Library of Congress builds the record collection of the century

Reporting from Culpeper, Va. — About an hour south of Washington, D.C., deep beneath rolling hills near the verdant Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia, lies a storehouse filled with bounty.

At one time, during the Cold War, that treasure was cash — about $3-billion worth — that the Federal Reserve had socked away inside cinderblock bunkers built to keep an accessible, safe stash of funds in case of nuclear attack.

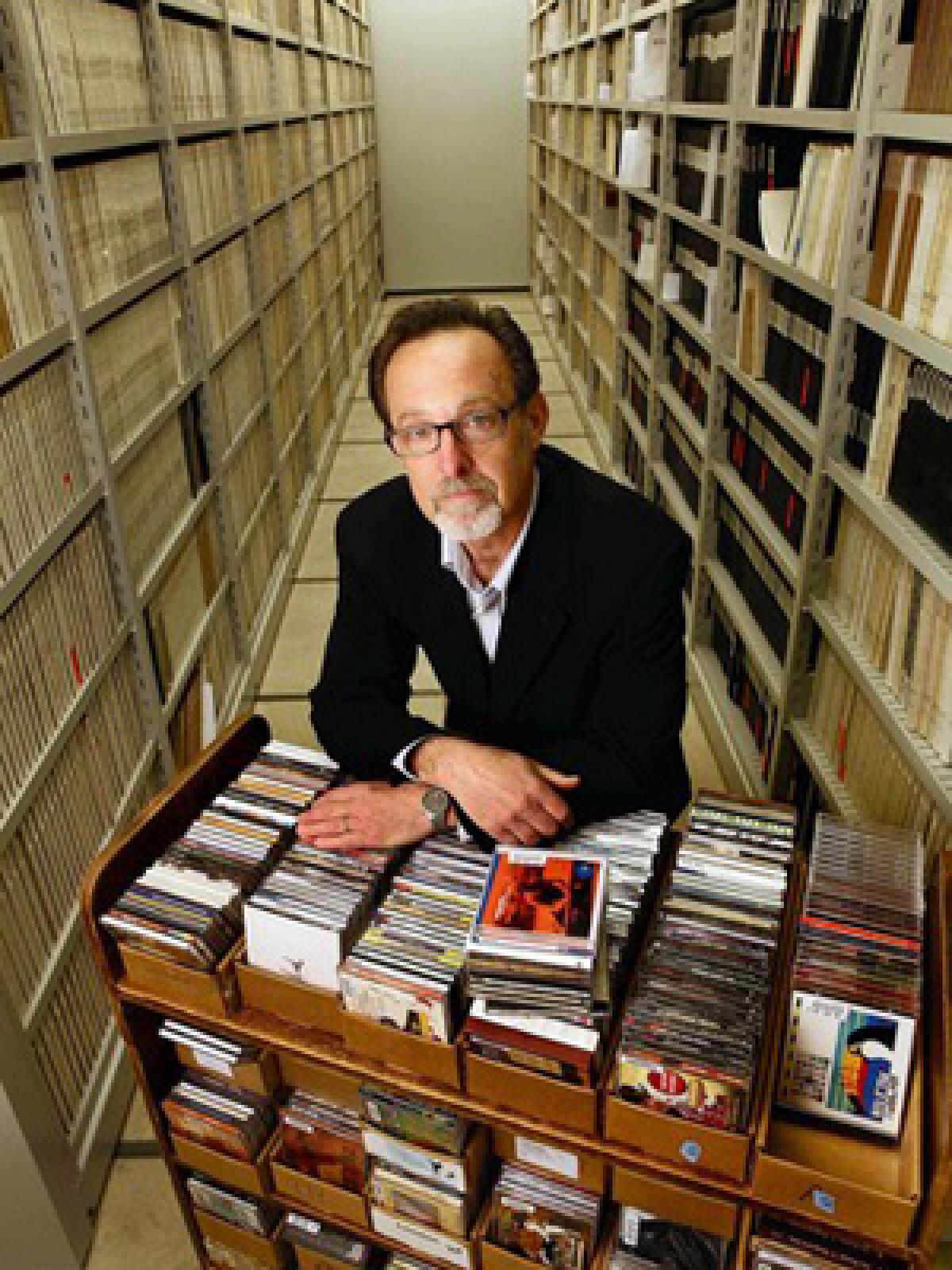

Photos: America’s record stash

Now what’s buried here, however, is cultural rather than financial: The bunkers are a repository containing nearly 100 miles of shelves stacked with some 6 million items: reels of film; kinescopes; videotape and screenplays; magnetic audiotape; wax cylinders; shellac, metal and vinyl discs; wire recordings; paper piano rolls; photographs; manuscripts; and other materials. In short, a century’s worth of the nation’s musical and cinematic legacy.

