James Earl Jones, Cicely Tyson back on Broadway in ‘Gin Game’

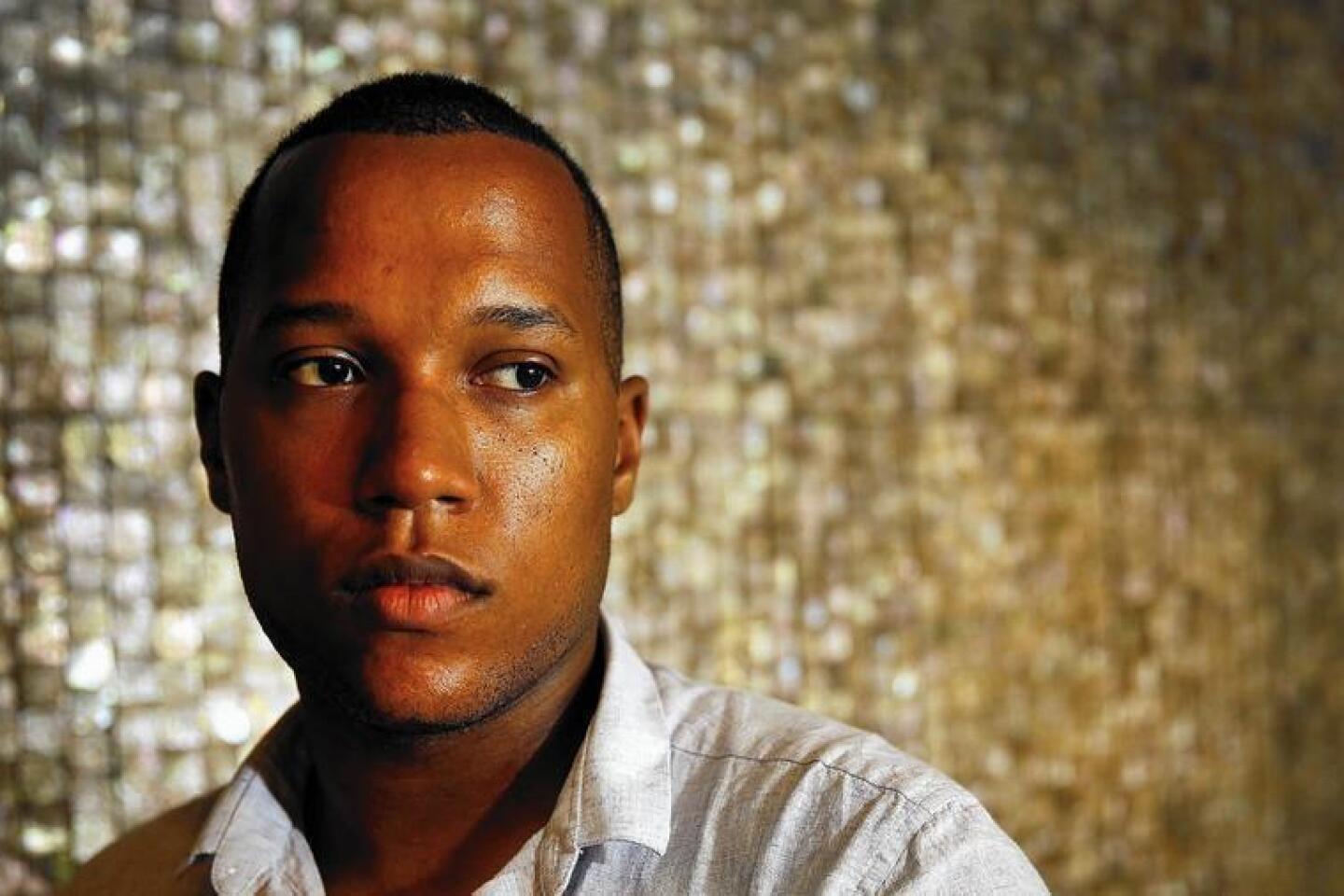

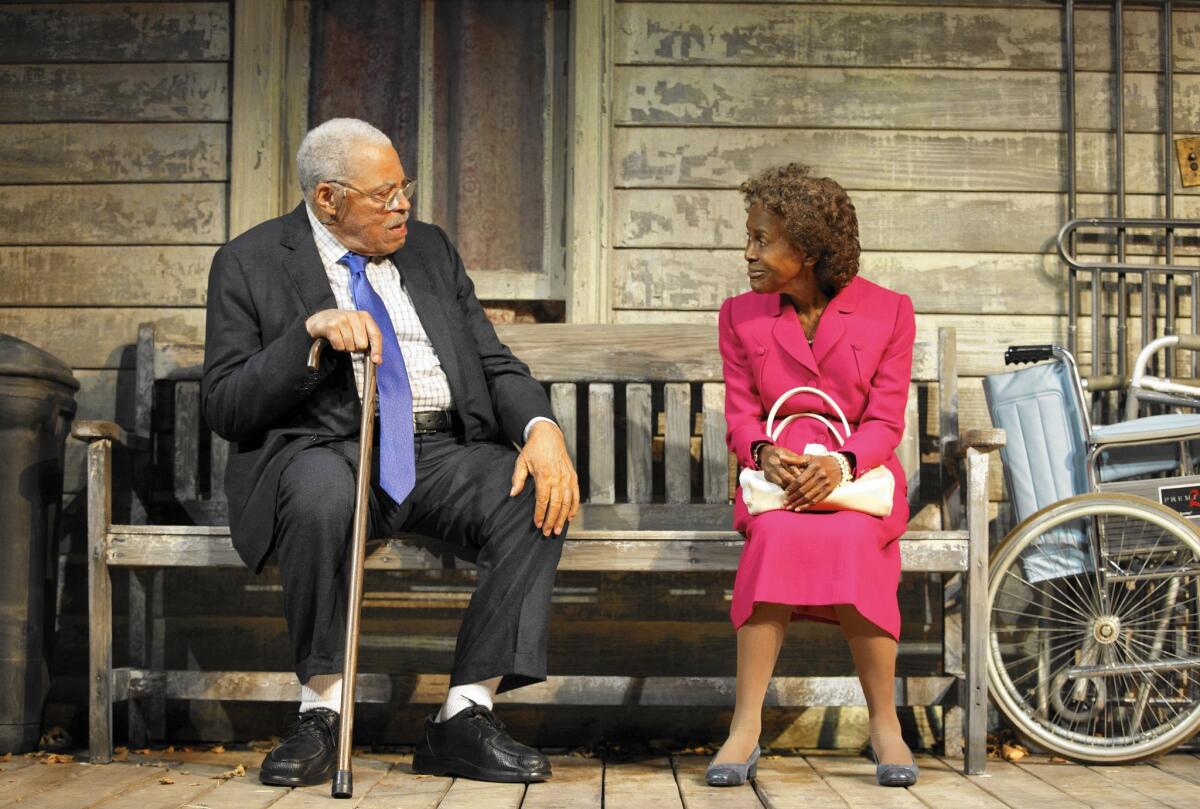

reporting from NEW YORK — At the top of several steep flights of stairs behind the stage at Broadway’s Golden Theatre, an unmistakable baritone voice boomed out of a dressing room door. “Are you feeling those stairs?” James Earl Jones asked. It was clear that the 84-year-old actor, who was snacking on grapes, was not, in fact, feeling the stairs. Nor was his costar in the dressing room one flight below, 90-year-old Cicely Tyson, who had arrived in leather pants, silver Ugg boots and a baseball cap, bounding into an interview with a bunny-like energy.

Jones and Tyson are in a revival of “The Gin Game,” a two-person play originated on Broadway in 1977 by Hume Cronyn and Jessica Tandy. The new production, which opens Wednesday and runs through Jan. 10, reunites the two trailblazing African American actors who first shared a stage in a 1960s production of Jean Genet’s “The Blacks.” This time they star in a rare piece of theater that places the fears and hopes of older people at center stage.

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter >>

In the play, written by D.L. Coburn and directed by Leonard Foglia, the characters flirt, scuffle and try to stave off the loneliness of life in a low-rent retirement home by playing gin. Jones is Weller Martin, an ornery egotist who declares that he is suffering from “one of the worst cases of old age in the history of science,” and Tyson is Fonsia Dorsey, a teary newcomer whose people never come on visiting day.

A hilarious physical mismatch — Jones is 6-foot-2 and broad-shouldered, Tyson 5-foot-3 and thin — they are nevertheless equal players in both stage presence and historical significance.

The two stars have led parallel careers with groundbreaking roles. After “The Blacks,” Jones made his mark in the fictionalized portrayal of boxing champion Jack Johnson, “The Great White Hope,” which opened on Broadway in 1968 and was adapted to film in 1970, while Tyson earned an Academy Award nomination as the wife of a Depression-era sharecropper in the 1972 movie “Sounder” and played a woman living through slavery and segregation in the 1974 TV movie “The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman.”

