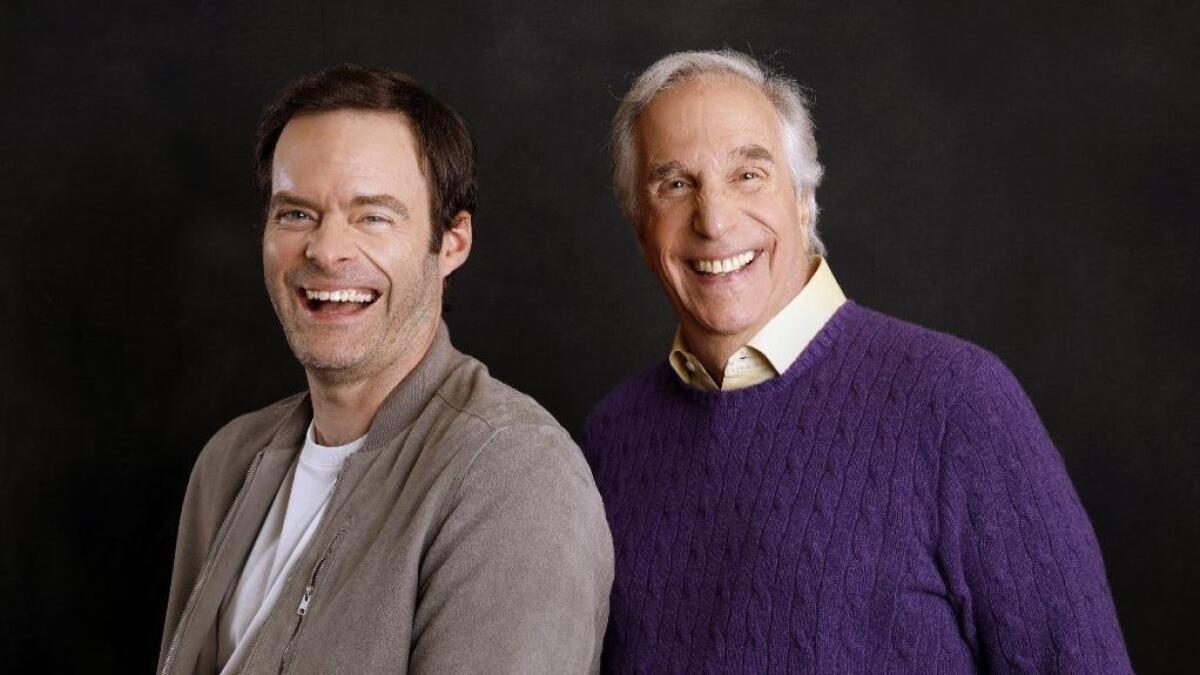

Bill Hader and Henry Winkler root ‘Barry’ in friendship, collaboration and some hero worship

Meeting Henry Winkler for the first time, Bill Hader remembers, was like coming face to face with Mickey Mouse or Big Bird, mythical characters from the earliest memories of his childhood.

Casting his HBO series, “Barry,” Hader had asked the network if Winkler might be available for the part of a vain acting teacher. “Actually, he’s coming in to read,” they told him. And soon afterward, Winkler, the man Hader spent hours watching on “Happy Days” as a kid, arrived and picked up a script, and all Hader could do was think, “Oh, my God. I’m acting with Henry Winkler.”

“We were all scared and nervous in the room,” Hader says, between bites of a lunch salad as Winkler listens, clearly enjoying the story. “Terrified, really. As kids, we all wanted to be Fonzie. Then later, I remember staying up and watching ‘Night Shift’ when I wasn’t supposed to and seeing Henry and thinking, ‘Wait. That’s the guy who plays Fonzie? Oh, so that’s what an actor does?’ Do you know what I mean? That’s the thing that broke it for me.”

Flash-forward to the Emmys last September. “Barry,” a dark comedy about a hit man desperate to change and leave his profession, has been nominated for 13 trophies. The night’s first award goes to Winkler, who exhales deeply, wraps Hader in a bear hug and kisses the show’s co-creator Alec Berg, before bounding to the stage. Later, Hader wins for his lead turn, an outcome he didn’t expect and can only process by saying, “Wow.” (“We were still celebrating Henry,” Hader says. “I thought Donald Glover or Ted Danson would win.”)

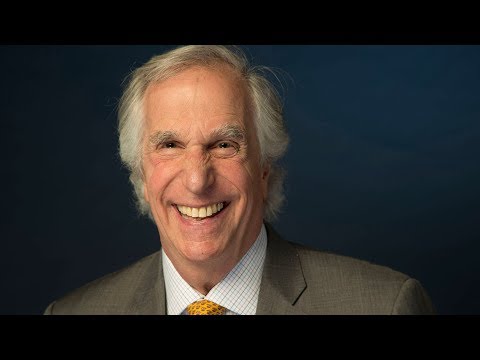

Reflecting on that evening as well as their careers, Winkler, 73, offers a word he believes links him and Hader. Tenacity.

“We know what we want and never let it go,” Winkler says.

