From the Archives: 40-year-old George Lucas interview predicts ‘Star Wars’’ future with Disney

Before the first-ever “Star Wars” premiered on screens across America, Los Angeles Times writer Paul Rosenfield sat down with the creator of a galaxy far, far away. Then 33, George Lucas was just a few days shy from the release of his “space opera,” prophetically claiming that “Star Wars” was the movie he thinks “Disney would have made when Walt Disney was alive.” Who knew decades later the droids and the mouse would reside in the same castle. This story was originally published on June 5, 1977, and titled, “Lucas: Film-Maker With the Force.”

George Lucas was talking reel-to-reel. It had been a hard day’s night of sound-mixing at Goldwyn Studios. Five days before the openings of “Star Wars” and — gadzooks! — there was not yet an answer print. The writer-director-wizard was sharing the facilities with another hyphenate, Martin Scorsese (“New York, New York”). Both facing oncoming release dates, the men were responsible for a cumulative of $21 million in product.

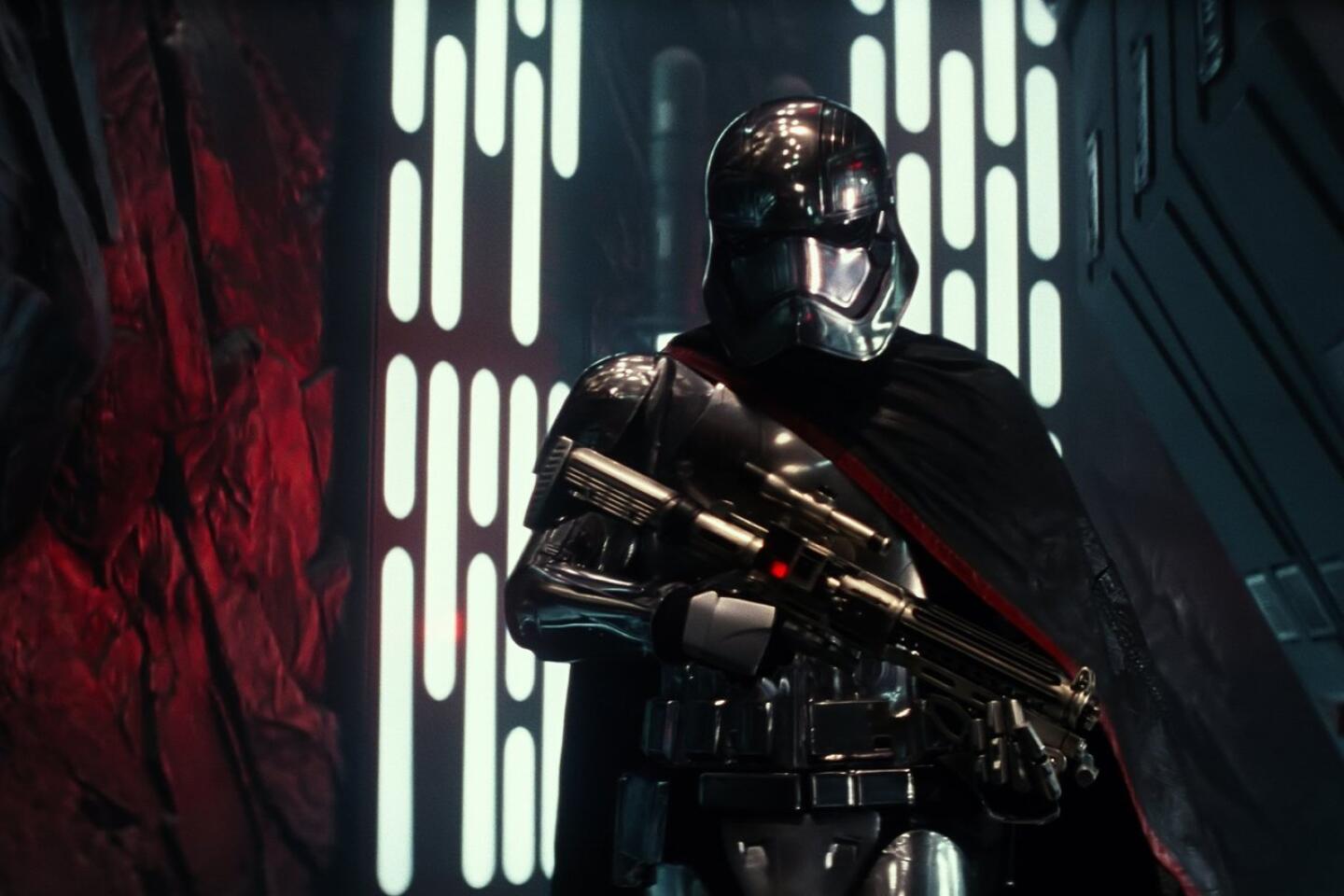

FULL COVERAGE: ‘Star Wars: Episode VII - The Force Awakens’

