AT&T clinches $85-billion deal for Time Warner to create entertainment powerhouse

AT&T has reached a deal to buy Time Warner Inc. for $85.4 billion — a blockbuster marriage that would transform the telephone company into the nation’s largest entertainment company and a major force in Hollywood.

The agreement, which was hammered out at breakneck speed and announced by the two companies Saturday afternoon, accelerates the wave of consolidation sweeping through the telecommunications and media industries.

AT&T agreed to pay $107.50 a share to Time Warner investors in a cash and stock deal approved unanimously by both boards, the companies said.

“Premium content always wins,” said Randall Stephenson, AT&T chairman and chief executive. “It has been true on the big screen, the TV screen, and now it’s proving true on the mobile screen.”

By adding Time Warner’s expansive portfolio, which includes Hollywood’s largest film and television studio, Warner Bros., and such popular TV networks as HBO, CNN, Cartoon Network, TBS and TNT, the bulked-up AT&T would surpass Walt Disney Co. and Comcast Corp., which owns NBCUniversal.

“The whole industry is going to change,” predicted Jeffrey Cole, director of the Center for the Digital Future at the USC Annenberg School for Communication.

The trend of consolidation comes as technology advances have been upending traditional entertainment companies. Many in the industry believe that getting bigger is the best way to compete with companies like Google, Apple, Netflix and Facebook.

Time Warner Chief Executive Jeffrey Bewkes said Saturday that AT&T -- with more than 100 million cell phone customers -- provided a potent platform to deliver Time Warner’s programming to consumers.

“We think AT&T has tremendous capabilities that we don’t have on our own,” Bewkes said. “This is a unique combination.”

The companies have a shared culture of innovation, he said, citing AT&T and Alexander Graham Bell’s invention of the telephone and Warner Bros. creation of the first feature films with sound. An AT&T-Time Warner union would create a new leader in 21st Century entertainment, he said.

Even before the merger was announced, critics were blasting the colossal combination. The deal must win the blessing of federal regulators, including the U.S. Department of Justice, posing an early test for the winner of the presidential election. Republican nominee Donald Trump said in a speech in Gettysburg, Pa., on Saturday that he would ”look at breaking this deal up” because it would give AT&T “too much concentration of power.”

Mark Lemley, a professor at Stanford Law School and director of the Stanford Program in Law, Science and Technology, said Saturday that the merger raises “very significant” antitrust concerns.

“I would be surprised if the antitrust authorities let this one pass,” Lemley said. “There has been a wave of big mergers by direct competitors, and the government has been increasingly aggressive in challenging those mergers.”

The proposed takeover represents AT&T’s second substantial foray into entertainment. Last year, the company spent $49 billion to buy DirecTV, based in El Segundo, and immediately became the nation’s largest pay-TV provider with more than 25 million customers.

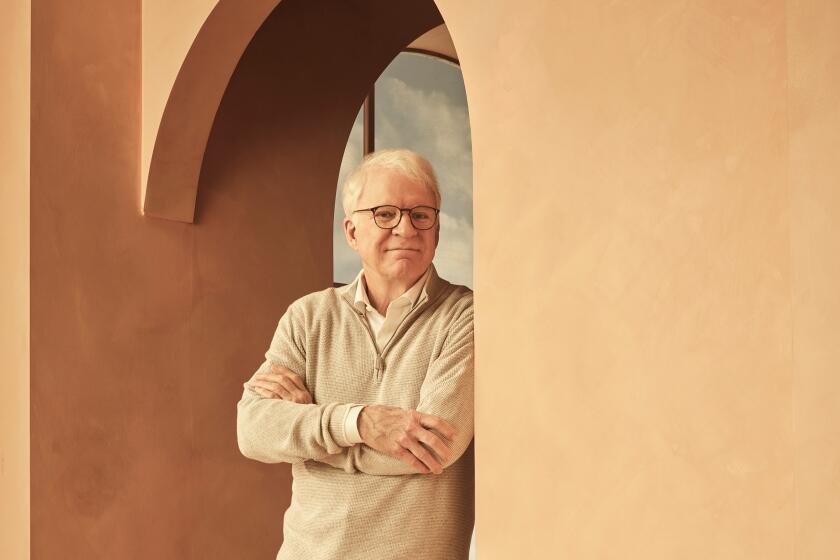

Stephenson, 56, is making a bold bet that his company will be better equipped to ride out the challenges roiling the industry if it owns premium entertainment properties and more programming that can be delivered to mobile phones, which have become an indispensable part of the daily lives of consumers.

