‘What can cinema do?’ Travel ban puts Oscar nominees for foreign-language film in the spotlight

In many ways, the foreign-language film category has always embodied the contradictory passions that surround the Oscars themselves — it’s wildly important to some, utterly meaningless to others and a vague sidebar to many.

This year that role has become even more pointed. In an awards season already marked by political acceptance speeches and red carpet interviews, the foreign-language nominees find themselves in an unexpected and very particular spotlight.

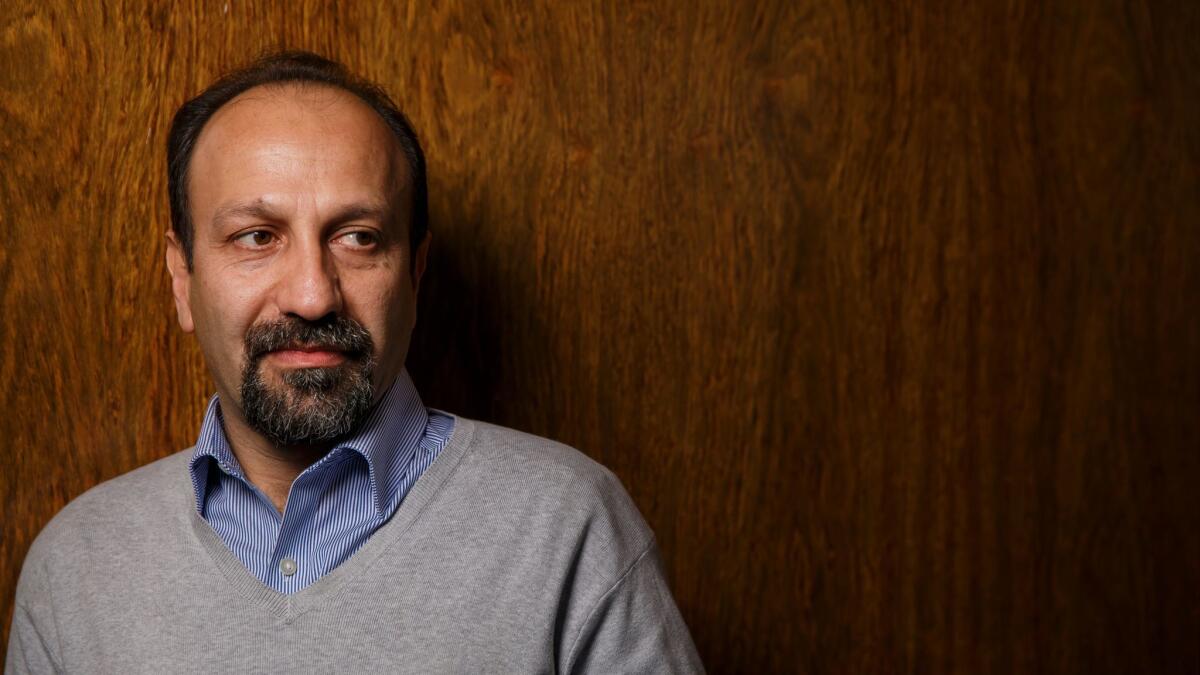

Shortly after President Trump’s seven-country travel ban was announced Jan. 27, the fate of Iranian filmmaker Asghar Farhadi, nominated for “The Salesman,” became the subject of frenzied speculation. Within a few days, Farhadi released a statement saying he had decided to stay home in protest of “the unjust circumstances” of the order, even as “I know that many in the American film industry and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Science are opposed to the fanaticism and extremism which are today taking place more than ever.” He has maintained this position even after the suspension of the ban.

Suddenly a vote for “The Salesman,” a deeply felt drama of marriage, moral struggle and compromise, also became a potential act of protest. The other nominees, meanwhile, have been asked to re-read their own films through the core issues of internationalism and immigration.

This political slant has brought an added charge to what was already a noteworthy group. Germany’s “Toni Erdmann,” written and directed by Maren Ade, swept the major prizes at the European Film Awards in December and won numerous international critics prizes. Denmark’s “Land of Mine,” written and directed by Martin Zandvliet, won multiple European Film Awards as well.

Australia’s “Tanna,” directed and co-written by Bentley Dean and Martin Butler, won two prizes when it premiered at the 2015 Venice Film Festival. Sweden’s “A Man Called Ove,” directed and adapted by Hannes Holm, also picked up a European Film Award and has earned more than $3.4 million at the U.S. box office. Farhadi, who won the Oscar in 2012 for “A Separation,” had picked up two prizes for “The Salesman” when it debuted at the 2016 Cannes Film Festival.

None of the films were made with America, much less its current administration, in mind, but all grapple with themes that have gained a vivid new relevance: Tolerance and understanding, cross-border relations and gender dynamics.

“Concerning this category, for me we’re all foreigners, so we’re all affected,” Ade said in a call from her home in Berlin. “I don’t care at all which countries [Trump has] banned or which religion or whatever, besides the fact is that I’m a woman and I feel he’s a very sexist guy. Still, we all made our films before, but it’s interesting the questions that come up now, like ‘What can cinema do?’ ‘Where do I stand?’ ‘How much do I care?’”

