What do Andre the Giant, Frank Sinatra and Dead Kennedys have in common? The Olympic Auditorium

Nestled against the 10 Freeway near the convergence of the 110, 101 and the 5 is a beige concrete slab of a building that would be easy to miss if not for the wall-sized mural of Jesus painted on its exterior.

Born as the Olympic Auditorium 91 years ago, it sits quite literally at a crossroads of L.A. subcultures.

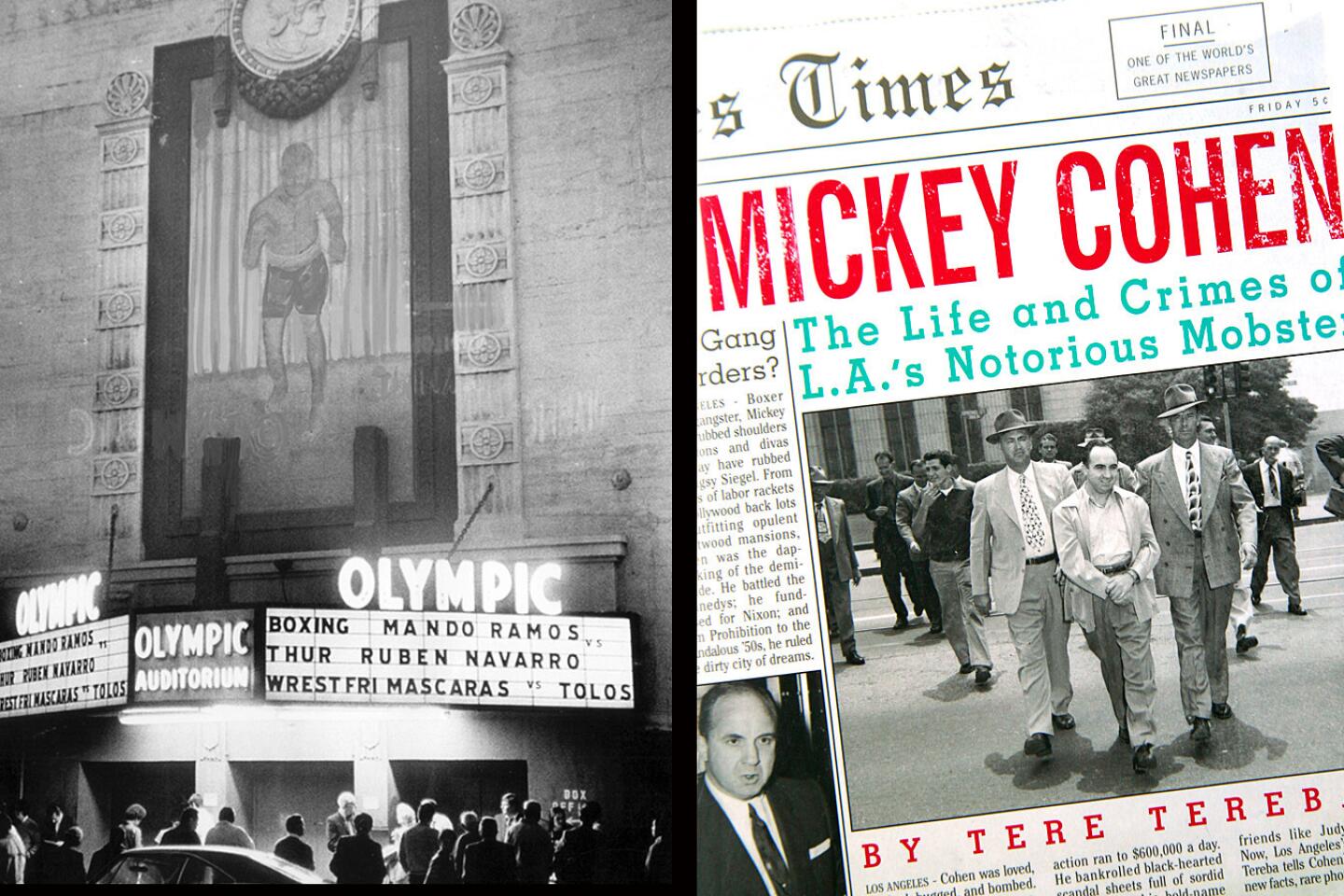

It was L.A.’s biggest and most populist entertainment complex for much of the 20th century. A boxing arena, a roller derby rink, a wrestling mecca, a punk rock playground and, most recently, an evangelical church on the dilapidated corner of 18th Street and Grand Avenue.

Now it’s a reminder that not every aspect of L.A.’s entertainment history is pretty, polished or the product of Hollywood magic.

“The Olympic is connected to Hollywood in some ways, but what’s most interesting is its connection to these other parts of the L.A. story that don’t often get told,” says Steve DeBro, an L.A. native who’s spent the last few years researching the history of the Olympic Auditorium for a documentary he’s making about the venue.

