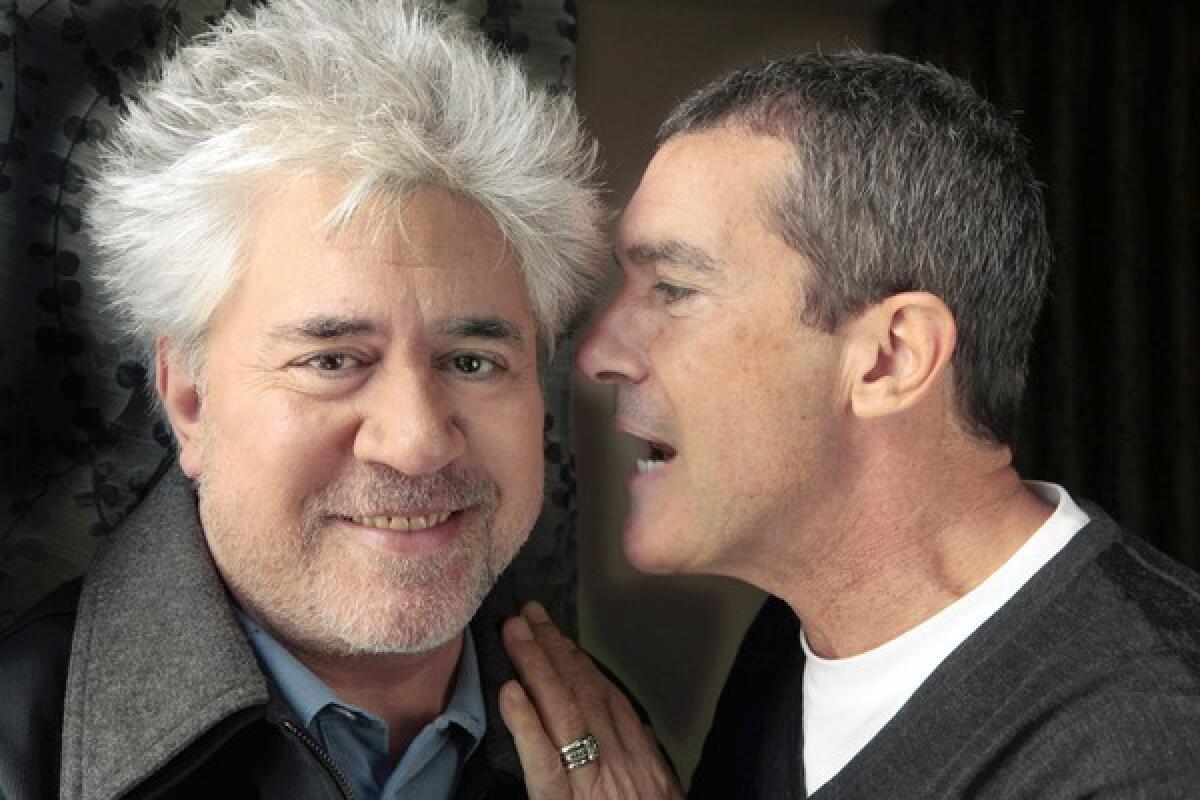

Antonio Banderas, Pedro Almodovar on friendship and film

In the 25 years since he started making movies with Pedro Almodóvar, Antonio Banderas says one thing hasn’t changed: The iconoclastic director is still leading Banderas toward the edge of the creative abyss. And he is still diving in.

“Basically what you have to do with Pedro Almodóvar is take a leap of faith as an actor,” Banderas said recently, settling into a sofa after a cigarette break in a Beverly Hills hotel suite. “Sometimes you’re working with him and you feel like he’s pushing you to a cliff. And he says, ‘Jump!’ And you say, ‘But Pedro, I’m going to kill myself.’ ‘Jump! You have to trust me!’”

Banderas’ blind-faith meter must have been soaring when he and Almodóvar reunited to make “The Skin I Live In,” a Hitchcockian hybrid of thriller, melodrama and horror film that opens Friday. It’s the two Spaniards’ first collaboration since Banderas costarred with Victoria Abril in “Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!” (1990), playing an escaped psychiatric patient who kidnaps an actress in hopes of making her fall in love with him.

