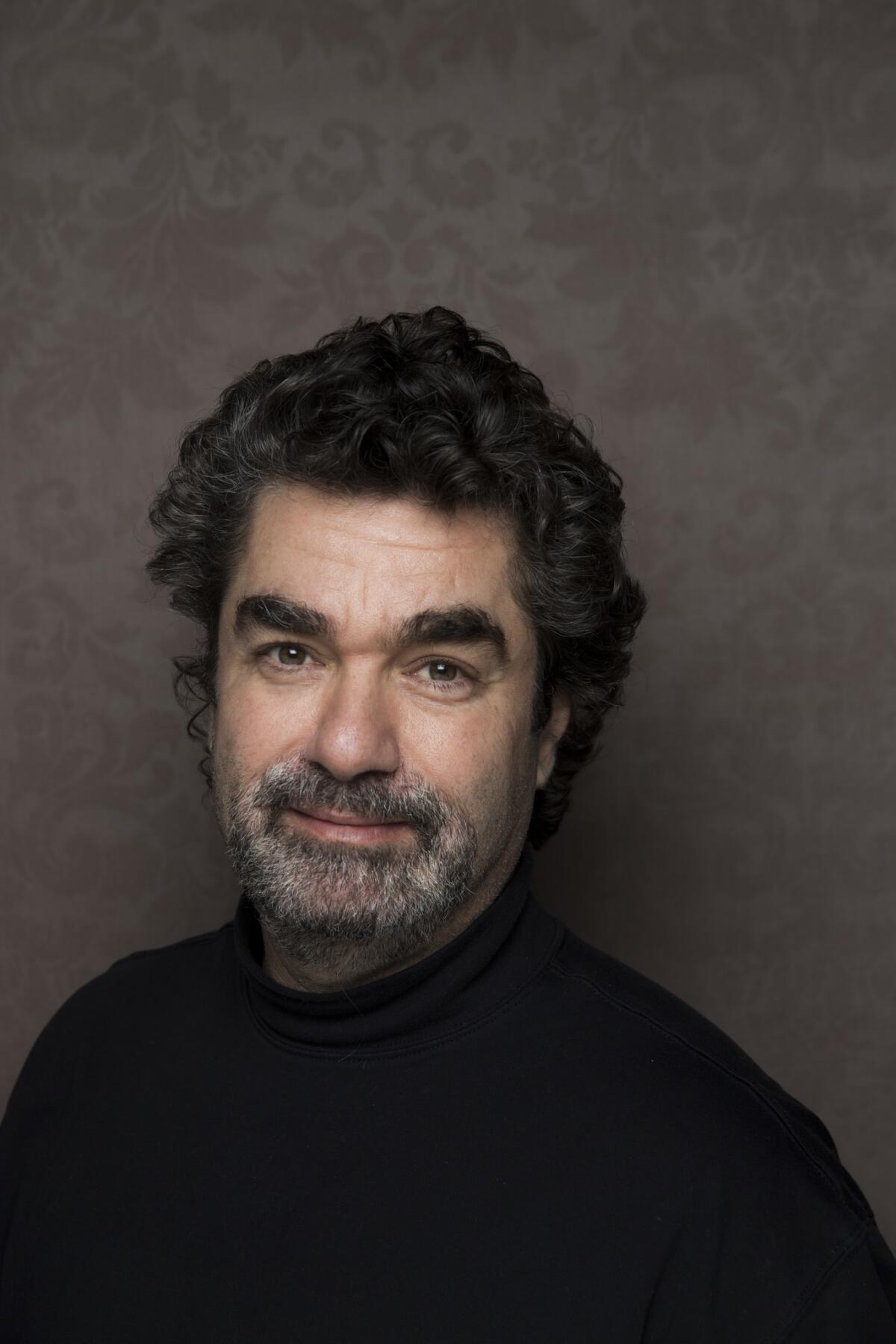

‘The Ted Bundy Tapes’ and ‘Shockingly Evil’: Why Joe Berlinger doubled down on the serial killer

