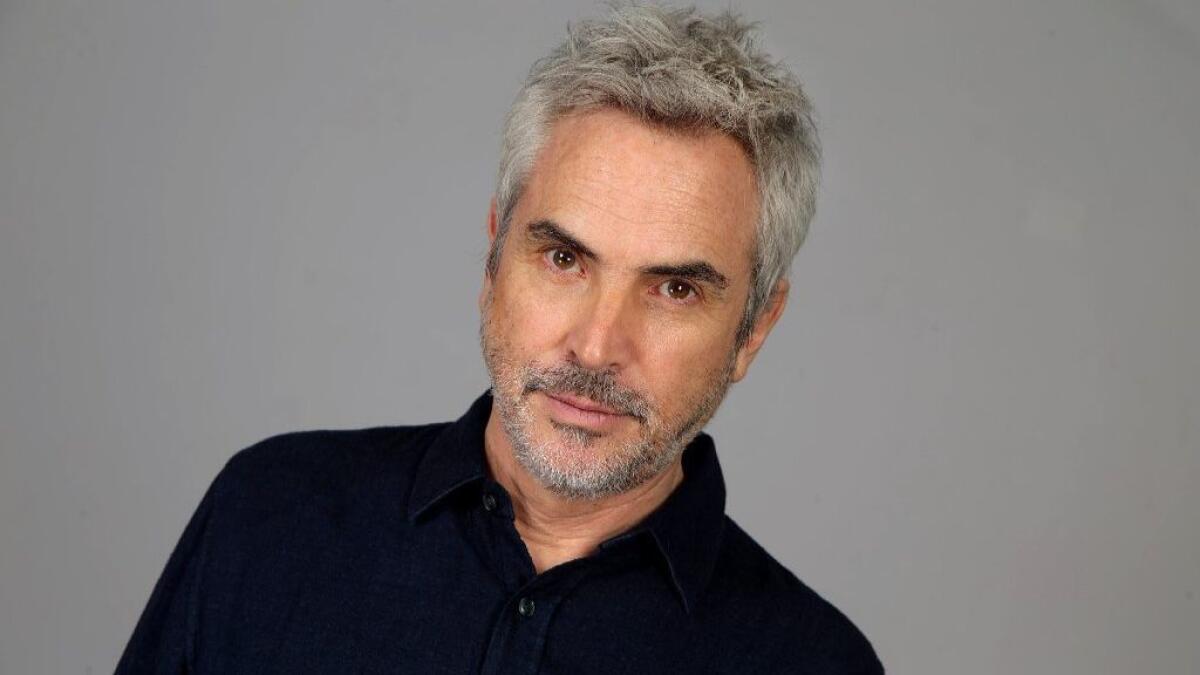

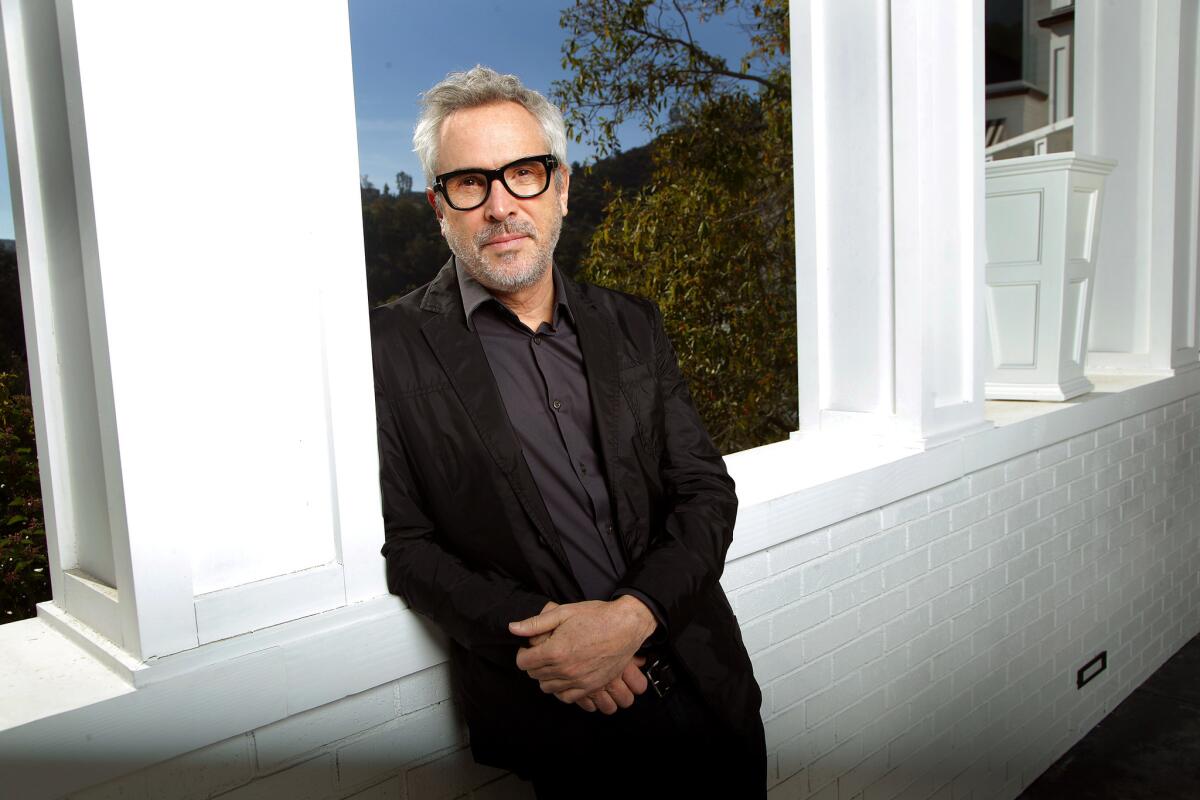

Alfonso Cuarón reveals the hidden layers of ‘Roma’

If you haven’t yet seen “Roma,” it’s not what you think. Or not just what you think.

American audiences inured to big-budget spectacles might look at this intensely personal story of a domestic worker’s day-to-day life in 1970s Mexico City (in black and white, in Spanish) and build a kind of wall of low cinematic expectations around it. In reality, Alfonso Cuarón’s finely detailed tribute to one of the women who raised him is one of his most ambitious works, is secretly high-tech, and ponders nothing less than the mysteries of love itself.

“Besides being one of the people I have loved most in my life, in many ways, her journey amplifies a lot of the complexities of Mexico as a society and, in my point of view, humanity at large,” says the writer-director-producer-cinematographer-editor.

“On one hand, there’s the perverse relationship between social class and ethnic background. In Mexico, the whiter you are, the better the possibilities — socially and economically — you’re going to be more privileged. You go down to the indigenous communities, and they live in very tough conditions and are oppressed. On top of that, she’s a woman; that adds another vulnerability in the social hierarchy.”

That context shapes “Roma,” which earned 10 Oscar nominations, including best picture and director, but Cuarón is after something even more essential.

“All of that is a social frame for something that I find more mysterious for existence at large, which is how people come together,” says Cuarón. “Time and space completely constrain who we are. But those two things create the possibility of bonds of affection.”