Lucas had the night shift — 8 p.m. to 8 a.m. By day, he was in a Hollywood lab. Marcia Lucas, editor of both films and George’s wife, remained calm. “Can we meet for breakfast?” she asked her husband.

For George Lucas, 33, the hype was about to happen. In the works was a Time magazine cover story, an incalculable profit and prestige boost for any film. (Remember “Love Story”?) Lucas would have been the first of the new tribe of directors to be so singled out. The Israeli election of Menachem Begin forced a last-minute switch in the magazine’s front page plans. Lucas expressed no chagrin.

The quiet craftsman isn’t apparently much into the print media. He claims neither to read nor admire critics. “And mostly I don’t do interviews,” he said early on what would be a late night. Though cordial, during the film’s early promo-push Lucas saw only three publications: The Times — L.A. and N.Y. — and Time. And possibly only the last because “Star Wars” publicists smelled a cover.

In person he’s no self-promoter: Robert Altman in reverse. His horn at least doesn’t blow at midnight. “I never bank on anything. I think this movie will break even.”

And then some. Box-office records in the first release week were set in 43 — out of 43 — theaters, according to Fox VP Ashley Boone. The seven-day gross: $2.89 million. By June 1, company stock rose from 11 1/2, the previous week’s high, to 18.

Hourly figures were phoned in from Manhattan. In San Francisco, box lunches were sold to queued crowds. In Westwood, a section of Wilshire was littered with falafel wrappers — and lined with ticket holders. The all-time Hollywood Boulevard record set by “The Godfather” was broken. And George Lucas was in Hawaii.

“The ball is back in the studio’s court,” said the bearded, slightly built filmmaker on his six-year project. (The movie is only Lucas’ third feature: “American Graffiti” followed the non-cultish “THX-1138.”) “I’ve given this my best shot. We’re off to the sun.”

**

Luke Skywalker, the Lucas-like hero in “Star Wars,” left more than his uncle’s moisture farm on the arid planet of Tatooine. He’s also headed for America’s merchandise marts. “In a way this film was designed around toys,” Lucas says, lighting up at the subject. He may look like a brooding scientist, but the man is boyish, on one subject at least. “I actually make toys. I’m not making much for directing this movie. If I make money, it will be from the toys.”

Et cetera. Upcoming are Marvel comic books, inflatable laser swords, miniature ape-like Wookiees, T-shirts, a gilded C-3PO (the movie’s homage to the Tin Man), computer games, posters, a mock-up Imperial Death Star spaceship, and Obi-Wan, perhaps the first-ever senior-citizen doll. The goodies are due at counters this summer.

“I don’t consider it cashing in, but I have invested in a toy company operation. Also, we’ll be involved with the largest toy company in the world. This could be very large.”

“I think of this as a movie Disney would have made when Walt Disney was alive.” Chatting while watching rushes, Lucas feels the need to explain. “I call it ‘space opera.’ That’s a genre that’s been around a long time, in the books of Burroughs and Heinlein, but never really done on film.

“What I attempted was science fiction without the science. I wanted an engaging Saturday matinee movie, but not camp or parody. And not a heavy intellectual trip like ‘2001.’ Think of this as ‘The Sting’ in outer space.”

Lucas had been urged after “Graffiti” to tackle something deep. Instead he went for what he wanted: pure entertainment. “ ‘THX’ was my 20-year-old consciousness; I used my head as a filmmaker. ‘Graffiti’ was me at 16 using my heart. This movie was using my hands, at 12.

“I wanted a contemporary version of the myth and the fairy tale. Storytelling has always been about the faraway. The Victorian era had the exotic East. In early America, there was the lure of the West. It was savage. Until about 20 years ago we believed we could go to Treasure Island.