DirecTV has a handful of TV channels but nothing on the order of Time Warner’s popular cable TV networks. The deal would hand AT&T the keys to Warner Bros., which produces such beloved TV shows as “The Big Bang Theory,” and churns out blockbuster movies, including the Harry Potter and DC Comics franchises.

Time Warner, meanwhile, has faced its own challenges trying to coax younger viewers to watch its channels at a time when millennial audiences are ditching bigger screens for their smart phones.

Still, there’s no guarantee the merger will deliver the hoped-for synergies, and company leaders will have to meld dramatically different corporate cultures.

“I’m wondering if AT&T would have the temperament to run an entertainment company,” USC’s Cole said. “I’m not sure a phone company would have the willingness to tolerate the ups and downs of the entertainment business.”

Time Warner spent years trying to recover from the disastrous 2000 merger with AOL, widely viewed as the worst merger ever. During the past decade, Bewkes has been steadily peeling off properties — AOL, the Time Warner Cable TV distribution service and even its vaunted Time magazine unit — which made Time Warner a more attractive acquisition target.

Two years ago, Time Warner fended off the hostile takeover bid of Rupert Murdoch and his media company. Murdoch’s 21st Century Fox offered $85 a share for Time Warner, a deal valued at about $80 billion, but Bewkes insisted that Time Warner would fare better on its own.

The deal that Bewkes struck with AT&T was 25% higher in value than the Murdoch deal and represented a 35% premium compared with the share price earlier in the week.

Even as legacy media look to solidify their positions, approval of the merger is not guaranteed. Politics may play a substantial role in the review, experts said.

“The potential for government antitrust policy to move left under a Clinton administration is a risk,” said Paul Gallant, with Cowen Washington Policy Group, in a research note. “Still, we think approval of a deal ... is more likely than not.”

Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton said on her website that she plans to protect consumers by strengthening antitrust laws and enforcement in order to “promote competition” and “address excessive concentration” of power among corporations. She has not weighed in on the merger.

George W. Bush took a hands-off approach to mergers with cable and media companies. But the Obama administration has become increasingly aggressive at reviewing proposed mergers and blocking deals they view as anti-competitive.

Last year, Comcast abandoned its proposed takeover of pay-TV distributor Time Warner Cable (a separate company from Time Warner) after federal regulators indicated they would try to block the deal.

Amid similar concerns, AT&T withdrew its proposed $39-billion takeover of competitor T-Mobile in 2011, paying about $4 billion as a breakup fee.

In some cases, regulators approve mergers with heavy restrictions, such as when Comcast acquired NBC Universal in 2011. NBC Universal agreed to give up management rights of streaming service Hulu for several years, and Comcast agreed not to discriminate against competing online video distributors or rival cable channels.

Stephenson said he expects the deal to win regulatory approval, perhaps with some conditions. “That’s what we anticipate happening here,” Stephenson said in a conference call with reporters Saturday evening. “No competitor is being removed from the marketplace, there is no competitive harm that is being rendered by putting these two companies together.”

Critics aren’t convinced and believe that consumers would ultimately lose.

“It’s a massive concentration of industry power — and a massive amount of political power,” Matt Wood, policy director for the advocacy group Free Press, said. “Big mergers like this inevitably mean higher prices for real people, to pay down the money borrowed to finance these deals and their golden parachutes.”

Times staff writers Noah Bierman and Ryan Faughnder contributed to this report.

UPDATES:

6:52 p.m.: This article was updated with details from an AT&T and Time Warner conference call with reporters.

5:23 p.m.: This article was updated with analysis and reaction to the deal.

4:50 p.m.: This article was updated with official news of the deal.

4:25 p.m.: This article was updated with additional details and analysis.

This article was originally published at 4:05 p.m.

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.