resurrected as an unambiguous Christ figure equipped with bizarre supernatural powers.

Previously in competition with “Delta” (2008) and “Tender Son: The Frankenstein Project” (2010), Mundruczó won the festival’s Un Certain Regard prize in 2014 with “White God,” a sensational thriller about a canine uprising that provided a handy metaphor for the return of the repressed. A similar fusion of B-movie jolts and topical allegory, “Jupiter’s Moon” is clearly an attack on modern society’s inhumane response to the global refugee crisis. It is also a rebuke to the venality of its protagonist, Stern (Merab Ninidze), a troubled doctor who initially sees Aryan as fodder for a get-rich-quick scheme.

But finally, and most wearyingly, the movie is an earnest religious parable, executed with a leadenness that can feel at odds with Aryan’s gravity-defying new abilities. The moments you remember are the flashiest: Aryan making a room spin in “Inception”-style circles or levitating over a city street, like a melancholy homage to “The Matrix” and “Wings of Desire” in one. In these moments your eyes pop out of your head, but at other points they might be more inclined to roll.

Vanessa Redgrave, first-time director

Tackling the global refugee crisis in more straightforward fashion is “Sea Sorrow,” a 74-minute documentary, screening out of competition, that marks the directorial debut of Vanessa Redgrave. Clunky though not uninteresting in its assembly, and admirably direct in its anger and passion, the film features interviews with migrants from Syria, Afghanistan, Guinea and elsewhere, as well as direct-to-camera narration from Redgrave, who speaks of everything from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights to her own refugee status as a child forced to flee London during World War II.

“Sea Sorrow” features an excerpt from Shakespeare’s “The Tempest” performed by Ralph Fiennes and Daisy Bevan, a touch that risks pretension in a genuine bid for empathy. The stirring result is the very definition of a film with its heart in the right place, even when its art isn’t.

On a day of unceasing news alerts, the vital optimism of ‘Wonderstruck’ and ‘Let the Sunshine In’

Sometimes a film festival holds up a mirror to the world’s harshest realities, and sometimes it provides a welcome respite from them.

On Thursday, amid what felt like an unceasing wave of news alerts from the U.S. — the sudden deaths of Roger Ailes and Chris Cornell, a fatal car crash in Times Square, the latest developments in the Trump/Russia saga — the Cannes Film Festival saw fit to unveil two pictures notable for their exquisite loveliness, their enchanting good vibes, and their sweet yet tough-minded suggestion that everything might turn out just fine in the end.

Needless to say, neither of the films in question was directed by Michael Haneke, even if his latest picture does bear the (presumably ironic) title “Happy End.” (It will screen for the press on Sunday.) Instead, festivalgoers queued up amid heightened security for the first screenings of Todd Haynes’ “Wonderstruck,” which premiered in the main competition, and Claire Denis’ “Let the Sunshine In” (“Un Beau Soleil Intérieur”), which opened the parallel Directors’ Fortnight sidebar.

Their equally optimistic titles aside, both movies found their respective auteurs shrewdly staking out fresh dramatic territory, and potentially even courting a new audience. Haynes, rightly celebrated as a brilliant anatomist of Eisenhower-era repression (“Far From Heaven,” “Carol”), puts a kid-friendly spin on his usual themes of isolation and frustrated longing in “Wonderstruck,” an ingenious and often captivating adaptation of Brian Selznick’s 2011 children’s novel.

The film cross-cuts relentlessly between two children living in two different eras. In 1977, the recently orphaned Ben (Oakes Fegley) runs away from his hometown of Gunflint, Minn., and sets out for New York. Fifty years earlier, in a parallel thread shot entirely in black-and-white, the sadly neglected Rose (a wonderful Millicent Simmonds) leaves Hoboken, N.J., and plots her own course to the Big Apple.

Haynes is characteristically sensitive in his treatment of the fact that Ben and Rose are both deaf, a crucial plot point that complicates their adventures and underlines their outsider status. It also affords Haynes another opportunity to reveal his mastery of intricate mise-en-scène: Much of “Wonderstruck” plays like a silent film, with Carter Burwell’s lilting, surging score filling in the occasional long pauses between audible dialogue. (The 1927 thread incorporates footage from a faux silent film starring a bewigged Julianne Moore, reaffirming herself as Haynes’ most reliable muse.)

What unites Ben and Rose, apart from their deafness, is revealed in skillfully heart-tugging fashion against a rich, sweeping panorama of pre- and post-Depression New York street life. The prominent role played by various New York museums reminded me, at times, of E.L. Konigsburg’s novel “From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler.” At other times the movie struck me as a watchable version of “Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close,” a 9/11 grief-porn abomination that similarly turned on a child’s solo quest through the streets of New York.

