Selling Stardom: A talent agent on Hollywood’s fringe, and a trail of unhappy clients

The top Hollywood talent agents have artwork by Annie Leibovitz and Ed Ruscha on their walls, armies of sharp young assistants at their beck and call, and Porsches gleaming in their parking garages.

Then there's Lynn Venturella.

She works out of an office with barred windows near homeless shanties and a medical marijuana dispensary in West L.A. There's no sign out front, no receptionist inside. On a recent visit, she sat behind a metal desk surrounded by cardboard boxes and empty five-gallon water bottles.

Venturella is one of the hundreds of talent agents operating on the fringes of Hollywood, where the clients are mostly character actors, fledgling screenwriters, workaday directors, even unknown wannabes.

Most provide a useful service, but complaints about abuses by second-tier talent representatives grew loud enough in 2009 to prod the state Legislature to pass the Krekorian Talent Scam Prevention Act, which prohibits agents and others who represent performers from charging them any fees other than commissions and reimbursements for some out-of-pocket costs.

Some of Venturella's former clients accuse her of pocketing fees they were owed for acting and modeling work, making promises she couldn't keep, pressing them into spending money and not acting in their best interest.

Public records show that Venturella or the agency she founded in 2009, the Pinkerton Model & Talent Co., have been sued in civil court at least 25 times, and at least 25 separate claims have been filed against her or Pinkerton in Small Claims Court. At least 20 of those cases ended with monetary judgments entered against Venturella or Pinkerton. Several others were dismissed, settled out of court or are pending. (Online records for some of the cases were incomplete or unavailable.)

Most of the cases involve small amounts of money. But in one legal dispute that is playing out in Los Angeles County Superior Court, a filing claims that Venturella was paid a $78,000 settlement that was intended for two of her clients, who say they never received payment. Venturella has not responded to the lawsuit.

Matt Whibley, the attorney for models Uliana Sivashova and Natalie White, says he hasn't been able to get law enforcement authorities to take an interest in the case. He and others contend that inexperienced actors and models are easy prey for unscrupulous agents, since prosecutors rarely take an interest in these cases and there usually isn't enough money at stake to entice civil lawyers.

Whibley said that because many of Venturella's former clients are transient Hollywood hopefuls with few resources, they aren't able to pursue the agent over alleged misdeeds.

“They can't afford a lawyer,” he said. “Economically, she is getting away with it.”

In an interview, Venturella, 61, declined to discuss specific complaints or clients. But in general, she acknowledged that she had at times taken money owed to some Pinkerton clients to pay the agency's debts.

“It went to lawyers' fees, it went to stay open, it went to pay people, it went to survive — to keep the agency going,” she said.

Venturella said she was once an aspiring actress herself, journeying from Newcastle, England, to the United States at age 18 to seek fame and fortune in show business.

She never found stardom, but she says the ill treatment she received at the hands of talent agents eventually led her to become one herself.