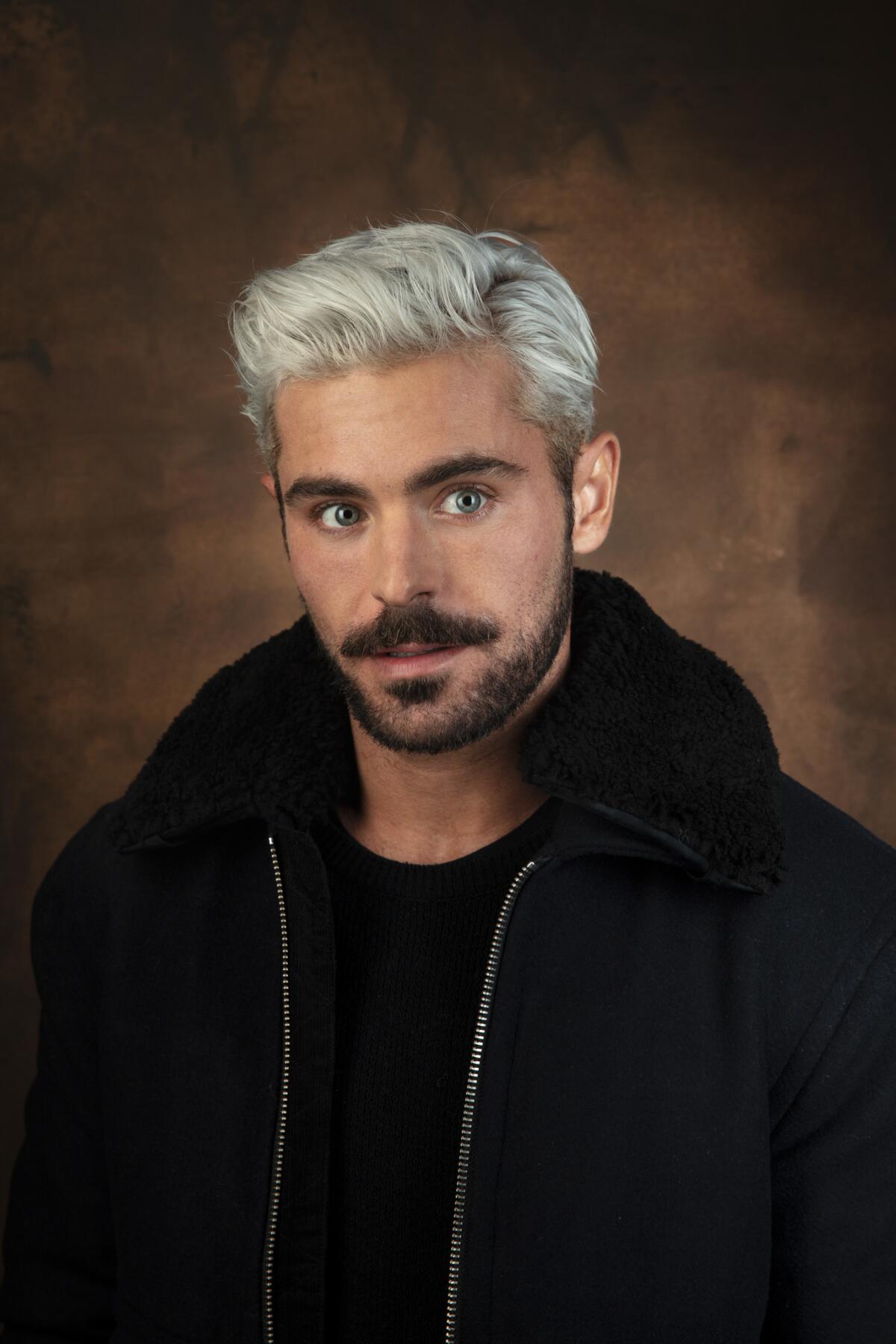

The timing was uncanny: Days apart, on the weekend marking the 30th anniversary of the execution of notorious serial killer Ted Bundy, Academy Award-nominated filmmaker Joe Berlinger (“Paradise Lost” trilogy, “Some Kind of Monster”) premiered his Zac Efron-starring Bundy film “Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile” at the Sundance Film Festival and unveiled the four-part docuseries “The Ted Bundy Tapes” to voracious true-crime fanatics on Netflix.

“It’s a little bizarre,” Berlinger admitted, stopping by the L.A. Times studio at Sundance. “I’d love to take credit for this master plan … but the fact that I even did both is somewhat coincidental.”

It was nearly two years ago that Berlinger was contacted by author Stephen Michaud with a tantalizing offer to dive into hours and hours of taped conversations with Bundy that Michaud and Hugh Aynesworth wrote into the nonfiction book “Conversations With a Killer.”

“He said, ‘I’ve never really done anything with these audiotapes that I did a book on,” said Berlinger. “’Do you want to listen to the tapes and see if you think there’s anything there?’”

The docuseries that would become “Conversations With a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes” was already underway with Netflix when Michael Werwie’s Black Listed script for “Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile,” a narrative retelling of Bundy’s crimes told from the perspective of his live-in girlfriend Elizabeth “Liz” Kloepfer, fell into his lap.

Within a month and a half, the feature film secured financing with Zac Efron attached to star as the duplicitous Bundy and Lily Collins as Kloepfer, whose 1981 memoir “The Phantom Prince: My Life With Ted Bundy” shed rare insight into the private life of the convicted killer.