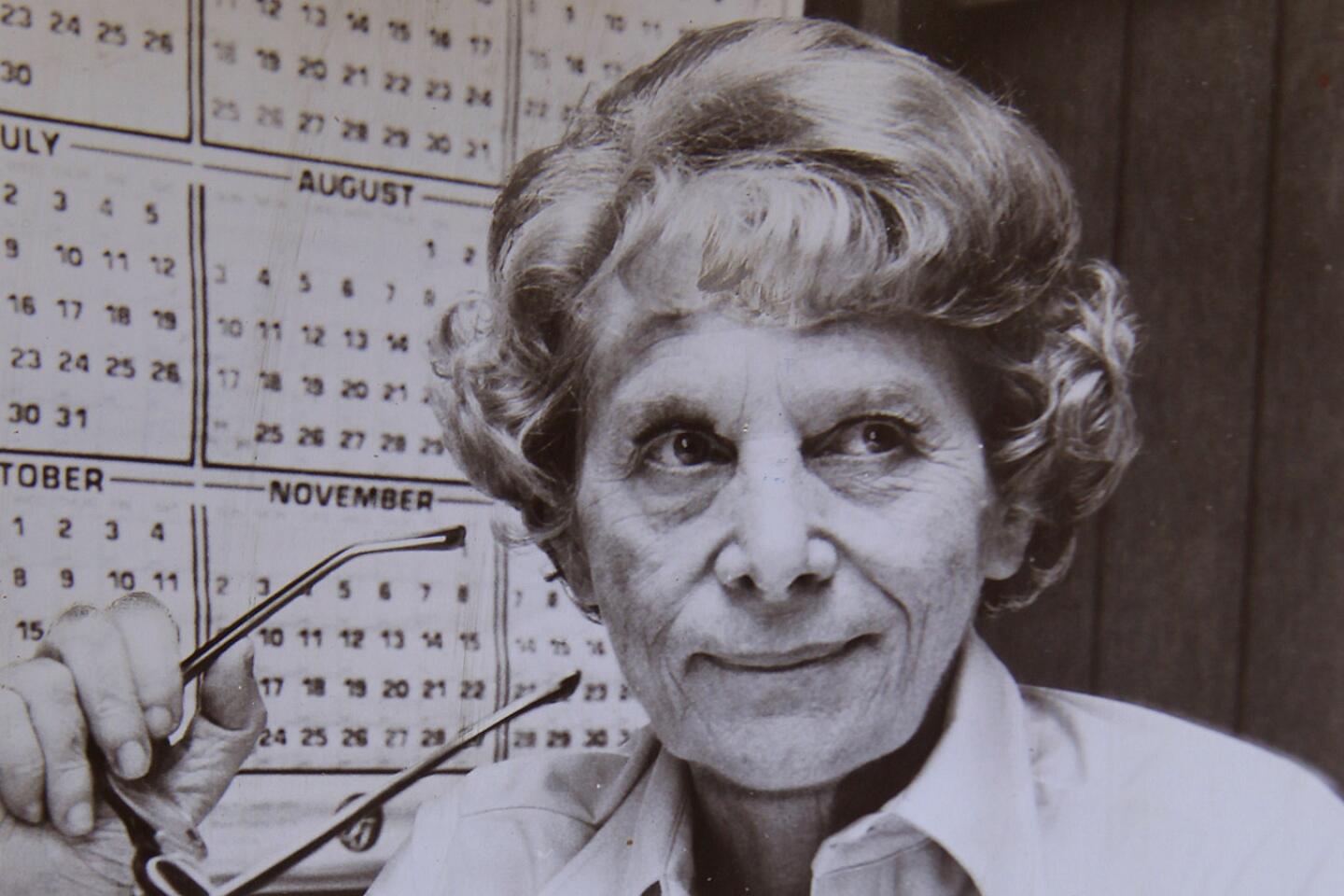

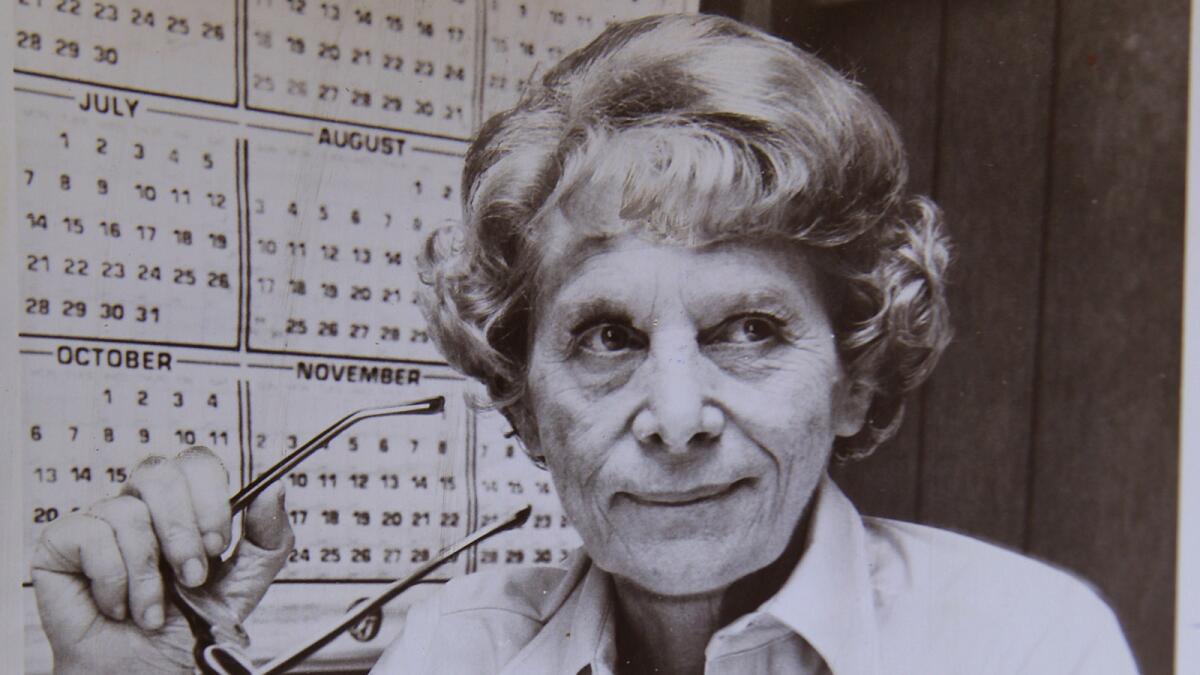

“It’s the story of L.A.’s working-class people, it’s the story of Mexican Americans, of Aileen Eaton [the Olympics’ most successful promoter], who succeeded in a very macho man’s world,” DeBro says. “Despite that movie stars went there, it’s just as important to me that guys who were laborers went there to blow off steam on a Thursday night to watch boxing. Or went to see wrestling on a Wednesday. All these stories connect to our past, a past which L.A. is really good at forgetting.”