After his 11-season run on “Happy Days” ended in 1984, Winkler says he couldn’t get a decent acting job for seven years. (“No one would hire me,” he says. “People would say, ‘Oh, he is so talented – and funny! But he’s the Fonz.’ ”)

Hader too struggled to reinvent himself after deciding to leave “Saturday Night Live” in 2013 after eight years of expert mimicry and memorable characters.

“The main piece of advice people would give me was: ‘Do a Stefon movie,’” Hader says, referring to his popular “SNL” character who’d offer eclectic tips for things to do in New York. “Don’t get me wrong. I love Stefon. I’ll always love Stefon. But if I wanted to keep playing him, I would have stayed on the show.”

That these two talented actors found each other and wound up collaborating is an example of what Winkler calls life’s circles. He finds them everywhere. Winkler’s son, Max, went to film school at USC with Hiro Murai, the celebrated director who has helmed several “Barry” episodes. “Barry” is filmed on the same Sony Studios sound stage as “Happy Days,” which Winkler had never told Hader until just before he delivered his last line of this second season.

“You hang around long enough, there are a lot of circles,” Winkler says. (One more Winkler likes to note: He was 27 when he got the role of the Fonz and 72 when he won the Emmy. “I’ve flipped the numbers, and I am closer to the actor that I thought about being when I was 27.”)

Winkler and Hader have become friends as well as collaborators, the tone being set from the moment of their first meeting. Hader and Berg had initially written acting teacher Gene Cousineau as an arch, John Barrymore type — a fallen star, a shameless ham (he wore a cape). Winkler brought a vulnerability to his reading, turning the character from a self-absorbed monster into a failed actor still out there trying to make it. When he left, Hader turned to Berg and said, “He just made the part better.” And then they looked at other characters. Had they made them too big as well?

“We didn’t know the tone of the show until Henry read,” Hader says.

“I’m glad I’m here having lunch with you and hearing this,” Winkler says, his comic timing forever perfect.

“Barry’s” second season burrows into the central question of the series and, really, of life itself: Can people transform their natures or are they born a certain way, fated to remain the same until death?

Hader’s Barry wants to stop killing. He longs to believe that he is not a murderer, that circumstances have forced him to do terrible things. One of the father figures in his life, Cousineau, tells him he can change. The other father figure, Stephen Root’s manipulative handler Monroe Fuches, advises Barry to keep killing. It’s who he is. It’s what he does best.

The season’s battle between determinism and free will is laid bare during a fourth episode scene between Hader and Winkler in which Barry confides in Cousineau, confessing something horrible he did as a Marine in Afghanistan. Hader and Berg were rewriting the dialogue right up until they filmed it because if it didn’t work, Hader says, the “season would have been in trouble.” And then Hader and Winkler kept rehearsing it and refining it, ultimately landing in a gut-wrenching place that expresses cautious hope for Barry’s humanity.

“We’re comfortable with each other and we’re friends, so it’s nice when you’re trying to figure out a thing together and you feel like, ‘Oh, I can just do that and Henry will know what to do,’ ” Hader says.

“That is the truth,” Winkler adds. “We have gotten to a place that, wherever one of us is, the other is there.”

Another thing that hasn’t changed since the moment they met is the joy Winkler derives from making Hader laugh. “He is the best audience,” Winkler says. “To make him dissolve into laughter is one of the great compliments ever.”

Winkler fishes for that response even when they’re not on set. Throughout lunch, Winkler can’t help but perform for Hader, pausing a story about how he was never much good at performing Shakespeare by voicing his regret about the coconut shrimp he’s eating. (“My kingdom for a toothpick!”)

When Hader relates how meditation helped him ease his anxiety during his later years on “Saturday Night Live,” Winkler relates: “I get nervous when I’m driving to work and I’m thinking, ‘Do I know what I’m doing? Do I know how to do this?’ And once I arrive on set, I have a breakfast burrito — which is one of the reasons I became an actor — [Hader is losing it] and now I’m thinking, ‘Oh, my God, I now look heavy.’ And then I just go to work and somehow it turns out OK.”

Small wonder then that when Hader is asked if Winkler’s character will return for the show’s third season (“That’s a great question … can we both ask that,” Winkler says, leaning forward with a flourish), Hader emphatically answers, “Yes! Yes! There’s no way Henry’s not going to be back. Are you kidding me?”

Well … Hader and Berg have shown a willingness to follow the story where it leads on “Barry” — even if that results in characters dying, which is a natural development in a series centered on a hit man. “Don’t you think that I don’t think about that every minute?” Winkler says, his eyes widening.

“It’s funny,” Hader says. “People love Henry so much. When I’m out on the street, people approach me and say, ‘Oh, my God, “Barry!” What’s it like to work with Henry Winkler?’ What would I say to those people if we killed him off? I don’t think people would find any kind of apology acceptable.”

Winkler smiles. “You know when you’re walking through an airport and people talk to you about what you’re doing right now instead of what you’ve done in the past?” he says. “That’s when you know you’re in it to win it. Men my age are waiting for the phone to ring — or putting the phone away. And here we are. It’s thrilling.”

Twitter: @glennwhipp

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.