Now, with both Bundy projects unveiled simultaneously — Netflix announced its acquisition of “Extremely Wicked” following the film’s Sundance premiere and the trending success of its “Ted Bundy Tapes” launch — Berlinger has found himself in the controversial business of Bundy. And audiences are wrestling with their own fascination with the man who confessed to murdering and raping as many as 30 women and girls across seven states in the 1970s.

The question of the hour: Why is Joe Berlinger so obsessed with Ted Bundy — and why can’t audiences look away?

The timing of these two Ted Bundy projects makes for quite the coincidence. What sparked your interest in exploring all things Bundy?

It’s a story that’s been told many times, so my bar was high. But I listened to the tapes and I thought there was an amazing opportunity to go inside the mind of a killer and tell a story, with a little distance and with some freshness, because we had this perspective from Bundy himself.

How did “Extremely Wicked” fall into place?

There was no intention to do a scripted film, but I was sitting with my movie agent at CAA and I mentioned I was doing this Bundy series. He sent me the script and on the plane ride home I read it, and I texted him from 30,000 feet saying, ‘Oh my God, I love this script.’ I loved it because it provided a new way into the story, a fresh way, and it allowed me the opportunity to turn the serial-killer genre on its head. [Weeks later] at a CAA meeting Zac [Efron]’s agent says, ‘That’s interesting – Zac is looking to do something different. What do you think about Zac?’

What did you think about Zac Efron? How familiar were you with his work?

I actually think Zac is a terrific actor who hasn’t been given enough opportunities to show his range. And I thought if Zac was willing to play with his teen heartthrob image, that’s a piece of reality to bring into the movie that I thought would be very effective. I felt like it would be a bold choice for both of us, and if it worked, it would really work.

You’ve both zeroed in this element of charisma being vital to Bundy’s ability to pull off so many crimes. That’s a quality Efron has demonstrated throughout his career, so on paper, that tracks.

But when an agent says to you, ‘Do you want Zac to read the script?’ it’s not a light decision, because for somebody at Zac’s level to read the script it’s a reading offer. That means if he says yes, you’re obligated to use him. But my reaction was immediate. I was at JFK on South African Airlines with the doors closing. Instead of going, ‘I need to think about that and I’m going to be incommunicado for the next 36 hours because I’m on my way to the Skeleton Coast of Namibia...’ I’m having to make a quick decision: ignore the email, say yes, or think about it? I was like, ‘Sounds like a great idea. Boom.’

What gave you insight that he had Ted Bundy in him? Had you seen the “High School Musical” movies?

You know, my daughter was a total “High School Musical” fanatic. I can’t say I studied his oeuvre before making the decision — I just was always aware of him as an actor. He’s done a couple of excellent serious roles in films that haven’t necessarily worked as well as they should have, and I just thought it was interesting – I liked the idea of playing with that image.

How did working simultaneously on these two projects help each inform the other?

On the most basic level I was deeply immersed in the subject and a total expert going into the feature film. The department heads, like the art director, production designer, costume designer, everybody had this amazing resource back in New York to tap into, which was my documentary team. Photo references were sent over. Any time we had a factual question because we changed the script during prep and added some stuff, there was this doc series in the making that we could tap into.

Why was Liz’s point of view an important perspective to take in the scripted film, in counterpoint to the Bundy tapes?

I want the audience to feel that same revulsion and betrayal that Liz felt, because that’s what I’m making a movie about. We want to think that a serial killer is some social outcast, two-dimensional monster because that implies that they’re easy to recognize and therefore you can avoid them. But the reality, in my opinion, of evil and those who do evil in this world are often the people closest to us and whom you least expect.

That’s a lesson that can’t be learned enough, whether it’s a priest who commits pedophilia and then holds Mass the next day, or the CEO of a polluting corporation who goes to bed at night knowing he’s killing tens of thousands of people and is suppressing climate change research in the interest of shareholders ... that’s a form, in my opinion, of sociopathic compartmentalization.

And as a father of daughters in the prototypical Bundy victim age, that’s a lesson I want my children to have, and a lesson I want to impart with people about the nature of evil – that it’s often done by the people you least expect and most want to trust. And therefore, people really need to deserve your trust.

You made your narrative directing debut with the 2000 horror film ‘Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2.’ What do you think has attracted you to exploring these dark terrains in different storytelling forms?

I think all of my work is about what motivates people to do good and bad. I think my intent with “Book of Shadows” was overly ambitious, versus what people actually wanted. [Pauses] It was not a well-received film, as I’m sure you’re aware.

I think all of my work is about what motivates people to do good and bad.

— Joe Berlinger

There are many horror fans today who will stand up for it.

