Tonys 2015: ‘Curious Incident of the Dog’ brings ‘autistic perspective to life’

Reporting from New York — Priscilla Gilman is the mother of an autistic son and the author of a book about her experience, “The Anti-Romantic Child: A Story of Unexpected Joy.” The Times asked her to attend a performance of “The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time” at the Barrymore Theatre and write about the play from her perspective. “Curious Incident,” based on the novel by Mark Haddon, is nominated for six Tony Awards at Sunday’s ceremony, including one for actor Alex Sharp, who plays Christopher, the play’s autistic hero.

Did I feel awe at the spectacular staging, admiration for the performances, or pleased with the subtle intelligence of “The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time”? Absolutely. But first I was filled with gratitude.

I’m the mother of an autistic teenage boy, Benj, who, like Christopher Boone, the play’s protagonist, is a math whiz and a Sherlock Holmes fan. Since the publication of my memoir, I’ve become an advocate for autistic people. There are aspects of “Curious Incident” that fall back on cliché — that autistic people lack empathy, for example — but the play wonderfully brings the autistic perspective to life.

FULL COVERAGE: Tony Awards 2015

The entire production is an enormous act of imaginative empathy with an autistic person. The set, a huge three-sided black box with surfaces lined like graph paper, makes Christopher’s mind visual, illustrating the interiority of an otherwise hidden mode of consciousness. The letters and numbers, words and phrases that fill and overfill Christopher’s thoughts and sight are projected, often at dizzying speed, onto the walls. It’s like watching a movie of the character’s turbulent stream of consciousness.

When Christopher is overloaded or in distress, music pulses and blares, sound effects ring out and lights flash. Idioms and metaphors appear onstage in bizarrely literal form: a woman speaking of “the apple of my eye” has a piece of fruit on her face.

ESSENTIAL ARTS & CULTURE NEWSLETTER >> Get great stories delivered to your inbox

We experience the deluge with Christopher. And we can understand Christopher because we can see what he senses. The intensely “auto” world of autistic disconnection has been transformed into an experience that all can share.

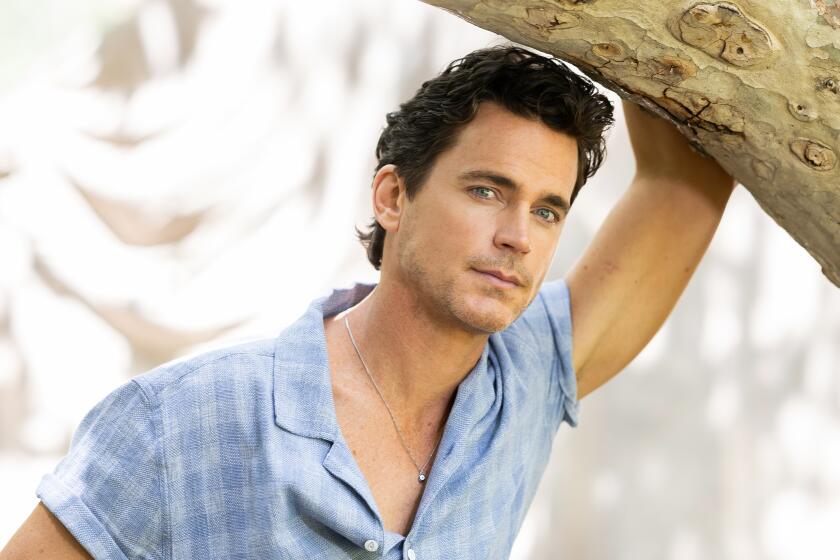

As brought to life by the remarkable actor Alex Sharp, Christopher Boone’s behavior, thoughts and experience were deeply familiar to me. His stilted speech and cognitive inflexibility, his counting and drumming as self-soothing mechanisms, his need for predictability and clarity are my son Benj to a T. Some of his behaviors, however, are things that have subsided or softened in Benj over time.

Seeing Christopher with his hands over his ears, resisting his parents’ affectionate overtures, flying into a panic at a strange sound or an unexpected touch, I kept thinking: This is what Benj was like when he was 3, 4, 5 years old. His melting down, flinging himself to the ground, shaking in overstimulation, screaming — the play brought back just how difficult it once was to cope with Benj’s intense anxiety. It also made me newly grateful for just how far Benj has come. Grateful for all the therapists and teachers who helped — not to change him, not to cure him, but to calm his reactivity so his gifts could flourish.