Aylya Marzolf

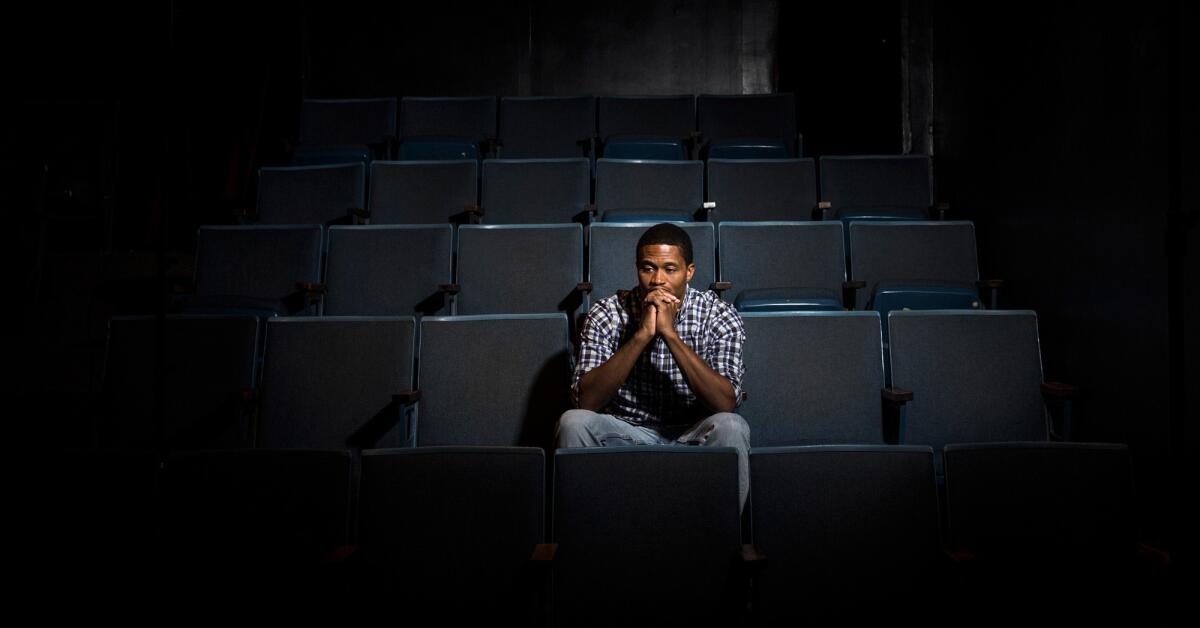

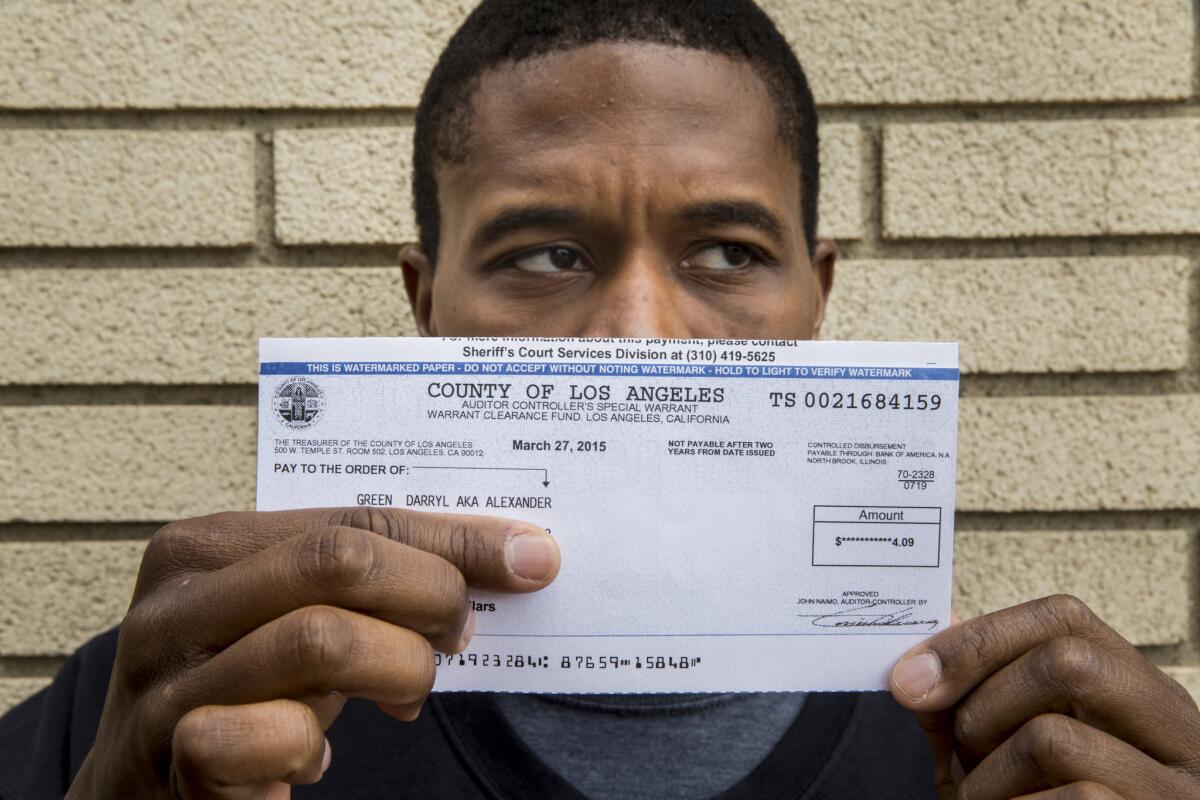

Darryl Green

“I wanted to be the kind of agent that I hadn't had. In the olden days the agents used to be really mean,” Venturella said. “I wanted to be a different type of agent.”