This is the Library of Congress’ $250-million Packard Campus for Audio-Visual Conservation, a 45-acre vault and state-of-the-art preservation and restoration facility on Virginia’s Mt. Pony. It’s here that a recent donation from Universal Music Group, nearly a quarter-million master recordings by musicians including Duke Ellington, Billie Holiday and Bing Crosby, is now permanently housed. Some staff members busy themselves daily cleaning and gluing fragile 100-year-old films back together; others meticulously vacuum dust from the grooves of ancient 78 rpm discs, which are washed before being transferred to digital files that can be accessed by scholars, musicologists, journalists, filmmakers, musicians and other visitors.

As part of the Library of Congress, this trove is available to anyone, free. But because of the complexities of copyright law, access is restricted to the library’s reading rooms in Washington and Culpeper. Library officials, however, are poised to unveil a new program that will significantly expand public access to a big chunk of the library’s goods, even if it won’t provide carte blanche availability to everything stored there. A news conference is scheduled for Tuesday to announce the details.

The library’s main storage facility induces a chill, literally: It’s kept at 50 degrees and 35% relative humidity to prevent materials from degrading. It’s even frostier at the opposite end of the property in the vault for volatile nitrate film, which is cooled to 35 degrees.

The long hallway also can spark images of the closing scene in “Raiders of the Lost Ark,” although it’s not a single airplane hangar-sized room full of crates packed with who-knows-what treasures. Instead, the second-floor hallway leads past 17 vaults, each of which yields shelf after shelf filled with platters of vinyl, shellac or wax or magnetic tape in various formats: open reel as well as audiocassettes, four- and eight-track tape cartridges and digital audiotapes. There also are a good number of vintage wax cylinders as well as metal master discs.

The breadth of the library’s stock is impossible to summarize. But in addition to copies of every published recording registered for protection in recent decades with the U.S. Copyright Office, the library has acquired personal collections from classical music giants such as Leonard Bernstein, composer Aaron Copland and pianist Wanda Landowska, in some cases including never-released test pressings, as well as every 78 rpm disc recorded by jazz titan Jelly Roll Morton.

It possesses tens of thousands of lacquer discs from NBC Radio, including the network’s complete archive of World War II coverage; documentarian Tony Schwartz’s trove of audio recordings from the streets of New York; and half a million LPs, among which are dozens of surf and hot-rod music-themed discs that Capitol Records issued in the ‘60s to capitalize on those crazes, including “Hot Rod Hootenanny” by Mr. Gasser & the Weirdos, with cover art and songs co-written by fabled car designer Ed “Big Daddy” Roth.

The sound vault is so extensive that when Universal Music Group’s gift was announced, Gene DeAnna, who heads the recorded sound section, didn’t bat an eye. The new donation, which takes up a mile of linear shelving space, is one of the largest single gifts to the library ever. But it represents only about a 1% expansion of the audio collection, which typically grows by 120,000 to 150,000 items per year, about two-thirds of which is sound recordings. And within are essential recordings of the American experience.

When producers at Sony Music’s Legacy division were working on the new box set “Robert Johnson: The Complete Recordings: The Centennial Edition,” for example, they tapped the library for some metal masters and shellac discs that were better than what the label had in its own archive.

But records and tapes aren’t the only musical recordings here. Preservation specialist Larry Miller pulled out some rare wax cylinders about 4 inches in diameter, much larger and thicker than the standard 2-inch cylinders that proliferated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries until flat discs took over.

“Back in those days, there were patent wars,” Miller said. “Everyone was trying to not pay money to someone else for use of a particular format.” Like the Beta-VHS videotape wars in the ‘70s and ‘80s, or the Blu-ray versus HD-DVD battles more recently. “It was a higher fidelity version and had longer playing time too,” DeAnna said. “It was kind of like the Blu-ray of its day.”

Universal’s donation upped the total 2010 acquisition for the recorded sound division to more than 300,000 items. The final truckload of recordings that had long been housed in Universal’s vault in Pennsylvania was scheduled to arrive in Culpeper on Wednesday.

The question is how many people will have access to it.