Similarly, the play doesn’t try to “normalize” Christopher. He’s a hero, but an autistic hero. He achieves what he does in large part because of the qualities inherent in his autism: his extraordinary memory and attention to detail, his obsessiveness, his insistence on honesty. Additionally, he’s not only a remarkable logician but also a dreamer, a romantic with a great capacity for wonder, awe and joy.

For all its pyrotechnical splendor, one of the play’s most valuable aspects is its most practical. It vividly depicts the usual unhelpful ways of treating autistic children: talking down to them, assuming they can’t understand, dismissing them as too much trouble, touching them without their permission, screaming at them, not making allowances for the gaps in their understanding of body language, social cues and figurative language.

Characters who unfairly berate, grossly underestimate or haplessly misunderstand Christopher are given their comeuppance. We see the better path by contrast: focusing on strengths and affinities, offering patient, calm coaching and mantras that can be used in especially difficult situations, respecting wishes and honoring interests.

The final thing I was grateful for in the play was, perhaps surprisingly, the way it ended. In the book, we are left with Christopher’s list of goals — to attend college and do spectacularly well, live independently, “become a scientist” — and then an affirmation of infinite possibility:

And I know I can do this because I solved the mystery of who killed Wellington and I found my mother and I was brave and I wrote a book and that means I can do anything.

The play alters this by introducing doubt, by making the future wildly provisional. After the same list of dreams, rather than simply asserting his freedom, Christopher poses it as a question to his teacher, Siobhan:

Does that mean I can do anything, do you think? Does that mean I can do anything, Siobhan? Does that mean I can do anything?

Siobhan never answers. The stage goes dark.

The play does not abandon the autistic perspective; incessant questioning and repetition are hallmarks of autistic speech. With this suggestively unanswered question, the play resists a simple, sentimental optimism about Christopher’s future and reminds us of the obstacles the world can still throw up. That little truth-telling moment made me want to pump my fist because — yes! — autistic people are complicated, capable of compassion, full of boundless possibility. And — yes! — many autistic people face serious challenges in getting to the point of being able to function happily and productively. Both sides must be acknowledged.

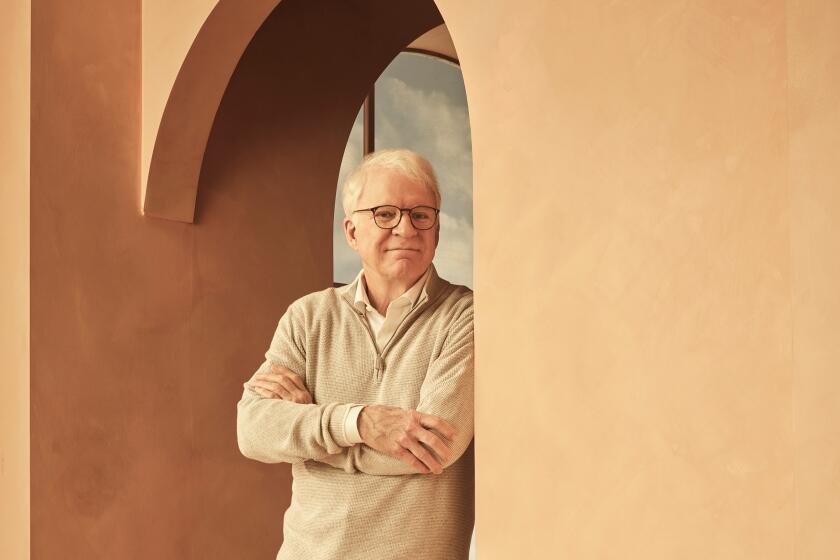

The success of boys like Christopher and Benj, of course, depends on acts of generosity and compassionate understanding of the kind that the play has itself been performing. After the lights come up and the bows have been taken, Alex Sharp as Christopher returns to the stage and presides over it in an exuberant coda. Like a madcap professor or ebullient magician, he bounds around explaining how he solved a math problem, then gleefully calls for confetti, which rains down upon the wildly applauding theater-goers.

I think the play has an almost unprecedented potential to educate people about both the struggles and the gifts of the autistic mind and to change the way we relate to, think about and value autistic people. My hope and belief is that people will be galvanized by “Curious Incident” to make visions like Christopher’s possible in the real world. A teacher who sees it might vow to differentiate instruction, a business owner to hire someone on the autistic spectrum, a college administrator to create better transition and support services.

Though Christopher’s revels are ended, his story is “such stuff / As dreams are made on.”

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.