TIFF 2014: With ‘Pigeon,’ director Roy Andersson goes out on a limb

Reporting from Toronto — Cult director Roy Andersson was sitting at his kitchen table in Stockholm, struggling to come up with an idea for a script, when he noticed a pigeon on his window sill.

“Immediately I thought. ‘Does he have problems too? Maybe he also is having trouble formulating a script,’” Andersson recalled. “It looks like easy living, but maybe it isn’t.”

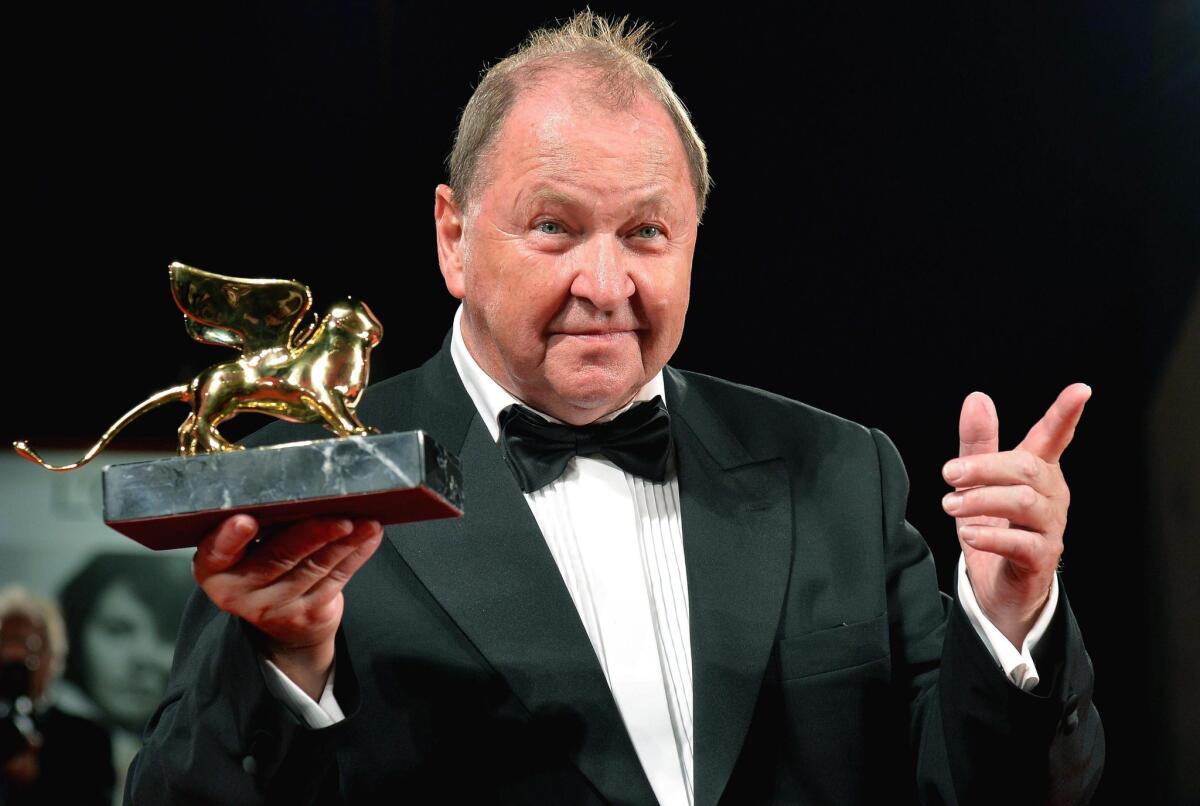

That whimsical musing captures the sensibility, though hardly the full breadth, of Andersson’s new film, titled after that sideways bit of inspiration. “A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Reflecting on Existence” is a blackly comic collection of 39 vignettes that examines the absurdity of ordinary life -- or just absurdity, period. When it won the top prize of the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival last weekend, it was a capper on a most unconventional career, to be sure, but also a valedictory to anyone who has ever seen the world through a similarly distorted lens.

About a dozen of the stories in the deadpan “Pigeon” follow the exploits of Sam and Jonathan, two hard-up novelty-item salesmen who are looking to pawn vampire fangs and other dime-store gags to anyone who’ll have them. They generally serve as the audience’s eyes into various tableauxs, if they’re not bickering or otherwise engaged in a kind of unintentional slapstick themselves.

In one short, a man keels over and dies in a crowded cafeteria, and the long pauses that follow involve the cashier and others wondering what to do with his paid-for lunch.

In the vignette that inspired the title, a young girl stands on stage in a school play and says she’d like to tell a story about a pigeon, who sat on a branch and realized he had no money, then decided to fly home.

And in companion shorts, Jonathan and Sam wander lost into an ordinary modern-day pub,when an entire cavalry of men in period dress on horses start riding by outside, historical reenactors (or perhaps time-travelers?). Several of them enter the bar, even flogging the patrons, and say they are serving a king, who they claim is the 19th century Charles XIV John of Sweden. Soon he shows up too. In the follow-up several shorts later, the same throwback army can be seen through the bar window returning down the street in tatters and humiliated defeat. If Steven Wright directed a remake of “Holy Motors,” it might look something like this.