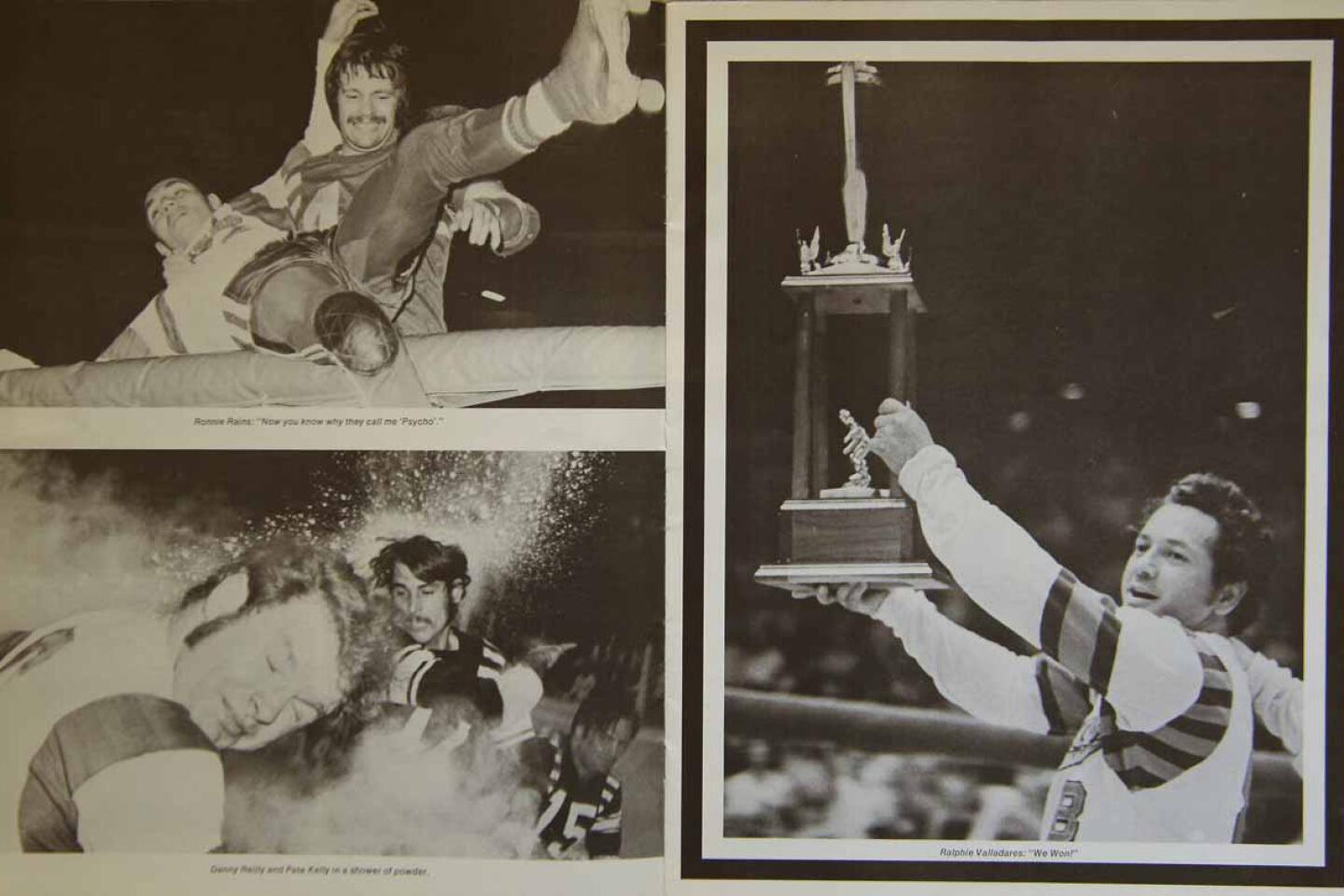

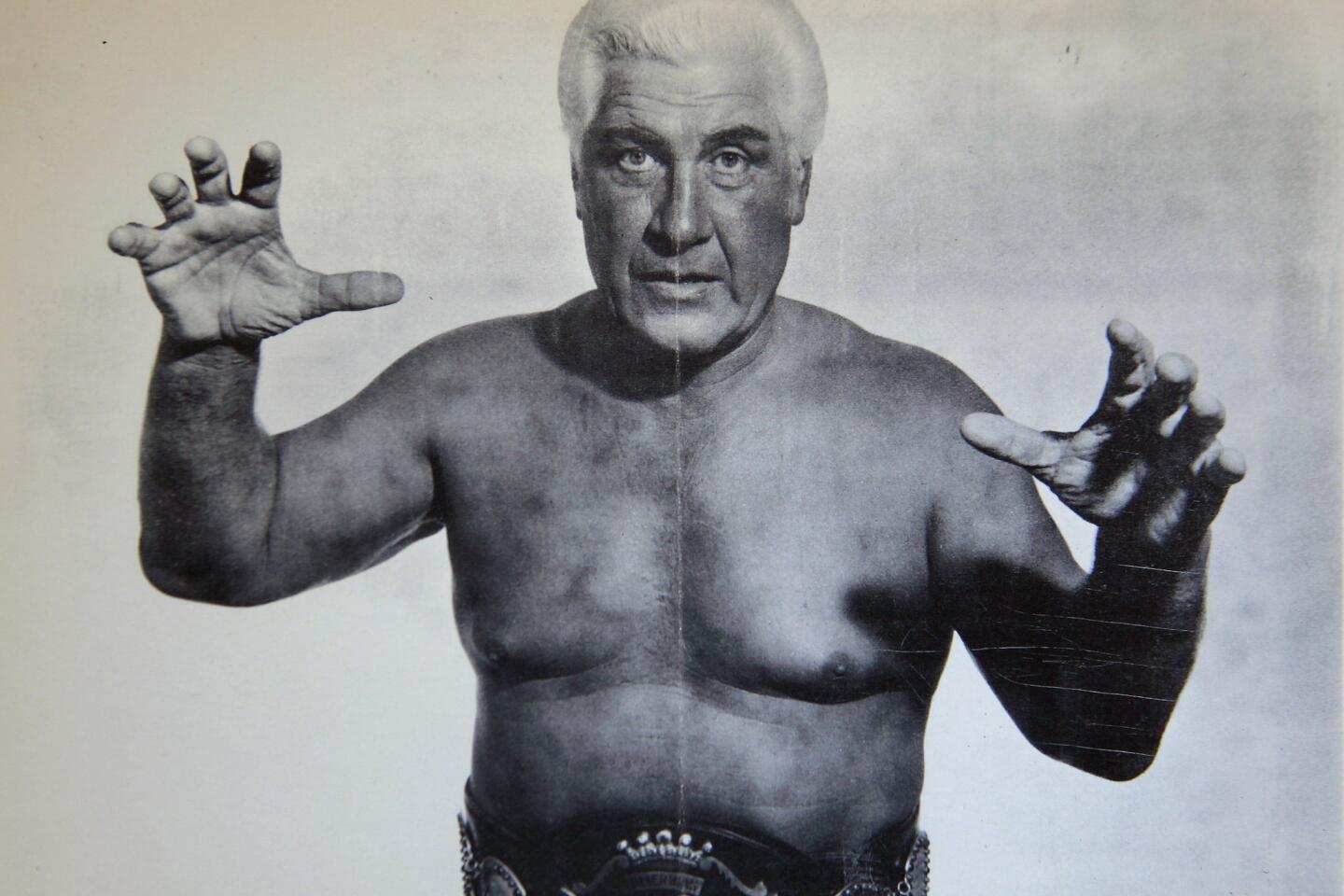

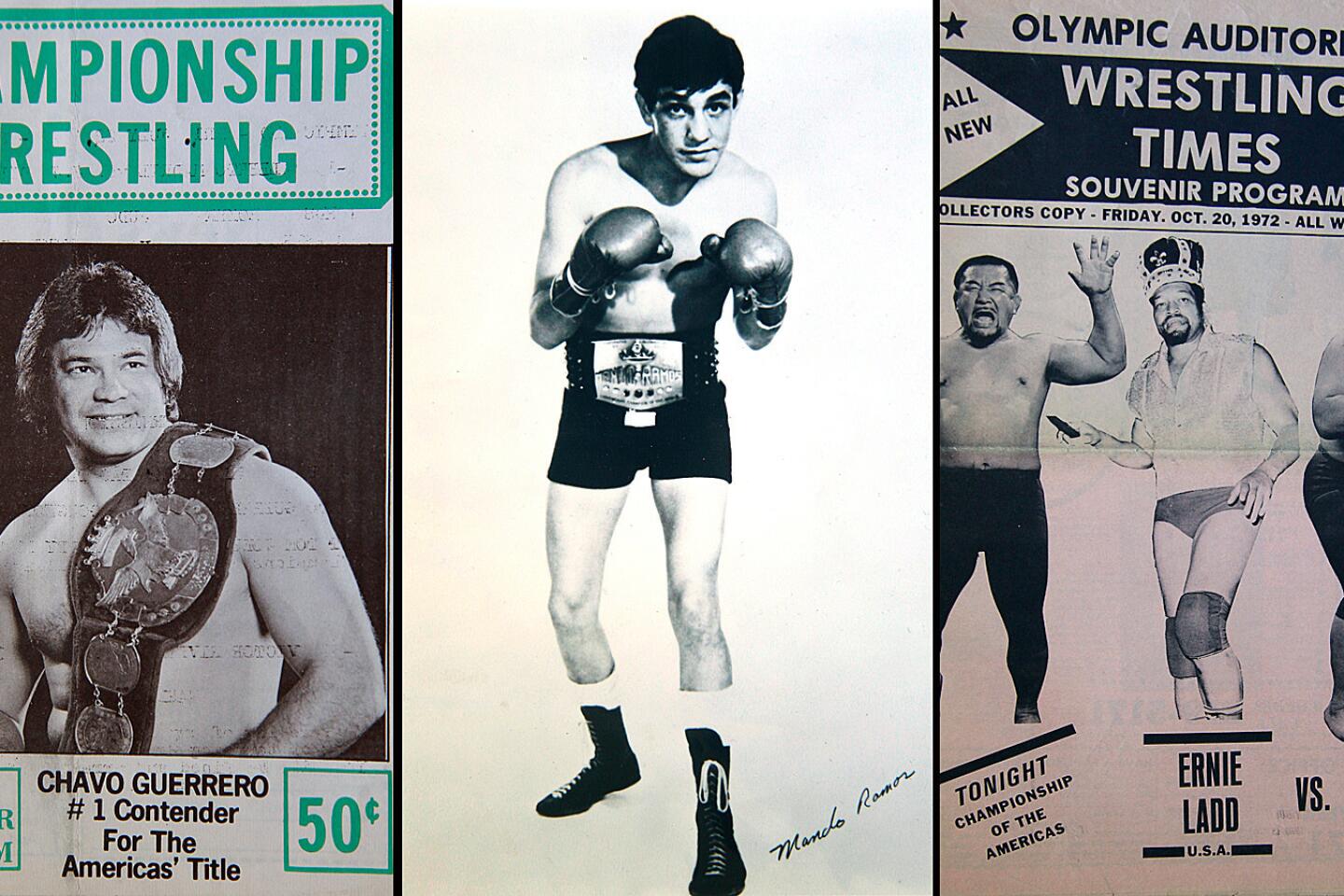

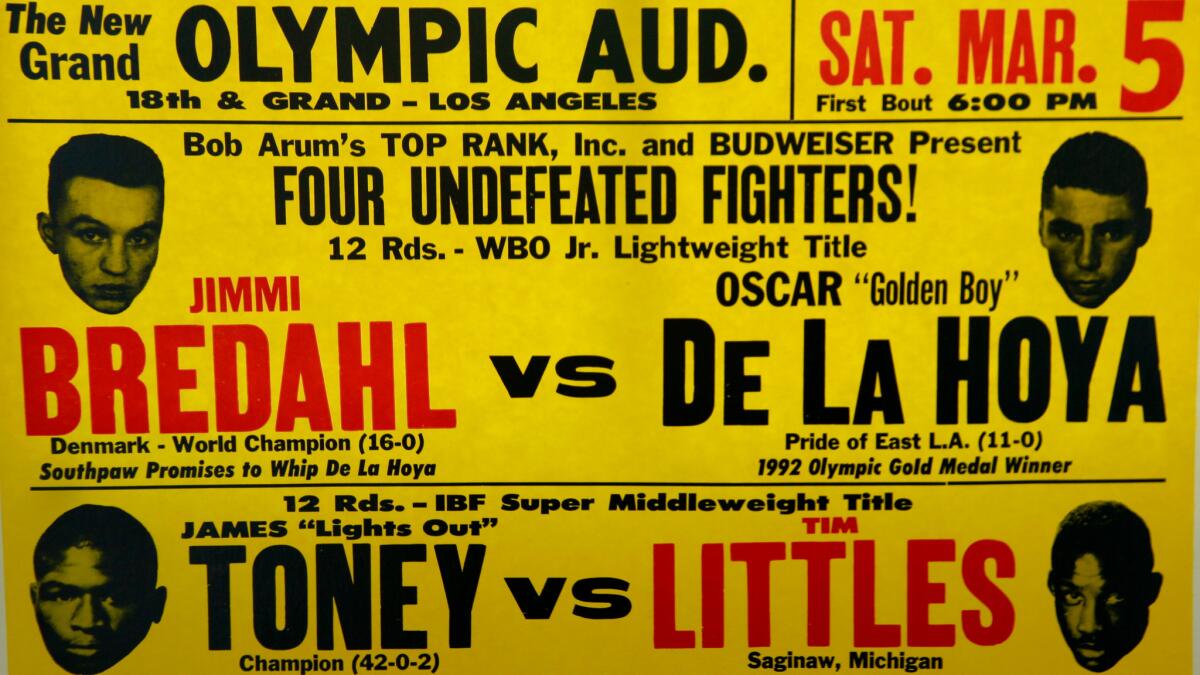

DeBro, 50, is one of many Angelenos raised on the orchestrated mayhem of the Los Angeles Thunderbirds’ roller derby games or wrestling matches that featured giant masked men with names like the Destroyer and Mil Mascaras battling it out in tiny unitards. But the 7,000- to 10,000-seat venue (depending on the era of the event) was best known for boxing matches featuring the likes of Danny “Little Red” Lopez, Carlos Palomino, Mando Ramos and Joe Frazier.

The high brow would often roll their eyes at the mere mention of the place, but at the Olympic an eclectic mixture of writers (Joan Didion, Charles Bukowski), celebrities (Mae West, Clint Eastwood) and mobsters (Bugsy Siegel, Mickey Cohen) mixed with the salt of the city, brought together by blood sport and high-energy theatrics (Little Richard rocked the place so hard during his 1970 concert that the stage collapsed).