In “The Skin I Live In,” Banderas portrays an even more complex and diabolical control freak, a plastic surgeon named Robert Ledgard who is haunted by a tragic past. For reasons that become clear only later, the rich, handsome doctor is keeping a beautiful young woman, Vera (Elena Anaya), captive in the fortress-like home he shares with his sinister housekeeper, Marilia (Marisa Paredes, another of Almodóvar’s longtime accomplices).

Clad in a flesh-colored body stocking and kept under constant camera surveillance while she sleeps, eats and practices yoga, Vera harbors a secret that can’t be breached by the doctor’s gleaming knives. Slicing and splicing multiple ideas and emotions, “The Skin I Live In” is an Almodóvarian blend of kink, exuberance, sly cultural allusions and questions about human identity.

Although Banderas, 51, now lives in the United States, while Almodóvar, 62, resides in Madrid, the two have kept in close contact and see each other intermittently.

Banderas said the director first approached him about making the film a decade ago, at Cannes, after Almodóvar had bought the rights to the story, which is based on a novel, “Tarantula,” by the French crime writer Thierry Jonquet.

Both men got sidetracked on other projects. Then a couple of years ago, Almodóvar called Banderas, told him, “It’s time!” and sent him the script.

“I read it,” Banderas recalled, “and I said, Oh … I’m in trouble! Sacred trouble!”

For Banderas, working with Almodóvar again after years playing caped crusaders (“The Mask of Zorro”) and cartoon cats (“Puss in Boots”) in Hollywood was like re-confronting himself as performer, flayed to his essence. “It was an amazing re-encounter on many different levels, the personal level of course and the professional level too,” he said.

“When you go to Almodóvar, if the bag is filled with accumulated experiences with other directors and other movies and other stuff — tricks — he doesn’t like that. He opens the bag, looks at it, closes it again and throws it out, and says, ‘No, we’re going to start as we used to work, Antonio, in the ‘80s, from zero. And zero is a very uncomfortable place, I know, because you’re going to have fears.’”

The director concurred that his reunion with Banderas, who first attracted Hollywood’s attention after starring in Almodóvar films such as “Matador” (1986), “Law of Desire” (1987) and “Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown” (1988) was long overdue. “It was a very satisfying experience,” he said by phone, “because we recuperated each other as friends, and as director and actor.”

“The Skin I Live In” was shot in Spain and was the first Spanish-language lead role for the Málaga-born actor in many years. “So it was a very powerful re-encounter with his own culture,” Almodóvar said. “And it was very emotional for me to see what Antonio felt for this re-encounter, this return to his roots.”

When the two men last worked together two decades ago, Spain still was reveling in the all-night party atmosphere that followed the collapse of the Franco dictatorship.

Banderas, already a star in Europe, was on the verge of a nervy breakout role in Hollywood, playing the lover of Tom Hanks’ AIDS-stricken character in “Philadelphia.”

Almodóvar was pushing Spanish cinema in directions unfamiliar since the heyday of Luis Buñuel, disrupting the status quo with frank depictions of same-sex love, twisted family relationships, bizarre obsessions and sudden outbursts of shocking violence. But not everyone was enamored of the brash young auteur.

“It was enormously difficult to obtain money for a film with these characteristics, with this theme,” the director recalled. “We say that we lived during an incredible explosion of liberty, enjoying the new democracy. But nonetheless it was very hard to find money to produce my movies. Nowadays I don’t have this difficulty.”

Banderas said that working on movies like “Law of Desire” and dealing with the subsequent outrage voiced by critics and clerics over its moral values helped “liberate” him personally from guilt instilled by his Roman Catholic upbringing.

“I owe Pedro more than professional issues. I owe Pedro a way of thinking, a way of understanding life, looking at a life without fear,” he said. “He’s not only a movie director for me. He’s a real friend, almost like a brother and a person that I respect, admire and that profoundly, deeply, I love.”

Perhaps the biggest difference between the past and present, Almodóvar said, is that the pair no longer spend their off-camera hours indulging in youthful pleasures. Banderas is a confirmed family man who hangs out with his wife, actress Melanie Griffith, and children. The director practices meditation and yoga to limber up after long hours of writing.

“My life is very based in my work. I have to take care of myself,” Almodóvar said, laughing. “So the life we share in 2011 is, we say, the opposite of what we led in the ‘80s.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.