Beyond the library’s mission of physical conservation and restoration of its vast archive, providing public access to it is both a driving goal and key hurdle these days. Physically converting aging films or recordings to contemporary playback media is a breeze compared with navigating the copyright clearances that would permit broad access.

It’s a byproduct of copyright law, which characteristically lags several steps behind changes in technology. This reality is particularly challenging when it comes to music: Although music compositions have been under the purview of federal copyright law since 1831, sound recordings didn’t get that protection until 1972. Before that, ownership of recordings was determined by state and common law — something the 1972 federal law didn’t change.

And there’s the rub for DeAnna. The shift to digital technology that makes streaming access possible will inevitably push the boundaries of current copyright law. Deanna added that, if nothing else, academia should have access to the music.

“We should be able to have Internet streaming access on secure sites — and more than one, not just our reading room,” he said. “We should have partnerships with universities around the country — we should have at least that” ability to allow researchers and students remote use of the library’s materials.

Matthew Barton, the recorded sound section curator, points out: “Anything else from before 1923 — a book, a movie, a published song, sheet music — is public domain now.” Not so for the music in that same time period, and as a result, many recordings, even those that have been digitized, can’t legally travel beyond the library’s walls unless a morass of ownership issues can be unraveled. “The whole idea of copyright,” DeAnna said, “is that eventually it does become public domain.”

DeAnna points to so-called orphan works, for which the rights holders are not readily identifiable, as evidence of the confusion. A prime example is the Savory Collection of nearly 1,000 live recordings made by recording engineer William Savory in the late ‘30s, discs now residing with the National Jazz Museum in Harlem. They encompass previously unknown extended performances by such musical luminaries captured in their prime as Ellington, Holiday, Louis Armstrong, Benny Goodman, Judy Garland, Artie Shaw and Chick Webb.

Museum director Loren Schoenberg said, “My goal is to have all of it, every last second of it, available on the Internet. If it was up to me, I’d just throw it on the Internet, let everybody sue each other and happy new year. But you can’t do that, because you’re dealing with [musicians’] estates, labels, record companies and publishers.”

A proposal that Congress bring all pre-1972 sound recordings under federal copyright law is in the public comments stage.

“There’s a considerable body of sound that could come under orphan work legislation if it was controlled by federal copyright law,” DeAnna said.

“It seems to me not to have worked taking all this century’s sound recordings off of our soundscape,” DeAnna said.

Indeed, according to a 2005 survey conducted for the library’s National Recording Preservation Board, of 1,521 recordings made from 1890 to 1964, only 14% has been made available to the public.

Before the Packard Campus was built, the Library of Congress’ collection was scattered among seven storage sites across four states and the District of Columbia.

But in 1997, Congress approved a public-private partnership that, in exchange for an initial $10-million grant, transferred the former Federal Reserve facility, which had been decommissioned four years earlier, to the Packard Humanities Institute, a private organization spearheaded by David Woodley Packard, the son of Hewlett-Packard cofounder David Packard.

Upon completion of the $150-million construction project, Packard donated the buildings back to the Library of Congress in July 2007, making it the largest private gift to the U.S. legislative branch and one of the largest ever to the federal government.

Congress has kicked in about $90 million for equipment, staffing and other costs of opening and operating the facility, which consists of four main components: the three-story conservation building with staff offices and film and audio preservation labs; two underground vaults for safety film, video, sound recordings and nitrate films; and a central plant that houses equipment to maintain temperature and humidity in the vaults.

Members of the public can listen to virtually anything from the audio collection already converted to a digital file on demand at the library’s offices on Capitol Hill.

Whether a curious researcher will actually be able to play back what’s stored in the vaults depends not only on copyright law, though, but also on the format.

“I love to give the example that the cylinder from 1900 may be easier to play back than the DAT [digital audiotape] from 2001,” sound curator Barton said. “Seriously. There are a lot of DATs that just won’t play now.”

Photos: America’s record stash

The most enduring formats? Not CDs or MP3 digital files.

“Vinyl discs properly stored will last hundreds of years,” Miller said. “Shellac too.”

Producer T Bone Burnett, a vocal champion of analog vinyl over digital audio, visited the library not long ago to discuss the issue. “He testified in front of us and said, ‘I would encourage the Library of Congress to preserve to vinyl,’” DeAnna recalled. “We all kind of leaned forward, and my colleague said, ‘So, Mr. Burnett are you preserving your own collection to vinyl?’ He said, ‘Nah, I’m doing all digital.’”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.