“The Olympic was totally insane,” says Gary Tovar, a pioneering L.A. promoter who put on hard-core punk rock shows at the Olympic in the early 1980s when few places would book such aggressive concerts.

It had roller derby, it had fights....I knew the Olympic would tolerate what we did when no one else would.

— Punk rock promoter Gary Tovar

“It had roller derby, it had fights where people would pee in cups and throw it at the boxers. I figure punk rock insanity they wouldn’t mind because they were already insane,” he says. “I knew the Olympic would tolerate what we did when no one else would.”

Today parishioners of the Glory Church of Jesus Christ, a Korean evangelical ministry, sing hymnals under the old metal boxing truss that once illuminated the ring for fighters like Art Aragon and Sonny Liston. Rows of numbered, red folding chairs that once held throngs of screaming Andre the Giant fans now face a pulpit and choir. And cups passed among the audience today contain donations rather than beer. Otherwise, the arena — its narrow hallways, low ceilings and shuttered hot dog concession stand — looks much the same way it did when Enrique Bolanos fought there well over a half century ago.

“There are echoes of the original arena there,” says DeBro, who reached out to the church and has been able to shoot parts of the film, “18th & Grand,” inside the building. “That spot where the ring was, where blood was spilled and people died, is the same spot where devout parishioners are now talking to God. To me it’s a holy shrine, and it always was — it was a shrine to the people who went there to see boxers beat the ... out of each other, or theatricalized violence with wrestling, or hear music. It was always a place of worship.”

