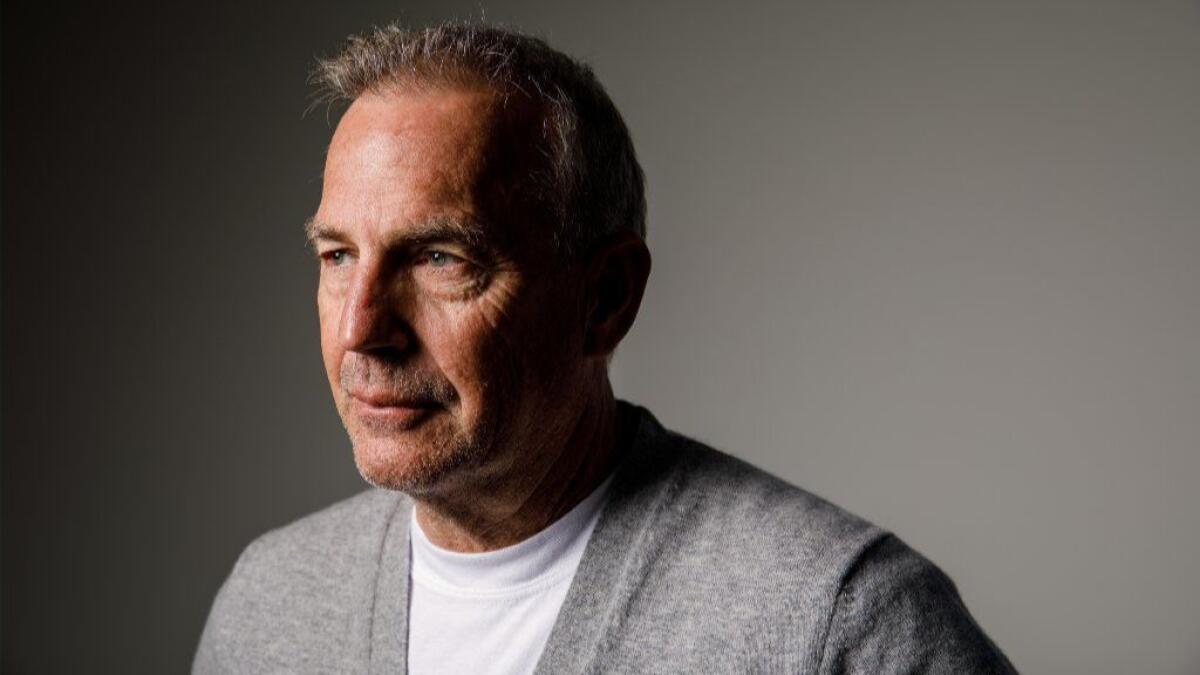

Kevin Costner wields power to protect his family’s dynasty in ‘Yellowstone’

Kevin Costner is in a tux. With a rifle.

A group of Chinese tourists has trespassed on the land of his “Yellowstone” character, John Dutton, to get a look at a large bear nearby. Dutton tries to persuade them to get back on their bus. They ignore him.

WATCH: 2019 Emmy Contenders video chats »

“Probably the scaredest guy out there is Dutton. If you notice in the scene, he’s doing this constantly,” Costner says, eyes darting all around as he talks in a conference room on the Paramount lot.

“They somehow don’t think [bears are] wild, and they are. Think of how confused John Dutton is. He’s on his way to a black-tie thing and, ‘What the ...?!’ ”

The notion of “Yellowstone,” the Paramount Network drama starring Costner as the patriarch of a Montana ranching clan, might evoke something like “Dynasty” with prettier scenery: Wealthy families holding on to their empire against other wealthy families. But the show was created, written and directed by Taylor Sheridan, whose scripts for “Sicario,” “Hell or High Water” and “Wind River” should reassure this won’t be clichéd. It returns for Season 2 next month, and Costner says they’re about to start filming Season 3.

Rather than “Dallas” or “Dynasty,” “Yellowstone” feels more like “The Godfather” on a ranch. The Dutton clan turns out to be nothing less than a crime family. There are “Godfather” echoes among the characters: a wayward, war-vet son on whom the father’s hopes are pinned (Luke Grimes), and a consigliere son (Wes Bentley). The daughter (Kelly Reilly), though, is more of a tiger than Talia Shire’s Connie ever was. And yes, Costner plays the Don Corleone figure.

Costner sees the parallels, but says. “Don Corleone didn’t have his fingers as much on the killing as I seem to. I’m a little closer to the thumbs up or thumbs down because I’m not dealing with a large organization; I’m dealing with my land.”

Dutton struggles to bridge the gap between his family’s Old West past and the rule-of-law present.

“It’s the times that are getting him. It’s the EPA, the Native American issues, the land-use permissions, urban development that’s encroaching on him that his father and his grandfather and great-grandfather, they didn’t have to deal with.

“Those people had nobody to arbitrate their problems but themselves. They didn’t have a PR person, an agent, a lawyer. Things were arbitrated in the West right at the moment.

“But you can’t touch anybody anymore; that’s assault. You can’t just redirect a river when you want to. And he’s got children who think it’s no longer the thing to be on the property. Previous generations felt lucky to be part of the Dutton dynasty. But these children have seen the world. They have TVs. They don’t have the same attachment.”

So John is a man a little out of time doing whatever it takes to protect his family’s interests — including ordering murders. Costner brings to him bootloads of gravitas, dressed in the solid, no-nonsense persona audiences are used to cheering on.

“The big note was he behaves like a king on his side of the wire,” he says. “He doesn’t think he’s a bad guy. Most bad guys don’t. He’s complicated.”

Despite the wide-open Montana vistas, there are figurative walls — and they’re closing in. The Duttons’ lawlessness is sure to have consequences.

“They’re coming. They have to come or we’re defying the law of gravity and modern civility. These things have happened. We have to deal with them. People are going to start coming to this Montana town, and noticing all the disappearances.”

Then he remembers the tourists and says, “I don’t want to have to kill that bear for those people, because I’m going to have to answer for that too.

“I think the randomness of [that scene] is ‘Yellowstone’ at its best. That’s when I enjoy it. The ranching goes on every day and there’s this intrigue that’s present.

“But to me, that’s a perfect scene, in a way. Look at him — he’s a rancher, he’s in a tuxedo, he’s about to go speak. He pulls a rifle and deals with a situation. ‘Every ... thing over there is mine and everything over here is mine. This is all mine.’ His anger is he’s afraid, more than anything. ‘My God, if I wouldn’t have been driving here, what might have happened?’ He might look back a little later and say, ‘Maybe I was a little harsh,’ but you can’t apologize for your survival instinct.”

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.