Review: ‘Dropped Names’ by Frank Langella dishes on fellow actors

Dropped Names

Famous Men and Women As I Knew Them

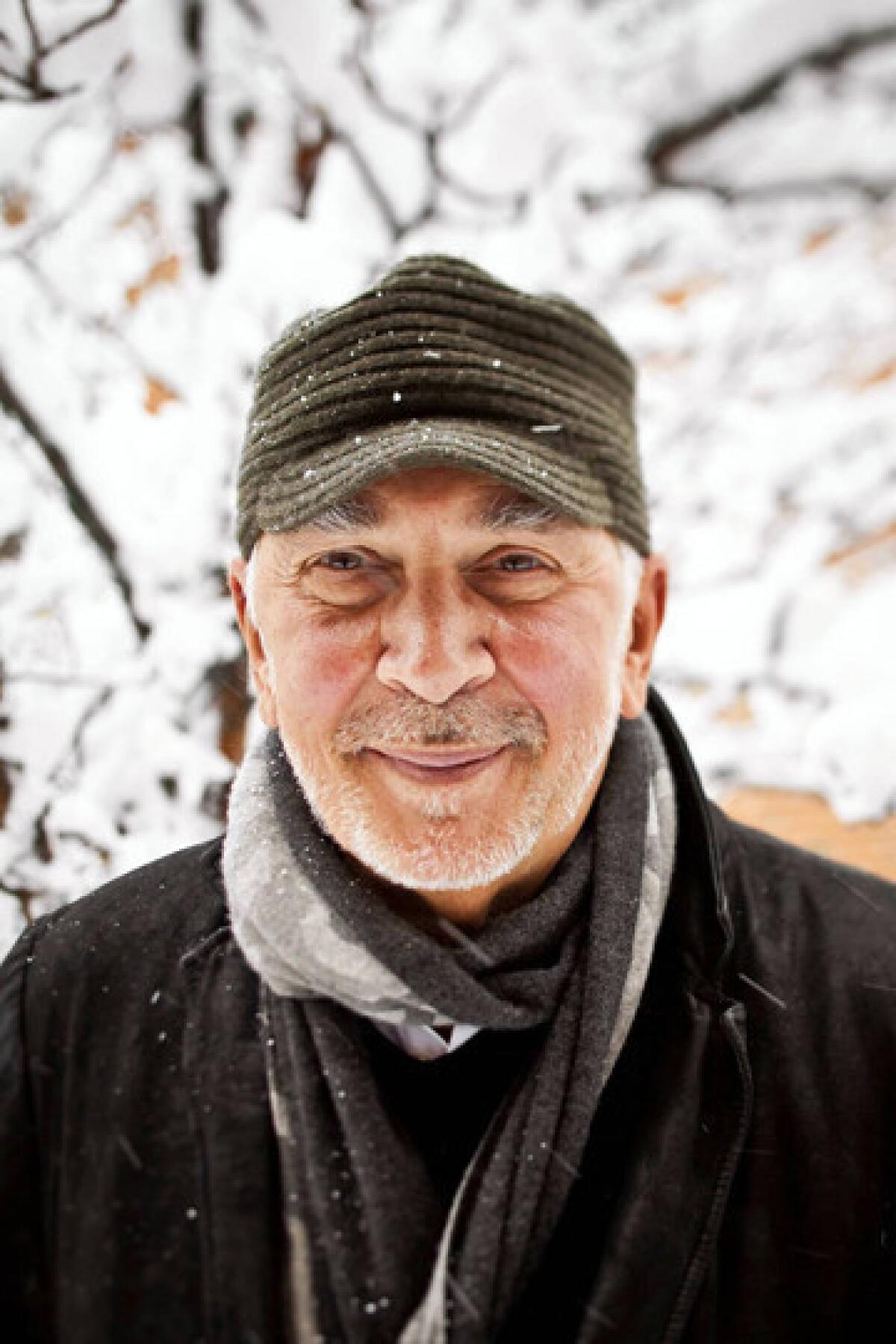

Frank Langella

Harper: 356 pp., $25.99

Frank Langella’s “Dropped Names” is a different kind of memoir. Rather than recapping his life story, the veteran stage and screen actor offers a series of quick sketch profiles of those he’s crossed paths with whose fame, generally speaking, outshines his own. Intimately acquainted with the capriciousness of the limelight and its warping effect on celebrity souls, the book has wicked fun placing its subjects (all dead save socialite Rachel “Bunny” Mellon) on Dr. Langella’s couch, where the patients, in a highly unusual twist, rarely get a word in edgewise.

Unlicensed to practice psychoanalysis (though no stranger to therapy), Langella sometimes seems to have an ax to grind — that of an accomplished actor deprived of the stardom granted to his inferiors. (A three-time Tony Award winner, Langella is best known for his stage and screen portrayals of Dracula and Nixon — roles for which, this ruthless book suggests, he was ideally cast.) But the wit and eloquence of his writing more than make up for the superior tone and not always convincing snap judgments. In the end, “Dropped Names” lives up to its billing as a memoir, leaving the reader with a rawer sense of Langella’s personality than likely would have been possible through a more conventional autobiography.