Which I appreciate. The problem was that the communication of the film got a little muddied, because at the 12th hour the studio didn’t understand what I was doing and recut the film against my will. I was making fun of the idea of doing a sequel, and I was looking to give some social commentary which has become really prescient – everybody celebrated the [original “Blair Witch Project”] marketing hoax, Time, Newsweek, every news outlet was like, “Isn’t this amazing? The studio lied to everybody and said it was a real documentary and it became a phenomenon!”

The fact that nobody in the news media took a step back to analyze, well, it’s not good that a marketing campaign was a complete lie to get people to see a movie.… And boy, have we come to be in those times where in the world of fake news and alternative facts, where news is now entertainment. When I made that film I couldn’t have imagined that things would get as bad as they are now.

How would you describe your relationship to the “true-crime” genre?

Wikipedia calls me a true-crime pioneer. I like the “pioneer” part. The true-crime part makes me cringe a little bit because I’d like to think my explorations of true crime in my documentary work have a layer of social justice. But there’s plenty of true crime out there that just wallows in the misery of others.

And much of our fascination with true crime is a seeking of understanding of the horrific things people do to each other —

Right, and that’s why I scratch my head where people can look at [“Extremely Wicked”] and say that we’re glorifying [Bundy]. It’s a very serious film. Because Bundy defied all stereotypes of what a serial killer was. And that’s why a film that portrays not killing but the seduction of the serial killer which allowed him to elude capture for so long — while also making a commentary about the nature of our obsession with true crime — to me is the opposite of glorification. It’s a very highly aware, self-critical exploration of these phenomena.

While working on both Bundy projects, were you in dialogue with the families of his victims – and did that factor into how you handled the material?

Not really, to be honest with you. But it did. I feel a great sense of responsibility when I’m telling a victim’s story. In fact, the lesson I learned was on “Paradise Lost.” When we went to make the original “Paradise Lost” we showed up a week after the arrest and the entire world thought that these guys were guilty … when we went down to Arkansas a week after the arrest and embedded in the community for seven months before the trial started, we thought we were making a film about kids killing kids.

We spent time with the families of the victims, we convinced them to give us access to their story, because we felt at the time this was an important thing for other parents to learn about. That was our pitch to them and it was very sincere and authentic. But over time we became convinced that the kids were innocent. And by the time we left the trial, we were utterly convinced that the West Memphis Three had just been convicted for crimes they weren’t guilty of.

So when the movies came out the families were horrified, and hated us, which I understand. Because there’s no closure when you’ve lost a child to violence, or lost a child, period, but the healing process is predicated on the serving of justice. Eventually two of the three families came over to our point of view and thanked us for our work and said, basically, that they would never want the wrong people to be wrongfully convicted.

One family to this day believes the West Memphis Three are guilty and that we did a terrible disservice.… All of that is extremely painful. The last thing I want to do is to make victims feel worse, and I think the rest of my track record demonstrates my commitment to victims. And I have nothing but sympathy toward the family who hates me because I could never imagine being in their shoes. But the lesson I learned from that is you need to be extremely sensitive to the victim’s families.

In this instance, when we started reaching out to [Bundy’s victims’ families] they felt like the story has been so oft-told, that the intrusion of more people reaching out to them was actually what was painful. So I decided to stop reaching out seeking cooperation from family members and instead decided to make sure that nothing about the Bundy tapes had new information about what happened to their children.

What sort of information did you purposefully leave out of the docuseries?

A handful of new information that we decided not to use because it would be new to the public and that wouldn’t be fair. But with regard to survivors, we reached out to Carol DaRonch, the Utah woman who survived and escaped and was able to ID him and start the legal proceedings, who was very reluctant but eventually agreed to participate. And of course for the movie, it was very important to see Elizabeth Kloepfer.

As a documentarian who has wrestled with these ethical issues, what’s your take on the controversy surrounding the Michael Jackson documentary here at Sundance?

I’m not commenting specifically about this filmmaker or film because I haven’t seen it, but I always strive to have all sides included in a film. I think at the end of the day in all films, whether it’s a documentary or not, you make a thousand subjective decisions. Often, you’re not going for the literal truth of a situation, you’re going for the emotional truth.… You trust a filmmaker to condense and give you the emotional truth of a situation. And I think sometimes people are afraid of showing all sides, but showing all sides doesn’t mean you don’t have a point of view or an opinion. So I would hope that this film represents the emotional truth of what went down.

With so much Ted Bundy research and all this darkness swirling in your head, do you have nightmares or do you sleep well at night?

I actually don’t have that many nightmares, I’ve been doing this for so long. I have trouble sleeping in general — I sleep in two-hour bursts. I wish it was otherwise! But when I walk into my house I try to leave the work behind … which is not always successful.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.