Whatever her intentions, she has left a long trail of unhappy former clients.

Aylya Marzolf, 28, of Panorama City said that Pinkerton succeeded in booking her in six TV spots and print ads for Apple, Adidas and other companies. She was supposed to be paid about $6,600. But Venturella kept the money, Marzolf said, forcing her to file a complaint with the California Labor Commissioner's Office. Eventually, Marzolf recouped what she was owed.

Actor Darryl Green said he was owed $640 for an auto dealership commercial that Venturella booked for him last year. Green, who works nights as a security guard, needed a root canal and was waiting on the check to pay for dental work. After months of trying to collect on it, the 36-year-old native of Columbus, S.C., sued the agency in Small Claims Court.

“It doesn't sound like a lot of money to the average person, but when you are a struggling actor, that's a big deal,” said Green, who goes by the stage name Spoon Alexander. He recovered only a fraction of the money. “Acting is a life of poverty. It is persistent poverty and inconsistent income.”

At the big agencies, talent agents typically find clients via referrals from their industry contacts, or by attending film festivals such as Sundance to spot up-and-comers in low-budget indie films. It's a different story lower down the ladder.

Small agencies post ads on the Internet and fliers in Hollywood photocopy shops. They prospect for clients at controversial talent conventions where hopefuls pay thousands of dollars to perform in front of industry professionals.

Attorneys point out that one source of trouble stems from the way performers are paid. When an actor books a job, the producer typically transfers the fee to the performer's agent — who holds it in a trust account and has 30 days to pay out the funds, minus a commission, which by state law cannot exceed 20%.

Sharon Faley-Harvey was leaving the Olive Garden in Burbank with her two young sons when a Pinkerton agent stopped them, raving about how cute her kids were.

The agent said she could get the boys in films, TV shows and commercials. Faley-Harvey, 33, decided to take a chance.

“I was really excited when we first got approached,” she said. “I have a friend whose daughter was on a sitcom for a few years and she's got a nice little college fund going.”

The agent, Corrina Lewis, said she worked for Pinkerton and was “street scouting.”

“This is something that we as agents do,” Lewis said. “You can be scouted in a mall, in a restaurant, on the side of the street, literally. It's common — it's part of our job.”

Street scouting is legal, but some performers say their agents have also pressured them into paying for photo shoots or acting lessons, which are sometimes offered by the agency itself or another company in which it has an economic interest — practices that could be prosecuted under the Krekorian Act.

After the encounter at the Olive Garden, Faley-Harvey said she agreed to come into the Pinkerton offices for a consultation with Venturella (Lewis had left the agency by then).

Faley-Harvey said that Venturella told her that her infant, Riley, needed head shots, and that she could offer “the least expensive” photographer for the job — her own daughter. Faley-Harvey paid $250 for pictures of Riley, who ended up doing a photo shoot for a Baby Gap print advertisement. But Pinkerton wouldn't pay the $450 fee he was due, she said.

She filed a complaint with the Better Business Bureau. In a response, Pinkerton acknowledged that Riley “did receive work,” and said it would investigate the claim of nonpayment and “take care of it, immediately, if we find there is money due.” A month later, Faley-Harvey filed a rebuttal saying that she still hadn't been paid. Pinkerton did not respond to that claim.

Uliana Sivashova

“It bothers me because it's his money and it's supposed to be in his bank account,” Faley-Harvey said. “I was going to put it all away for him for college.”

Venturella said that it remains her goal to pay back her former clients, the Faley-Harveys among them. “I will make sure Riley … [is] included in this,” Venturella said.

Venturella founded Pinkerton two years after a talent search company she started, Best New Talent, filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy protection. Several actors and models said they became clients of Pinkerton soon after it opened, when Venturella worked out of offices on the Sunset Strip that former client Marzolf said featured a balcony that afforded expansive views of the L.A. basin.

“It was clearly boutique, clearly professional,” Marzolf said.

There were other details that former clients said gave them confidence: The company's website said it had more than 700 clients and that Venturella “discovered and helped” actors who have appeared on TV shows including “ER” and films such as “Scream.”