Selznick, who adapted his own book, also wrote the novel that inspired Martin Scorsese’s whirligig kiddie epic “Hugo,” which harnessed childlike wonderment and 3-D technology in service of an impassioned brief on the necessity of film preservation. To these eyes, “Wonderstruck” is a stronger film and an equally intricate narrative construct — the rare all-ages movie that illuminates the inner lives of children with warmth, intelligence and nary a hint of condescension.

The weave so impressive, it feels almost quibblesome to note that it doesn’t always hold together. The cleverly bifurcated narrative must have been murder to assemble in the editing room, and the midsection can’t help but sag under the weight of the various temporal shifts and visual echoes. At times, “Wonderstruck” feels less like storytelling than scaffolding; there’s a bit more on-the-surface busyness than its simple, touching tale can fully support.

But even that flaw bespeaks an uncommon level of ambition. This big-hearted movie reaches for the stars, and it’s more than OK that its reach exceeds its grasp.

The French filmmaker Claire Denis has earned a world-class reputation for her oblique narrative style, her richly sensual filmmaking and her fascination with the legacy of French colonialism and the African diaspora. To see a film like “Beau Travail” or “White Material,” or her magnificent 2005 head-scratcher “The Intruder,” is to behold an almost terrifying level of aesthetic accomplishment. Depending on the title and your level of preparation, you may walk out of the theater feeling intoxicated, ravished and not a little bit baffled.

With “Let the Sunshine In,” Denis has made something almost as rare as a family-friendly Cannes movie: an exquisite romantic dramedy that, for all its surface accessibility, ultimately demands (and rewards) as much wide-awake attention as any of her previous pictures. In his Variety review, the critic Guy Lodge described it as “a parallel-universe Nancy Meyers movie,” an unimprovable formulation that captures both the film’s droll wit and the essential seriousness with which it handles an often-derided “women’s picture” sub-genre.

Juliette Binoche stars as Isabelle, a Parisian artist, mother and divorcee whom we first see having passionate sex with a banker (Xavier Beauvois). The episode of coitus interruptus that follows sets a wry pattern for all of Isabelle’s interactions with her many suitors (played by Nicolas Duvauchelle, Bruno Podalydès and others), in which the thrill of initial interest soon gives way to hesitation, disappointment and lacerating self-critique.

Language and its innumerable pitfalls are a rich and endless source of comic anxiety. Flirtation is constantly mistaken for rejection. If the typical Hollywood romantic comedy thrives on canned pronouncements and easy one-liners, “Let the Sunshine In” is very much a movie about people struggling aloud to find the right words to express their feelings, and failing magnificently. (The film was inspired by Roland Barthes’ “Fragments: A Lovers’ Discourse,” and written by Denis in collaboration with the novelist Christine Angot.)

Binoche has gone from strength to strength in recent years; still, if she has ever been more radiant or effortlessly expressive on screen than she is here, the example is not immediately coming to mind. And Denis, whose narratives can be daringly free-associative, has structured “Let the Sunshine In” elegantly and intuitively, as a series of richly human encounters that flow, meander and pulse with life. It’s an exquisite movie — and one that, on a day of unusually grim tidings beyond the Cannes bubble, had the good grace to live up to its title.

Frothy ‘Ghosts’ and ‘Loveless’ despair: On opening night, red carpet poses and two directors’ divergent views on marriage

Opening night has long been a tricky proposition at the Cannes Film Festival. It’s a high-profile slot, to be sure, but one that confers an oddly weightless, even ersatz prestige.

There have been some charming exceptions to the rule, Pixar’s “Up” (2009) and Wes Anderson’s “Moonrise Kingdom” (2012) not least among them. But for the most part, the festival seems to go out of its way to select a film that won’t upstage the star-packed, auteur-heavy main program, even if it’s a film that few Cannes attendees will even remember in a few days’ time.

That amnesia tends to set in whether the opener is a gaudy summer blockbuster like Baz Luhrmann’s “The Great Gatsby,” which provided the 2013 festival with an especially lavish kickoff, or a slice of low-budget French social realism like Emmanuelle Bercot’s “Standing Tall” (2014). Still, better indifference than the instant notoriety that greeted Ron Howard’s “The Da Vinci Code” back in 2006, when it was promptly (and rightly) declared an opening-night stinker for the ages.

