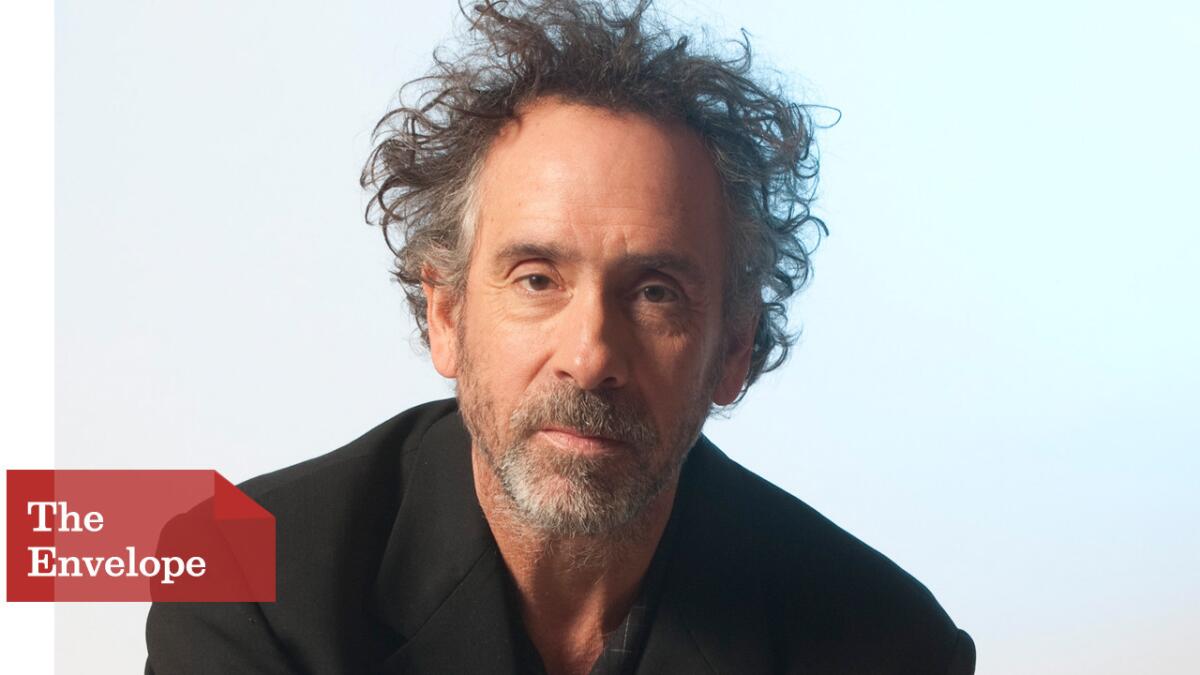

The Envelope: ‘Big Eyes’ director Tim Burton draws praise for tale of pop art and ego

In the annals of true-life weird tales, few are stranger than the saga of Margaret and Walter Keane. In the 1960s, the couple rocketed to Pop art celebrity as Walter gained fame for the mass-produced images of melancholy children gazing out at the world through doleful, oversized eyes. In truth, the work was Margaret’s, and after a decade of reluctantly watching her husband take credit for her art, she finally spoke out.

The dispute ended up in court, with a judge supplying paints to both parties and instructing them to produce a completed canvas in one hour. Despite Margaret’s victory in the proceedings, Walter continued to claim that he was the true artist.

“Even after the story came out, it still flew under the radar,” says Tim Burton, whose new film, “Big Eyes,” due for release Dec. 25, recounts this chapter in the Keanes’ lives and casts Amy Adams and Christoph Waltz as the warring couple.

“It’s a quietly complicated story, which I found interesting. I just imagine her going along with it and getting trapped in this weird world. Then, also keeping that kind of secret and knowing the work’s getting this polarization of opinion — some people loved it and some people violently wanted to rip them off the walls — I liked all that.”