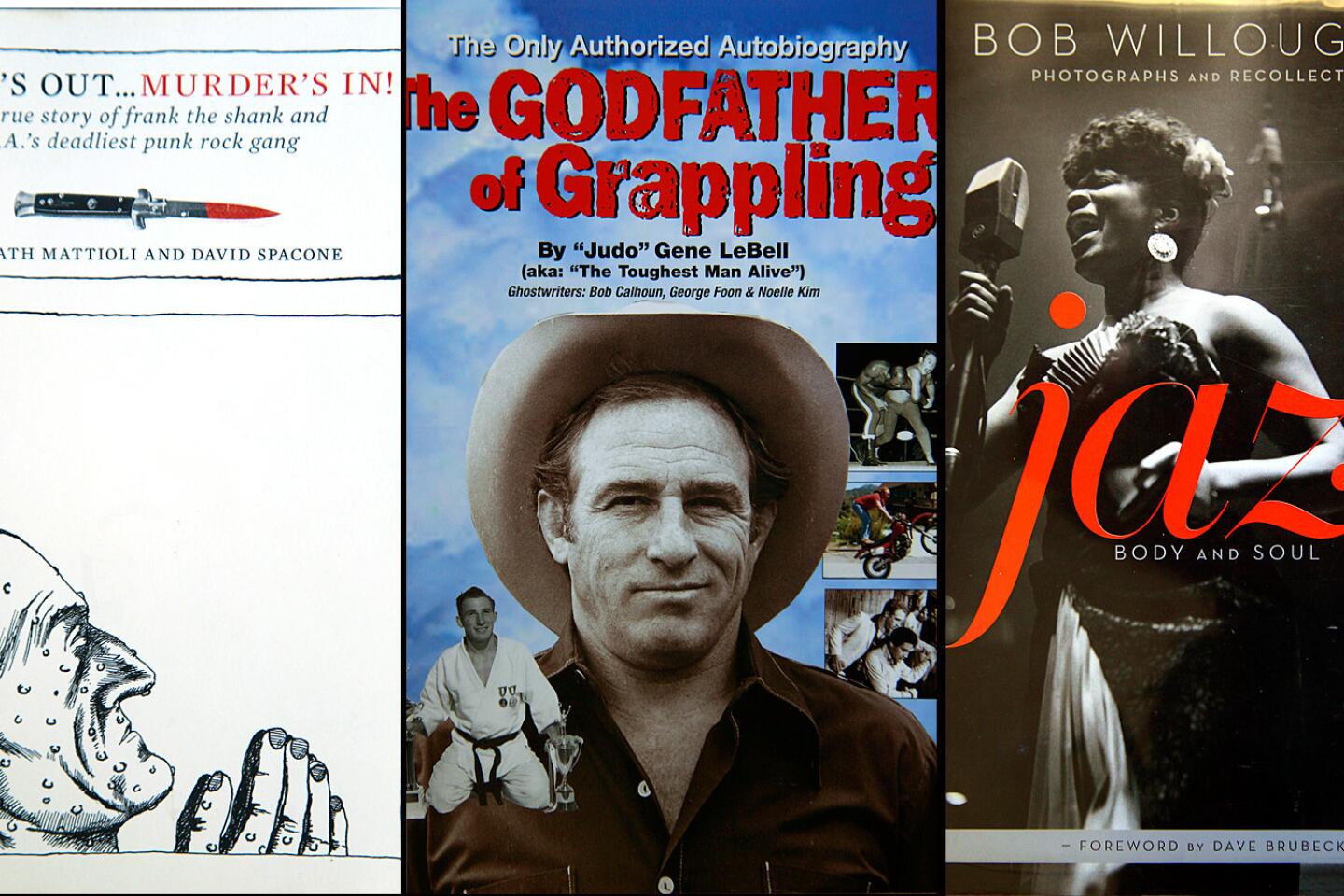

“18th & Grand” is still in production, evidenced by the piles of memorabilia and research throughout DeBro’s West Hollywood home office: reference books on L.A. and boxing, wrestling posters, punk rock fliers, photographs and news clippings. He and executive producer Willard Ford successfully raised over $61,000 on the crowdfunding site Kickstarter, and they hope to have their film completed by year’s end. The documentary is an outgrowth of DeBro and Ford’s Olympic Auditorium Project, an online hub where fans can connect and share memories, organize events dedicated to the Olympic’s memory and discuss the very real possibility of putting on one more boxing event at the venue (promoters have apparently approached the church).

“We realized the passion and love so many people had for the Olympic Auditorium,” DeBro says. “Boxing fans, roller derby people, wrestling, punk rockers. All these subcultures have this love for the place. It felt like it was more than just a doc, it’s like dialogue between past and present. There’s a lot of power in that strange, sarcophagus-like building.”

Once a marketer in the music business before he became a casualty of the shrinking industry, DeBro became interested in the history of the arena when a friend showed him photos by Olympic house photographer Theo Ehret from the mid 1960s to early ’80s. The discovery dovetailed with his interest in starting his own multifaceted production company, GenPop.

“The photos reminded me of my childhood growing up in L.A.,” said DeBro. “It reminded me of black-and-white TV, watching roller derby, wrestling and boxing with my dad. Richmond 9-5171: It seemed like we all knew that phone number. The photos sparked my interest. I was starting to see the scope of this narrative and how it fits into the history of L.A., the violent birth of the city, and how it connected to so many different parts of the city.”