The gravity among people

“Roma’s” indigenous domestic-worker protagonist Cleo, played by newcomer Yalitza Aparicio, is based on the real-life woman Cuarón calls only Libo.

“I have two women who raised me — my mother and Libo, who is almost like my mother. I come from a sheltered, middle-class background. She comes from a completely different background. How do those things come together?

“There’s only one thing that can give meaning to this senseless existence: those bonds of affection. It’s as if we live a life of shared loneliness, in which only those bonds can give any comfort.”

Cuarón speaks existentially about the randomness of life, the luck of the draw that dropped Libo into his family, the transience of it all. Perhaps, thanks to “Roma,” Libo has attained a kind of immortality. To that, he laughs and says, “But for how long?” He says the same when considering the immortality of Shakespeare’s works: “Yes, but for how long?” The sun, says the director of “Gravity,” will eventually expand and perhaps all humanity will end. “This isn’t a downer, by the way,” he adds. “That’s why I find it so beautiful, those bonds of affection. Sometimes they can be poisonous as well. But they make you who you are.”

He is, in fact, smiling most of the time as he ponders the death of the sun, eyes sparkling, offering some of the tea he’s fixing in this room at the Chateau Marmont.

FULL COVERAGE: Get the latest on awards season from The Envelope »

“For me, Libo made a difference in my life. So maybe what gives meaning is people who made a difference in your life and hopefully you make a difference in theirs.”