“I think I’m an optimist,” Andersson said when asked about his animating philosophy, as he gives one of his trademark deep laughs, a gesture that suggests he’s enjoying himself and doesn’t want us to take him all that seriously. “Life is a tragedy. There’s no happy end for any of us. We all die. But there’s a lot of comedy in it. There’s comedy and vulnerability.”

Andersson is talking from a restaurant at a small boutique hotel at the Toronto International Film Festival. He has been staying here with his wife the last few days as his film screened to amused and wide-eyed audiences. The next day Andersson and his wife will return to Stockholm. It’s just after 3 p.m., but the director forgoes the festival staples of coffee or sparkling water and orders a Scotch. When you’re making comedic films about death, day drinking just sort of comes with the territory.

“Pigeon” is the culmination of a journey for Andersson, who turned 71 earlier this year.

In film school, Andersson was something of an enfant terrible. He and friends would take camera equipment and shoot protests of the Vietnam War. He was told to stop by a high-ranking administrator, who added that Andersson would never get work if he continued to make political documentaries. “I said, ‘Sorry, man, that’s bad advice,’” he recalled saying, and wrote a letter to the head of the Swedish Film Institute registering his objections. The high-ranking administrator was Ingmar Bergman.

Shortly after graduating, Andersson made two films, “Swedish Love Story” and “Giliap” -- the first a glossy commercial effort and the second an unmitigated commercial and financial disaster. In the mid-1970s, around the time the latter film flopped, he decided to make a change. Frustrated by what he saw as meddling and interventionism, Andersson took a Malickian hiatus, not directing a film for more than 20 years. He made commercials instead, using the proceeds to build his own studio.

“My goal was not to be in the hands of others,” he said. “I couldn’t listen to what all these other people had to say.” He continued working on numerous commercials (surprisingly given their aims, a lot of them had the same dark-comedy undertone), eventually amassing enough funds to finance movies himself for a career second chapter.

The beginning of that chapter came in 2000 with “Songs From the Second Floor,” when he was in his late 50s; he followed it in 2007 with “You, the Living.” Both are collections of shorts about what might be called the human dramedy. “Pigeon” is the third film in that loose trilogy, though it should be said these are thematic and formal, not narrative, sequels.

Andersson’s look at the downtrodden, wandering in search of hope or at least a gallows-humor laugh, was inspired by Italian neo-realism, movies such as 1948’s “Bicycle Thieves,” about a father searching for a bicycle to work, and others of that era.

He also looked at some less obvious inspiration in making “Pigeon.”

“It’s Oliver Hardy and Stan Laurel, or even Samuel Beckett. In Beckett, it’s three hours of nonsense but you just keep watching,” he said.

For all of “Pigeon’s” sharp comedy and apparent pessimism, there is a deeply kind spirit underneath it all. In one vignette, a man sits in a corner of a bar saying he’s been unhappy most of his life, and he thinks it’s because all his life he’s been ungenerous, a semi-explicit articulation of Andersson’s humanist worldview.

Visually, the scenes in “”Pigeon,” generally filmed by a static camera in a single take, are complex compositions -- there is often something happening in the corner of the frame, or on the audio track below the audio track.

A middle-aged man drops dead trying to open a wine bottle while his wife can be heard continuing to sing to herself as she washes the dishes in the other room. A pilot having a disappointing cellphone conversation outside a restaurant is flecked by the image over his shoulder of a second, wordless narrative playing out between an unlikely couple at a restaurant table.

“Pigeon” does not have U.S. distribution but is likely to land a deal and further festival play in the wake of the Venice win. Indeed, the recognition from a jury of cultural powerhouses -- this year’s group included composer Alexandre Desplat, actor Tim Roth and author Jhumpa Lahiri -- is no small deal.

Andersson heretofore has been known outside Scandinavia to a small group of critics and cultists only, an outsider even in a realm fashioned on outsiderishness. The idea that he would be crowned the leader of any group, even a rarefied one such as world cinema, comes as a surprise to anyone who’s followed his career. This, needless to say, includes Andersson himself.

“They told me I would be winning a prize. But I had no idea it would be that prize.” He said that he doesn’t mind being a “cult director” -- sometimes. “It’s a little flattering, but not always. The prize is enough but not enough. I am not ready for the sum-up of my career yet,” he laughed.

Andersson took a sip of Scotch and described his next project. “It will be the fourth in the trilogy. It will probably take about four years for my next film,” he said. “I want to do one that’s about eternity and then combine it with something called ‘Ali Baba and the Sixteen Thieves.’ Because, you know, it’s supposed to be 40 thieves,” He gave another good laugh. “But I think this will be more irritating.”

Twitter: @ZeitchikLAT

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.