A warning is issued in the preface: “Don’t turn the page if you like your stories spoon-fed or sugar-spred. I didn’t always like some of my subjects, and I’m quite certain some of them found me less than sympathetic.” He further cautions that there will be “a fair amount of forks to the eye and knives to the throat; even a self-inflicted wound or two.”

The violence of the imagery is in keeping with his description of his Bayonne, N.J., upbringing, in which he was “raised by a pack of Italian wolves who hadn’t known a demitasse from a debutante.” Langella is an uncommonly elegant man, an actor of piercing intelligence and seemingly implacable self-assurance. But lurking beneath this dapper surface is a street fighter. When an actor with an ego comparable to his enters his vicinity, he leans in for a shoulder bump.

It doesn’t take a lab technician to detect the high level of testosterone in his summation of a few Hollywood notables:

Yul Brynner: “The word I passed Yul’s lips more often than perhaps any actor I have ever known, and it is a pronoun that comes quite easily to most of us.”

Anthony Quinn: “‘Kneel!’ Anthony Quinn seemed to be saying when first we met.”

Charlton Heston: “It was as if he had appointed himself the forever Numero Uno on the call sheet of life.”

Paul Newman: “Paul loved the craft of acting but the burden he carried was not, in my opinion, his good looks. He had no danger. And it is essential for a great actor.”

Laurence Olivier: “A master of deception who, long ago, I sensed, had lost touch with the simple act of just being.”

Richard Burton: “Could anyone, I wondered, be so unaware of what a crashing bore he had become?”

Even a nonthreatening presence such as Roddy McDowall (“I watched him work the room like a cordless vacuum cleaner, sucking up celebrity droppings”) comes in for a sucker punch. If Langella’s eye for detail weren’t so mercilessly good, this sort of thing would get irritating quickly. But he’s able to conjure an entire milieu with a few choice nouns, as he does in his description of Elizabeth Taylor’s overstocked movie queen bathroom, with its bowls of Q-tips and cotton balls spilling over like a New England snowdrift.

What was he doing counting the emery boards and bottles of witch hazel in Taylor’s private oasis? For a brief moment, the two courted in a bizarre romantic comedy that he ungallantly recounts as a series of boxing rounds. (Langella’s competitive streak is gender neutral: He’ll lock horns with any order of big game, even if they don’t have horns to lock.) But titanic personalities inspire his most vivid writing, and the scene of Taylor at home in a caftan luring Langella up the stairs to her boudoir is worthy of Billy Wilder.

“‘Oh, baby, I’m not going to make it,’ she said, howling in mock agony, like a woman trying to climb an icy hill and continuing to slide backward.

“‘Yes, you can,’ I said, placing both my hands on her fulsome cheeks and pushing. She dissolved in laughter, managed two or three steps, and collapsed on the landing…A happy, giggly little girl.

“‘Come on in, baby.’”

Older women, such as Rita Hayworth at the end of her career struggling with memory problems and Dinah Shore tenderly putting up with his callow cockiness, were like Oedipal catnip to him. (Fortunately, he doesn’t bore us with the Freudian back story.) You might think a gentleman of Langella’s era (he’s 74) would be reluctant to kiss and tell, but the only woman in the book whose privacy he seems to want to protect is Jacqueline Kennedy. He does let on, however, that the two enjoyed a few “midnight swims” in Antigua, where they’d sit under the stars and leave each other love poetry in their adjoining rooms in Paul and Bunny Mellon’s guesthouse.

The subtitle of the book, “Famous Men and Women as I Knew Them,” stresses the subjective aspect of these profiles. These are photographs developed in Langella’s private darkroom. Sometimes the camera angle is just right, as when he captures President John F. Kennedybeing delighted by Noël Coward’s naughty humor at the Mellons’ Cape Cod manse. (What a boon to a young ambitious hobnobber, those Mellons were!) But often the interpretations he arrives at seem speculative to a fault. A chance run-in at a Sunset Boulevard hotel with a cantankerous Bette Davis at the end of her life doesn’t definitively back up the harsh assessment that she had “descended into the worst of her nature.”

Langella’s incisive comments on acting made me wish that he had focused “Dropped Names” exclusively on actors and their art. His savaging of Lee Strasberg and the Method, while highly personal, is informed by a lifetime of working in the theater. When he writes, in his profile of Anne Bancroft, that actors are “angry babies,” he speaks from personal experience and his remarks resonate. Langella suffers from the same “galloping narcissism” that he pins on his fellow performers. It’s an occupational hazard of being a star actor, even one whose name isn’t often dropped outside of Broadway circles. But not many of his peers could write such an eloquently dishy book.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.