“There’s a whole generation today with a great need for fantasy. The Lone Ranger and Long John Silver. ‘Star Wars’ is hopefully a feeble attempt to make up for that lack, without goriness or violence.

“It’s a hard genre to pull off. Enchanted forests are over the hill. Also, I wanted to show the importance of friendship. Two males who don’t hate each other, who don’t go off blowing up stadiums.”

A Super Bowl heist would surely have been easier than the Lucas undertaking. “I was very broke after ‘Graffiti,’” the director said, when asked about the genesis of “Star Wars.” “I’d spent four and a half years trying to get ‘Apocalypse Now’ off the ground. At that time nobody would do that movie and nobody wanted to do this movie.” A 12-page outline of “Star Wars” was turned down by both United Artists and Universal.

“Finally Fox offered a little development money, very little. Our original budget was $18 million, which we scaled down to $14 million. Then we got it down to a bare $8.5 million. The studio said $7.5, and we said, ‘We’ll do it.’ Gary Kurtz [Lucas’ producing-partner] and I figured somehow we’d get the extra money.”

As budgets go, this one went eventually to $9.5 million. A bargain among this summer’s releases. “We’re the rock-bottom,” claims Lucas. “ ‘The Deep’ is $14 million. ‘A Bridge Too Far’ is $22 million. And Francis [Coppola], who finally did ‘Apocalypse Now’ [of which Lucas is part owner], will come in at $25 million.

**

Last week, Fox President Alan Ladd Jr., overseer of “Star Wars,” recalled his struggles in getting the studio go-ahead:

“How do you do a synopsis of this movie for a board of directors? Imagine saying, ‘There is a Wookiee named Chewbacca and …’ The company was going through a bad period anyway. [Fox Chairman] Dennis Stanfill decided to go with it, and then fortunately didn’t ask a lot of questions.

“For four years George and I have been talking — though he and I together don’t make one-half an extrovert — and only a week before release did I see the film. The humanity is what makes it. All I can say is that the man got a performance out of a robot.”

Somehow. “There is no magic in moviemaking,” says the director who masterminded 363 special effects. He’s admittedly now weary. “What’s there has to be there.” Unlike many of the film generation of whom he is the current wunderkind, Lucas isn’t over-zealous about moviemaking.

“I see the whole process as war: money and energy and hurt feelings. Say some poor clown has to fall out of a 10-story building. What if he dies?”

Sums up ace editor and Universal VP Verna Fields (“Jaws, “American Graffiti”), “George is a sufferer.”

“I consider this my professional movie debut,” Lucas says, without pomp. “Star Wars” took 18 months of shooting in Tunisia, England, Guatemala and Death Valley, among other sites. “What it means is you have to act like a corporation president.

“In the old days, if the horses weren’t there, you’d call Jack Warner and yell, ‘Why the hell aren’t the horses here?’ Now you do your own yelling and hiring and firing. I had to build my own studio, render the storyboards, devise the opticals. And I poured a lot of my own money in.

“I don’t like always to be angry, and on this I was a lot. The crew did not always do things as well as I would have liked. You go around disgusted and give up being a free person — that’s what directing a major movie is like.”

Steve Spielberg, Lucas’ friend and director of “Jaws,” remarked recently, “Oh, he complains. But look at the results. George ran down ‘Graffiti’ too. Before I’d seen it, he said, ‘Forgive me. This is my tribute to Sam Katzman [B picture producer, things like “How to Get a College Girl”].’ I went in expecting a turkey. But every one of George’s films are incredibly enjoyable—and personal.”

**

If moviemaking is the work of a single person, as Orson Welles claimed, how does the singular Lucas see the finished product?

“You’d better like your own movies. You have to look at every frame 300-400 times. You can really suffer. Fortunately, I haven’t made anything yet I couldn’t sit through. But, no, you never deliver your vision.”

“Francis [Coppola] says on ‘Apocalypse’ that he at last has learned to do the Big Movie. He says he now sees how it can go all the way through to the other side. Before, he always suffered and went crazy. Like we all do.”

Painter (his oils are reminiscent of Keane, yet original), furniture builder, owner of a sci-fi shop in New York, Lucas is as adept with cars as with cameras. “I don’t know if even he knows where his talent comes from,” Verna Fields says. Others, lately, think that they know. In a rush to fill in blanks, rumorists offer Welles-like misconceptions. For example, they say the Lucases live in “A modest San Anselmo cottage.” Wrong.

