TIFF 2014: John Cusack and Paul Dano channel a Brian Wilson melody

Reporting from Toronto — There are few genres that get filmmakers more excited, and audiences more bored, than the music biopic. Oft-trod, easily misbegotten, it’s a form that can even turn sane filmmaking heads into concrete--and movies into VH1-ified examinations of talented people who rise, fall and learn some lessons along the way.

So it’s a refreshing surprise to find “Love & Mercy,” a story about the pop icon Brian Wilson from two ends of his life, break the mold and even invigorate the form.

Written by Oren Moverman (“The Messenger,” “I’m Not There”) and directed by the producer-financier Bill Pohlad, “Love” eschews the easy flashback or frame story in favor of a dual-tiered approach. One story line has us following a young Wilson (Paul Dano) in 1960s Southern California as he seeks to push the Beach Boys away from the surf-pop of their early years in more experimental direction, not exactly to the satisfaction of his bandmates. Creative genius and tensions with those close to him grow in tandem, and even as Wilson is making some of the best music of his life, that life is unraveling.

The second story line, circa the late 1980s, finds us with an older Wilson (Cusack), hollowed-out and under the control of Eugene Landy (Paul Giamatti), a doctor who pulled him from his depression but now exerts a Svengali-like power over him, keeping close watch over his charge and dosing him with drugs. Wilson is essentially a prisoner in his own home, unable to take a step without the intimidations of Landy or one of his henchmen.

Into this mix — at car dealership, of all places — comes Melinda Ledbetter (Elizabeth Banks), a confident former model who now hawks Cadillacs, one of which Wilson has shown up to buy. She is intrigued by the musician but also mystified by his Stockholm syndrome.

“He’s manipulating you,” she soon tells him of Landy. “He’s protecting me,” Wilson replies. “You’re protecting him,” Ledbetter returns. Against Landy’s wishes, a romance flowers.

Pohlad tells each storyline chronologically but cuts back and forth between them, so that we are essentially watching a successful young Wilson coming undone (and inventing bold new music) at the same time as we are watching an older, fractured Wilson trying to put himself back together.

“If it was just telling young Brian’s story about the music I don’t know that I would have done it,” Pohlad said in an interview Monday at a restaurant at the Toronto International Film Festival, where his movie world-premiered to a strongly enthusiastic response Sunday night. “But there were a lot of different levels besides that. On another level it’s about creative genius vs. madness. And it’s also a story of how this woman pulled Brian Wilson out of a deep hole.”

Pohlad was inspired to make the movie by two elements, he said: the 1997 box set of “Pet Sounds” that offers illuminating detail about how the music for the seminal album was put together, and his hearing about the car-dealership moment in which Wilson and Ledbetter (the two are now married) met.

Pohlad took a long-extant script called “Heroes and Villains” and set out having Moverman, who has taken on unconventional music stories before in the Bob Dylan pic “I’m Not There,” write a new draft. Pohlad also set out to get permission from Ledbetter and Wilson, who were initially skeptical of any filmic take on their lives — Wilson, after all, isn’t exactly in his best state for many of the events chronicled here.

In addition to its structural ingenuity, the film is eager to show how the music was actually made. Pohlad often shoots the studio scenes of the young Wilson in documentary style, hiring real musicians so he can show the creative process as it’s rarely seen on screen. Instruments and arrangements come together in Wilson’s bursts of inspiration for albums such as “Pet Sounds” and the unfinished material that would eventually come to be released as “The Smile Sessions.”

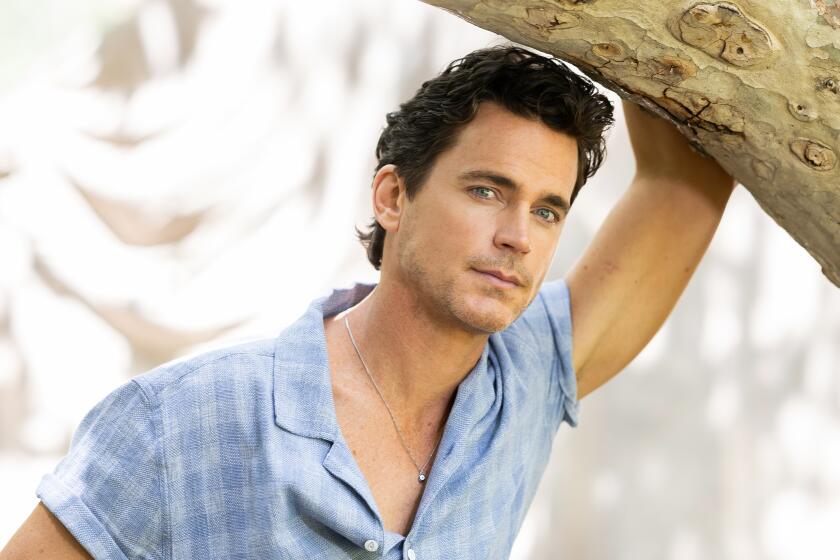

The film, which does not have a U.S. distributor but has attracted substantial buyer interest since its premiere at the festival, also offers the prospect of actors at the top of their game. Dano suggests a man whose genius does fierce battle with his other instincts, while even in Wilson’s beaten-down state Cusack avoids a mopey victim and goes for something edgier and funnier, his spaciness undercut with comedy.

“In a way that is Brian,” Cusack said in an interview about the role. “He does have all of that. The broadband is not slow. But I think sometimes with geniuses it’s hard to avoid these obsessive tendencies. They can’t get the song out of their heads.”

Cusack, who with movies like “High Fidelity” and “Say Anything” is often associated with music on film, said he hopes “Love & Mercy” (the title comes from Wilson’s 1988 solo album) underscores just how much the artist provides a soundtrack even to modern life.

“It’s hard to overestimate his influence on music,” Cusack said. “Pet Sounds was a year before ‘Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts,’ and everything you hear in the Beatles is there. And then you listen more. Especially to The Smile Sessions, and you hear all these other connections. Boom, there’s ELO, there’s another band.”

Both Cusack and Pohlad talked to Wilson but communicated heavily via Ledbetter, who handles many of his interactions. (Wilson was present at the premiere Sunday night and acknowledged the audience, to great cheers, when filmmakers nodded to him from the stage.)

For her part, Banks extolled Ledbetter’s gutsiness (she used a more salt-of-the-earth word) and said that she hadn’t even thought of the film as a musical biopic until it was brought up in an interview. “We’re ‘Get on Up’ but we’re totally different,” she said. “It’s really a story about villains, about good conquering evil.”

Thoughtful and soft-spoken, the Minnesota-based Pohlad, long known to movie writers for his involvement first as a high net-worth financier and then increasingly as a creative producer, directed one little-seen movie in 1990 but has mostly been financing and producing since. He has been involved with some of the more acclaimed movies of recent years, including “The Tree of Life” and “12 Years a Slave,” both of which he produced and helped finance. He said he didn’t set out to learn from the directors of movies like those but simply made the film that he thought seemed most original.

His own creative battle, he said, was to believe that he could make a movie in a familiar genre a little differently.

“I think every creative person, maybe every person, needs that element of ego or they wouldn’t do something like this. They need that kind of drive,” he said. “I think Brian has what a lot of us have. He just has it in really intense form.”

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.