The filmmaker and his secondary mother are still very close, he says.

“A neighbor usually comes and gives her the newspaper articles that are about me. She just keeps them there for me. I say,” he relays this with a hint of affectionate embarrassment, “ ‘You don’t need to keep them.’ But she puts them there for whenever I go.”

That closeness made it possible for the filmmaker to research as he did. He asked her about minutiae, such as whether she would linger in bed after her alarm went off or get straight up, as well as touchier subjects, such as her pregnancy by the boyfriend who winds up an abusive cad. Cuarón says the film is 90% from reality, but its absurd naked martial-arts demonstration by that young man is of the other 10%.

The filmmaker was concerned when she told him, “ ‘There’s only one thing that I don’t like … Why you have to put that boy naked there?’ ”

Cuarón laughs heartily, with affection.

Memory plays tricks, and so does post

Cuarón was meticulous about recreating the atmosphere of the Colonia Roma neighborhood of Mexico City at the turn of the 1970s.

“I’m getting to an age, probably, where sometimes I don’t remember what I did last week. But I have always had a very good memory about my childhood and part of my teen years,” says the 57-year-old. “Memory is the ultimate liar as well. The only way you access a memory is from the standpoint of the present. That present rewrites everything in an unconscious way. Accessing that memory is a door that leads to this endless corridor of doors, and you keep on opening doors.

“Smells, flavors, sounds, they trigger memories. All cities have their own musicality.” He rattles off aspects of the soundscape of Los Angeles — some audible within this West Hollywood hotel room — including loud music from passing cars and the constant hum of activity.

“In Mexico City, you have always dogs barking. Airplanes passing. Besides the traffic, street vendors. The garbage collector is this guy with a bell passing by. The sweet potatoes cart: There’s this steam pipe, this whistle. The sharpener still is the flute. The ragman had a very specific call, but now it’s a recorded call in a loudspeaker. So the thing was to find older ragmen to sing the chant.”

He says he often was set off by his senses in the process.

“There’s a particular smell of rain falling down — not in nature, but on pavement, especially on particular kinds of tile. Immediately it triggers memories of that house. I had it when we were doing the scene when the kids were picking up the hail. Wow. The tiles, getting wet and getting all that smell. My God. You get really transported.”

The production went to great lengths to cinematically immerse viewers in that world. Cuarón happily asserts that “Roma” is “not low-tech. Probably this is the most complex Dolby Atmos mix that has ever been done.”

And suddenly, the director of the famously accurate sci-fi adventure “Gravity” and the grittily dystopian “Children of Men” is back in the room.

“The amount of information in our files, I think it’s six times bigger than any Dolby Atmos mix that had been done before. I think our process of visual post-production — the color correction and stuff — is probably one of the longest processes that Technicolor has ever done. Even the visual effects — those who’ve seen the film, prepare to have your minds blown, probably 98% of the shots have a visual effect.”

The recurring character gets the spotlight

“Roma” is actually Libo’s second appearance of sorts in Cuarón’s filmography.

“In ‘Y Tu Mamà Tambien,’ she plays the nanny of Diego Luna,” he says of her cameo appearance. “The phone is ringing; Diego Luna is watching TV and she comes to pick up the phone next to him. He cannot pick up the phone. That was her. And then they’re driving on the road, they pass in front of the town where [her character] was born. ‘He called her “Mom” until he was 7 years old,’ the voiceover said. That was about Libo.

“She’s very, very touched and very happy that I dedicated [‘Roma’] to her,” he says. “At the same time, I kept inviting her to events; she didn’t want to go. She went to New York, to the film festival. She said, ‘You’re going to be there? Then I go because otherwise I never see you.’

“She is family. When you talk about her, it’s just like talking about my mom.”

He says racist and classist abuse directed at domestic workers in Mexico was common when he was growing up. “I had no tolerance for that. Because of Libo. All these racist kinds of jokes about indigenous people, I could … not … stand. You’re talking about my mom.”

He says she has seen “Roma” “two or three times and she always cries a lot. But she doesn’t cry about her circumstance; she cries because she’s concerned about the children.”

Cuarón chuckles and adds, “The only thing she says is ‘I hope the guy’ — you know, the guy who impregnates her — ‘I hope he sees the film.’ ”

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.