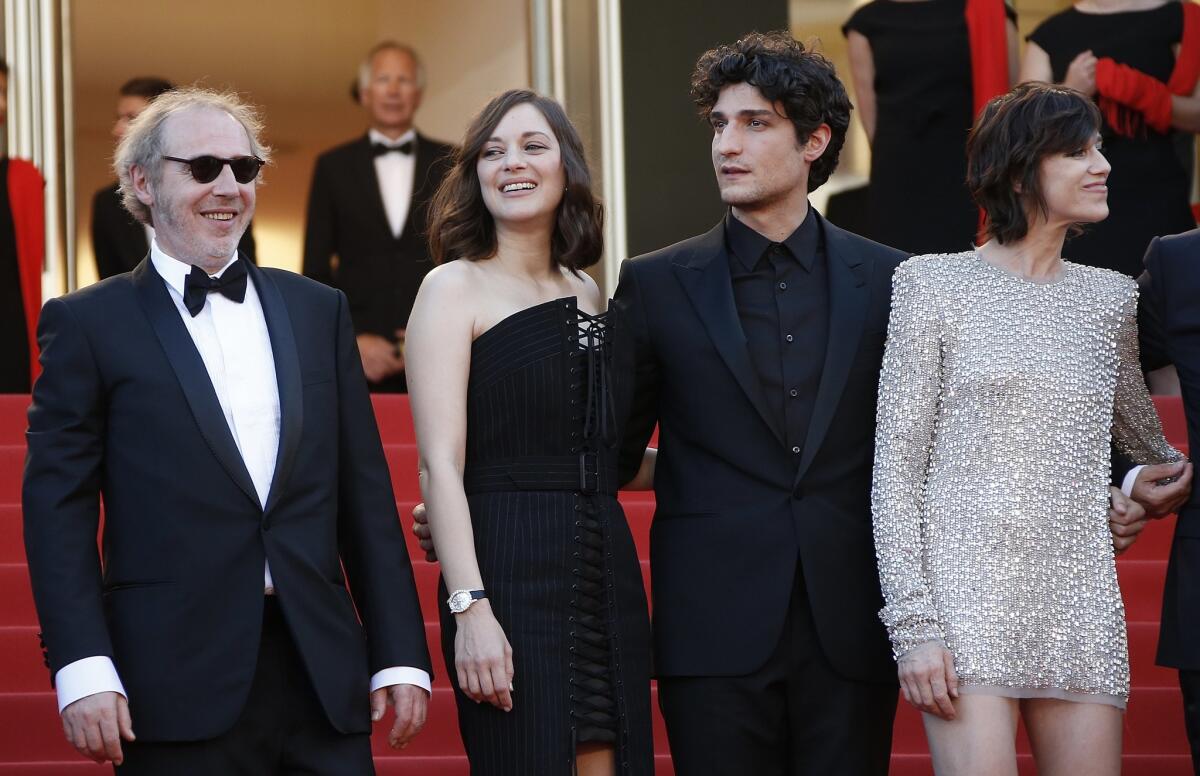

No such hostility awaits this year’s 70th anniversary opener, Arnaud Desplechin’s “Ismael’s Ghosts,” though I suspect not much enthusiasm or visibility is in store, either. Desplechin is one of the pre-eminent French filmmakers of his generation, and his best work, which includes “My Sex Life … or How I Got Into an Argument,” “Kings and Queen” and “A Christmas Tale,” has the power to make directorial indulgence seem like a virtue.

“Ismael’s Ghosts,” by contrast, is the rare Desplechin joint that seems to want for discipline, which perhaps makes it entirely fitting that it’s about an undisciplined filmmaker. That would be Ismael Vuillard (Mathieu Amalric), a genial, shambling man of cinema who’s on a beachside retreat with his astrophysicist girlfriend, Sylvia (Charlotte Gainsbourg), when the two are suddenly paid a visit by his wife, Carlotta (Marion Cotillard), who vanished mysteriously 21 years earlier.

It’s the sort of premise that could easily be played for plate-smashing histrionics or delirious romantic farce, and there are shades of both. Desplechin’s movies are often praised for their wonderfully lived-in messiness, and for a while “Ismael’s Ghosts” seems to fit that inspired pattern. It’s a busy, convulsive and fragmentary piece of work, with strange plot turns and dazzling formal gimmicks (iris shots, intra-scene dissolves, weirdly unmotivated music cues) coming at you every minute.

But then the thing derails and becomes, shall we say, the wrong kind of mess. Scenes from Ismael’s latest production, a thriller about a genial spy named Ivan Dedalus (Louis Garrel), pepper the main narrative in cheeky film-within-a-film fashion. Art begins to mirror life (or is it vice versa?), and Desplechin’s elaborate meta-conceits take a bizarre and abruptly violent turn.