And several past clients of Venturella said the fact that her agency was state-licensed — and maintained a required $50,000 bond — made them comfortable signing with it.

Green said that Pinkerton seemed to offer a shortcut to success after he moved to L.A. in 2012. After seeing the agency listed on the Screen Actors Guild website, he submitted his head shot. An agent quickly called him to set up a meeting. Soon he had signed a contract. “I said, ‘Yes,' being naive, not knowing,” he said.

Green sued Pinkerton in Small Claims Court last year after Venturella paid only a portion of what he was owed for the Cerritos Auto Square commercial. In December, a judge awarded him the remaining $440 plus court fees. In March, Green received a check for $4.09 — apparently all that authorities were able to collect from Pinkerton on his behalf.

He doesn't plan to cash the check. Instead, Green said, it will serve as a reminder of the perils of Hollywood. “The deck is definitely stacked against anyone who comes here,” he said.

Morgan Furtado, 14, of Tustin met a Pinkerton agent at a ProScout talent search event in 2012, said her mother, Michelle Furtado, who added that her daughter's red hair and olive skin made her a natural for the camera.

Pinkerton booked a car commercial for Morgan, but her mother said the promised $1,800 payment never arrived. “In the emails [Venturella] sent me, it's every excuse in the book as to why she hasn't sent the check — but she would say that it's about to be sent any day,” said the elder Furtado, a hairdresser.

She won a Small Claims Court case against Venturella in March but said she has still not been able to collect payment. Venturella said that she intends to pay back Morgan.

Marzolf, whose credits include the TV show “Victorious,” said she hired attorney Bryan Freedman after Venturella did not pay her roughly $6,600 she was due to receive for the six advertisements she shot. He took the case to the state Labor Commissioner's Office, which ruled in Marzolf's favor. In May, Pinkerton's $50,000 bond was used to pay what Marzolf was owed. The process took three years.

“Now I am more careful, more wary, less trusting,” she said.

Venturella said her money troubles began in 2012. At the time, she was courting a potential investor for Pinkerton, which is her maiden name. She said that she spent as much as $80,000 on her agency before the deal was finalized, and when it collapsed she was left foundering in debt.

Venturella, who also has had at least two personal bankruptcies and moved her agency's headquarters at least three times, said that much of her money has gone to “lawsuits and lawyers.”

By fall 2014, Pinkerton had parted ways with its remaining agents (it once had as many as 10), stopped taking on new business and did not renew its license, Venturella said. She said that she will refer anyone with a “real claim” against Pinkerton to its bonding agency, and noted that Small Claims Court also is an option.

During an in-person interview, Venturella vacillated between contrition and jocularity. At one point, she said she would only discuss her clients in detail if a reporter agreed to coauthor a book with her that she'd title “Bad Agent.”

“I would make it more juicy than it actually is,” Venturella said. “I would like it to be more fiction. I'd make the bad worse.”

But a few moments later, when asked about clients' lawsuits and the money they were owed, she turned tearful.

“I know I've ended up hurting some people — I didn't mean to,” Venturella said, starting to cry. “It's not who I am — I am not a bad person.”

Pinkerton ceased operating by Jan. 1, Venturella said, and she spent part of this year “closing things up.”

A new talent agency, Impression Entertainment Group, has since opened up shop in Pinkerton's former digs on Cotner Avenue in West L.A. And Venturella, who still has an office in the suite, said that she is a consultant to Impression.

Venturella said that she does not have an economic interest in the new agency, but the company represents some of her former clients. The founder and chief executive of Impression, Johanna Keogh, did not respond to requests for comment.

The Impression office buzzed with activity during a recent visit. Just outside of Venturella's shabby office, two secretaries answered a flurry of phone calls.

Nearby, an agent perched at the edge of a couch, telling a young man how he could jump-start his career, painting visions of stardom for another Hollywood hopeful.

One in a series of articles about selling stardom in Hollywood.

Additional Credits: Video: Robert Meeks and Jay L. Clendenin. Research: Scott Wilson. Digital design: Lily Mihalik. Digital producer: Evan Wagstaff. Lead photo caption: Actor Darryl Green is photographed at the Playhouse West theater in North Hollywood.

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.