They live in a black-shingled house, minutes from the Golden Gate bridge. It actually is a ministudio, complete with editing and screening rooms— and a 78 rpm jukebox.

Lucas claims he never was a movie buff: “As a kid [in Modesto, the site of “Graffiti”] I only went to movies to chase girls. I was totally into cars. Anyway, it took years before good movies got to my town. And foreign films — never.”

“I wanted to go to art school, but my father would only send me to a real university.” Cinematographer Haskell Wexler, for whom Lucas built a race car, steered him to USC. “I was interested in photography, so the only thing to major in was cinema. Suddenly I was turned on to this whole amazing new world.

“Everybody there wanted to direct. But I learned editing and camera work.”

SIGN UP for the free Classic Hollywood newsletter >>

Soon he was making movies for the U.S. Information Agency. Among the film students hired there by Verna Fields were Lucas and his future wife. “George was almost fired,” Fields recalls. “He kept falling asleep at the Moviola. Then we realized he was working on ‘THX’ at night. We all thought he was terribly slow. But, yes, the talent was recognized very early.”

**

“Star Wars: The Force Awakens” Press Conference Videos

Video: 'Star Wars: The Force Awakens' video 2

Video: 'Star Wars: The Force Awakens' video 1

Video: 'Star Wars: The Force Awakens' video 3

'Star Wars: The Force Awakens' Video 7

Video: 'Star Wars: The Force Awakens' - Part 2, video 1

Video: 'Star Wars: The Force Awakens' - Part 2, video 2

Video: 'Star Wars: The Force Awakens' - Part 2, video 4

'Star Wars: The Force Awakens' Part 2 Video 7

Video: 'Star Wars: The Force Awakens' video 4

'Star Wars: The Force Awakens' Part 2 Video 6

Lucas began his association with Coppola on the ill-fated “Rain People.” With some backing from Warners, the teaming led to the San Francisco-based American Zoetrope, an ambitious film factory. When both “THX” and “Rain People” flopped at Warners, the backing came undone. The friendship remained. Later, Coppola used his bankability to help get “Graffiti” made.

“The way I make movies I learned from Francis,” Lucas says. “I was his right hand for 10 years. I absorbed his idiosyncrasies. Yet we’re exact opposites, 180 degrees apart; as a result, we’re each other’s foil. You need that in this business.”

Still headquartered at Zoetrope, the men are part of a tribe of Marin County filmmakers that includes John Korty, Philip Kaufman and Michael Ritchie. Though there are other hints, a line in “Star Wars” lingers: “Sand People ride single file.” One is led to believe Lucas is a loner. Wrong again.

These filmmakers are indeed united artists, sharing ideas and sometimes percentage points. Cronyism? “That’s always been around,” Lucas says defensively. “I’ve lived in San Francisco for 10 years. I’ve spent six weeks in L.A. mixing this film. I’d never mixed a film here before. I doubt I’ll do it again.

“There’s this thing of wanting people to fail here. I’m not into all that. I wanted to see if I could do an epic adventure, and I did it. I found directing — as opposed to filmmaking — 50% business and 50% being a psychiatrist. That doesn’t leave much time for film. So I’m retiring from this world.

“The system here requires large budgets. I’m cheap about films. I’ve always tried to make them for as little as possible. I hate to waste money; I don’t spent it lightly,” says the man who was made a millionaire by “Graffiti.”

That film was the 11th largest grosser ever. “Star Wars” should put Lucas in the Top 10.

**

“What do I want do do? Underground films. I want to help my friends. And I’ll executive-produce to make a living.” Lucas seems to mean it. “If there’s a recurrent theme in my work it’s about taking responsibility. We really make our own cages. I call it ‘simplistic positivism.’ But the point is, it’s me.”

He claims he won’t direct the “Star Wars” sequels himself. “There should be at least three or four, but I won’t direct them. I made the prototype. I’ll not do that again. Let others interpret it their own way…

“I really want to go back to film school. I started out working with my hands, making cabinets, making films. I want to get back to that. Filmmaking is an art, like any other, no greater or less. But it’s a crazy art.

“Or maybe I’ll get my master’s in anthropology. That’s what movies are about anyway. Cultural imprints. Visual explorations. There are ways of evoking images that haven’t been done yet. I want to make films I don’t have to finish.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.