More fatally, the romantic triangle at the movie’s center never becomes sufficiently engaging to warrant all this fussy ornamentation. Amalric has starred in six previous Desplechin joints, but rarely has he been encouraged to go as shoutily over the top as he does here. Cotillard’s character seems lost in a narcissistic fog, oblivious to the hell she has inflicted on her husband and her father (a touching Laszlo Szabo). The saving grace is Gainsbourg, whose initial hard-to-get rapport with Amalric — no one can do wistful exasperation quite like Gainsbourg — is one of the movie’s undiluted pleasures.

When I interviewed Desplechin two years ago, he described the still-in-the-works “Ismael’s Ghosts” as “full of bitterness and anger and furious characters … the shape and form of it are quite different from anything I’ve ever done.”

At the time, he was preparing for the U.S. release of his superb prior picture, “My Golden Days,” which had been mystifyingly denied a competition slot at Cannes in 2014 and wound up premiering in the parallel Directors’ Fortnight program instead.

Desplechin, who served on the Cannes competition jury last year, is now officially back in the official selection with “Ismael’s Ghosts,” even though the film, like most Cannes opening-night films, is playing out of competition. That seems about right. Not unlike this year’s jury president, Pedro Almodóvar, Desplechin is a perennial Cannes bridesmaid who has yet to win the Palme d’Or. I suspect he will someday, and for a movie that haunts my dreams longer than these particular “Ghosts” will.

As Amalric, Cotillard, Gainsbourg and Garrel posed on the red carpet outside the festival’s Grand Théâtre Lumière on Wednesday evening, a bevy of jet-lagged journalists made their way into the nearby Salle Debussy for their opening-night attraction: the first press screening of the competition. And in typically shrewd fashion, festival programmers saw fit to counter the antic frothiness of “Ismael’s Ghosts” with “Loveless,” two hours of gorgeously gloomy existential despair courtesy of the well-regarded Russian filmmaker Andrey Zvyagintsev.

Often touted as an heir to Tarkovsky, Russian cinema’s other famously austere Andrey, Zvyagintsev previously competed at Cannes with “Leviathan” (2014), which won the jury’s screenwriting award and went on to score an Oscar nomination for foreign-language film. Like that earlier film, “Loveless” is a shatteringly bleak family drama that expands into a corrosive critique of its country’s social, political and spiritual ills.

The setup may remind you, on paper, of Asghar Farhadi’s “A Separation”: An unhappy marriage is at an end, leaving a child’s fate hanging in the balance. But “Loveless” has none of Farhadi’s delicate humanist probing. Its bitterly feuding spouses, Zhenya (Maryana Spivak) and Boris (Alexei Rozin), are irredeemably rotten from the get-go. Eager to move on with their new romantic partners (Boris’ lover is pregnant as the divorce proceedings get under way), they prove largely indifferent to the suffering of their son, Alyosha (Matvey Novikov, in a near-silent scream of a performance), the product of an unwanted pregnancy that forced them to marry 12 years earlier.

One day Alyosha goes missing, prompting a police investigation, an extensive search and some parental anguish (though not nearly enough). If the first half’s acerbic “Scenes From a Marriage” approach feels a touch familiar, the procedural minutiae of the second half proves almost inexplicably mesmerizing. A shot of workers moving through a derelict building, or even the simple sight of orange-vested volunteers moving in a line across the rugged terrain, attains the full majestic force of Zvyagintsev’s remarkable visual concentration. (His cinematographer is Mikhail Krichman, who also shot “Leviathan” and the director’s underrated 2007 drama, “The Banishment.”)

Moments like these — much like the shots of the couple’s glass-walled apartment, subtly pointing to the class dynamics at work — can make you feel as if you’re staring at an X-ray of the sick soul of modern Russia. That may be an overly reductive reading, but it’s one that suits the unapologetic bluntness of Zvyagintsev’s political jabs. TVs and radios are forever supplying a background stream of grim headlines, the most recent of which concerns the conflict in Eastern Ukraine.

Russia has of course been dominating the American news cycle for reasons that are never mentioned here, and for those inclined to dismiss an entire country as a sinister monolithic entity, this picture’s rich artistry and slow-burning moral anger will serve as an important corrective. It scarcely needs to be stated that the lessons of “Loveless” are not limited to the Russian populace alone. By the end of this despairingly sad movie, Zvyagintsev forces us to ask what kind of world we’re leaving behind for our children, and whether we can ever love them enough to make up the difference.

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.