A new monster convention hall

The Olympic was built in 1924 when the city’s population was exploding (going from 575,000 in 1920 to 1.2 million by the decade’s end), challenging a small police force with increasing amounts of gambling, vice and organized crime. Its construction was bankrolled by a who’s who of Los Angeles millionaires — oil men connected to tycoon Edward Doheny, real estate moguls, boxing promoters. It was named in anticipation of the 1932 Olympic Games in Los Angeles.

A Times article that ran on Aug. 4, 1925 — the day before the venue’s opening — described the Olympic as “a new monster convention hall and recreation stadium” that would seat more than 15,300 (though how is anyone’s guess). It came in way over budget at $500,000, but it featured a “handsome lobby” and electric fans that circulated the air “every eight minutes.” Legendary boxer Jack Dempsey was on hand for its opening, and the venue became a fashionable spot for stars like Valentino to see a fight — or an opera.

A depression-era slump meant thinning attendance until Aileen LeBell and her future husband, Cal Eaton, were brought on in 1942 by then-owners the L.A. Athletic Club to manage the failing property. They immediately dropped ticket prices and began promoting events to the general populace rather than the moneyed crowd of the venue’s past: “Call Richmond 9-5171 for your tickets!”

By 1965 Aileen Eaton had begun promoting weekly televised boxing matches on KTLA featuring the city’s seemingly endless supply of boxing talent. She parlayed the show’s viewership and created one of the most successful weekly boxing promotions in the country. She went on to use the same template for wrestling, offering televised spectacles from the Olympic each week that included roller derby.

“She really helped popularize the games,” says former roller derby star John Hall, who skated with the Detroit Devils before becoming a general manager for the L.A. Thunderbirds . “The shows were syndicated, and for years those KTLA broadcasts were the network’s top-rated show. It was that, and wrestling and boxing, all of which happened on the same floor in the same week. We’d skate Tuesday, then they’d drag the track outside and cover it up so they could bring the ring in and assemble it for wrestling on Wednesday and Friday, or boxing on Thursday. We’d drag the [roller] track back out on Saturday and Sunday and we start all over again.”

East L.A. heroes

The Olympic also became a destination for Latinos who flocked to the arena for luchador matches on Wednesdays and fight cards on Thursdays. The matches often featured Mexican nationals and locals, boxers who appealed to the otherwise underserved neighborhoods of East L.A.

“It was a place where Mexican Americans and Mexican nationals living in Los Angeles could go to a root for their heroes,” says Gene Aguilera, 62, who grew up in East L.A. and is the author of “Mexican American Boxing in Los Angeles.”

“You could take the bus there or even ride your bike there because of the proximity to East L.A. And it was entertaining. You’d see the gamblers in their little section, then another section you’d see Eaton and her matchmaker Don Chargin. Then in another section you’d see the celebrities of the day: Ryan O’Neal, Richard Pryor. It was where celebrities and Chicanos and gamblers and everyone would all mix together.”

Pulling from another side of L.A., the venue also served as a Hollywood film set. Movie shoots included Buster Keaton films, the original “Manchurian Candidate,” “Rocky” and “Raging Bull.”

By 1980 Aileen Eaton retired, box office sales dropped and the area surrounding the Olympic deteriorated along with the rest of downtown L.A. Now owned by the Needleman family (the Orpheum), the Olympic became one of the first Los Angeles venues to feature hard-core punk shows outside the confines of a small club.

“I had to talk the Dead Kennedy’s into playing there,” says Tovar, who booked 25 shows there featuring multiple artists from 1982 to 1986. “They thought it was arena rock. I was like, look, it’s in a bad area, it’s old, beat up. It’s not a glamorous place.”

The venue was renovated and reopened as the Grand Olympic in 1994 when Oscar De La Hoya won his championship title there. But it closed down in the early 2000s because of poor attendance.

The Olympic’s mural of boxer Dempsey was painted over and its marquee ripped down by the time the church bought the six-acre property for a reported $25 million in 2005.

Now each Sunday udon noodles are served on fold-out tables in the parking lot off Hope Street, families dining where the roller track was once stored on off nights. Inside, childcare is offered in several small rooms off the old backstage area. Near thick masses of lighting cable, an old metal rack once used for employee timecards now holds pledge notes from parishioners who wish to fund the church’s religious missions.

There’s a lot of ire in the boxing world over the Olympic becoming a church. A Facebook group called “Don’t You Hate It When Your Favorite Venue Becomes a Church?” has passionate laments about the Olympic.

DeBro thinks the criticism is misplaced. “I get lots of comments that are derogatory toward the Koreans or the church,” he says. “My feeling is different: Without the Koreans buying the building, most likely it would have been torn down and become condos or a big box store.”

Follow me on Twitter: @LorraineAli

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.