Ade’s “Toni Erdmann” is a dark, emotional comedy that deals with the estranged relationship between a father and his adult daughter. When he unexpectedly meets up with her as she is working at her corporate job in Bucharest, he throws her controlled existence into tumult. The film’s exploration of gender dynamics in the workplace, cross-generational differences and the morality of corporate thinking all take on a heightened feel in a post-Trump world.

With its WWII-era setting, Zandvliet’s “Land of Mine” outwardly seems the most traditional of this year’s nominees. It is based on the real story of German POWs, many only teenagers, forced to clear landmines from Danish beaches after the end of the war. In the wake of the travel ban, Zandvliet has noticed a shift in the way that interviewers have wanted to talk about the story, moving from the emotional to the political, a change he has found both satisfying and frustrating.

“When I first started doing the movie, I knew I wanted to comment on society, because in Europe at that point it was about the Syrian refugees,” Zandvliet said recently while in Los Angeles. Audiences, he added, are often surprised to find themselves sympathizing with young Nazi soldiers swept up by history. “And that’s also the point of the movie, that we shouldn’t hate or fear or judge in general. So people should be treated as individuals. We as humans are not so different after all, and you cannot just blame a gender or a country or a people.”

While Zandvliet understands that these issues have added resonance at this particular time, he feels sad that the travel ban has been the center of the focus, rather than the movies themselves establishing the conversation around them.

“I think as filmmakers what we want the most is to have our films out,” he said, “and I don’t think it’s just about the Oscars.”

We as humans are not so different after all, and you cannot just blame a gender or a country or a people.

— Martin Zandvliet, director and writer of “Land of Mine”

“Tanna” is the first fiction feature for Dean and Butler, both longtime documentarians. A tale of a forbidden love that goes against tribal traditions, the film was made in collaboration with native people on the island nation of Vanuatu, many of whom had never seen a movie before.

”I think it is challenging to globalization and the acceptance of diversity within the world and I think it is a very worrying time. For instance, the foreign-language category seems to me to be just perfect for that sense of embrace of diversity,” said Butler on a recent call from Australia. “The category itself is a celebration of diversity of views, of language and definitely not a celebration of white, Anglo-Saxon America.”

“And I think it says something about the universality of themes in the film, but those themes are present in the very category of foreign language,” added Dean. “This film, if there was a film that sort of sums up the magic and inclusive nature of cinema, this is it. People who had never seen a film before, they responded to it by just getting it straight away and then catapulting to the Academy Awards.”

“A Man Called Ove” is the story of an aging widower whose plan to commit suicide is interrupted by new neighbors, including a woman from Iran. Holm said he would hope that Trump might see the film.

“It’s a classical saga like Dickens, Mr. Scrooge, ‘Gran Torino’ and much more. This story has been told so many times about grumpy old men and then they become warmhearted and so on,” said Holm recently while in Los Angeles. “But as a storyteller it’s so important to tell this story again and again and again because someday we will have a Mr. Trump as president. So in a way it’s quite special to have these issues in this film with these things happening right now.”

The recent push toward internationalism within the academy’s ranks — last year 283 international invitees, including Ade, were among the record 683 extended membership — appears to be shoving against the confines of the foreign-language category as well. “A Man Called Ove” is also competing in the makeup and hairstyling category. Isabelle Huppert was nominated in the lead actress category for “Elle,” France’s foreign-language submission, while Gianfranco Rossi’s “Fire at Sea,” Italy’s foreign-language submission, was nominated for documentary feature.

Ade, Holm, Zandvliet, Dean and Butler individually considered emulating Farhadi and boycotting the awards ceremony, but all ultimately decided against it.

“In the first moments,” said Ade, “I had the same spontaneous impulse and reaction, ‘OK, now nobody can come. We’re all foreigners, it doesn’t matter which country we’re from.’ But then I thought, for me, I’d been traveling a lot to the U.S. in the last half-year and this government is new and it doesn’t represent at all the America that I know, that I met, that I like.”

Iranian-born “Ove” actress Bahar Pars, a Swedish citizen, is expected to be in Los Angeles for the Oscar ceremony. And three of the tribespeople from “Tanna” will be there too, hitting red carpets in traditional dress as they did when the film premiered in Venice. (Butler said that getting visas for the tribespeople, who travel under Vanuatu passports, itself required a long trip from the island nation to Australia.)

Holm emphasized that the problems raised by the travel ban for a group of Oscar nominees largely only mattered for the spotlight it brought to a larger issue.

“For me it’s not the problem that Bahar has trouble getting there, or Asghar Farhadi, the problem is so much worse for so many ordinary people in the world,” Holm said. “And you can’t forget that so many tragedies are now taking place all over the world. But having all these eyes on us, we can help and show our solidarity for the people who are really in trouble now, and not just the people who are going to a party.”

SIGN UP for the free Indie Focus movies newsletter »

Follow on Twitter: @IndieFocus

ALSO

The documentary category makes history, but not without Oscar controversy

Isabelle Huppert breaks through with the fearless audacity of ‘Elle’

DGA president blames producers for Hollywood’s lack of women directors

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.