Burton, of course, knows a thing or two about making popular, if not always acclaimed, art. Movies including “Batman,” “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory” and “Alice in Wonderland” enjoyed outsized success at the box office. “Alice,” the lavish 2010 fairy tale, for example, earned more than $1 billion in receipts worldwide. His stop-motion brainchild “The Nightmare Before Christmas,” which he produced but did not direct, has become a holiday perennial and a merchandising cash cow for Disney.

With “Big Eyes,” though, Burton is mining the same cultural territory that brought him his greatest critical success. Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski, the screenwriting duo who penned Burton’s Oscar-winning 1994 Hollywood biopic, “Ed Wood,” wrote the new film, and both projects shed new light on divisive midcentury cultural figures whose artistic contributions are considered suspect, if not plainly dreadful.

Early reviews have hailed “Big Eyes” as Burton’s best movie in years, with Adams and Waltz tipped as front-runners for acting nominations. (“Ed Wood” won Academy Awards for its makeup and for Martin Landau’s supporting performance as horror icon Bela Lugosi.)

Alexander and Karaszewski stumbled onto the Keane story 11 years ago while working on a science-fiction comedy and searching for examples of pop culture kitsch with the power to destroy an alien civilization. They arranged a meeting with Margaret, who at the time was 75, and persuaded her to grant them permission to bring her life to the screen.

They spent the better part of a decade attempting to secure independent financing and a cast with an eye toward directing the movie themselves, but when Waltz expressed interest in playing charismatic huckster Walter early last year — Adams came aboard a short time later — the screenwriters decided to hand the project off to Burton, who previously had planned to produce the movie.

Opening in San Francisco in 1958, “Big Eyes” trades the black-and-white imagery of Burton’s earlier character study for the candy-colored climes of the North Beach neighborhood, where Margaret lands with her daughter, Jane, after fleeing an unhappy first marriage. She meets Walter at an outdoor art fair, where he charms her with exotic tales of studying painting in France. Following a whirlwind courtship, the two quickly wed.

After he strikes a deal with the proprietor of the Hungry i nightclub to display their work, Walter is surprised to see Margaret’s paintings attract interest over his own, and a misunderstanding on the part of a buyer leads to his claiming authorship over the work. As the portraits of the morose children gain widespread popularity outside the art world establishment, Walter persuades Margaret to allow him to continue to take the credit, assuring her that people aren’t interested in “women’s art” and it’s better for both of them for her to remain complicit in the lie.

“It’s kind of like ‘Invasion of the Body Snatchers’ emotionally,” Burton observes.

While shooting the film last summer in Vancouver, Canada — the production traveled to San Francisco only briefly for a few key scenes — Burton worked closely with Adams and Waltz to ensure that Margaret and Walter’s screen dynamic was never reduced to victim and villain. Walter’s desperate need to attain status and adoration for a talent he doesn’t possess makes him something of a tragic figure; Margaret’s self-sacrifice belies an internal strength that ultimately prompts her to speak out.

“You try to actually feel the different characters,” Burton says. “There were aspects of Amy’s character that I really could identify with, and unfortunately, certain aspects of Walter I could identify with. It’s an interesting dynamic.”

Now 87, Margaret Keane leads a quiet life in Northern California, and while Burton has commissioned two paintings from the artist, he describes her as “very private” and notes that the release of the film would certainly prompt her to revisit the bizarre circumstances of her career and the emotional trauma of her difficult marriage to Walter, who died in 2000. “It must be really weird for her, given the type of person she is,” he says.

But “Big Eyes” also could serve as another kind of mainstream vindication, a vehicle to tell Margaret’s unusual story to the masses even if her work, those curious children with the saucer eyes, remains its own kind of popular oddity.

“I’m fascinated by the response, that polarization of things is always interesting to me,” Burton says. “I think that’s why that work sort of remains popular, why other artists knock it off and do variations on it. … There’s a weird power to it whether you like it or not.”

Twitter: @ginamcLAT

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.