“She and I emerged in the same period and flowered in a way and went into an orbit,” Jones said. “The Blacks,” he added, “was about revolution. And that was our beginning. ... It was a phenomenon and coincided with Martin Luther King’s civil rights movement. Our production shared energy off that whole consciousness that was being awakened in America.”

“He’s so big and boisterous, with all the thunder of a lion... Because I was consistently facing the audience, I acquired a way to laugh and not move a muscle in my face.

— Cicely Tyson on James Earl Jones

Asked, in separate interviews, to recall their first impressions of each other in “The Blacks,” in which they played a couple, Jones described Tyson’s beauty (“She was what the boys now would call ‘hot,’ ” he said), and Tyson said that Jones had made her laugh uncontrollably.

“He’s so big and boisterous, with all the thunder of a lion,” Tyson said. “Because I was consistently facing the audience, I acquired a way to laugh and not move a muscle in my face.”

Their wildly different temperaments come across in brief interviews: Jones, reserved, reads some lines of poetry that informed his character, while Tyson walks into the room and hands over a piece of chocolate, saying, “It’s good for you.”

“These are two people who love to work,” director Foglia said. “That’s all they want to be doing. James Earl walked in on the first day of rehearsal knowing every word. That’s always his process. He doesn’t like to walk around with a script in his hand. Cicely is the opposite. She’s more improvisational. She works in any way she can to find her way into the moment.”

Jones, who is self-critical, enlisted the help of expert card handlers for his card shuffling scenes; Tyson, who has been playing grandmother roles for 40 years, said she opted not to force anything in rehearsal discussions about her character’s walk.

“I’ve played so many old women, where am I gonna get another walk from?” Tyson said. “After I got Fonsia’s shoes, I found myself walking in a funny way, kind of rocking side to side, and I thought, ‘Oh, that must be her. She just took over my body.’ ”

Tyson plays Viola Davis’ mother in the ABC show “How to Get Away With Murder.” Asked about the speech Davis delivered at the Emmy Awards in which she cited the lack of opportunities for black actresses, Tyson reflected on the long dry spells she endured between acting jobs over the decades.

“I couldn’t be black and not have it impact my career,” Tyson said. “I went for years not working. I guess every two years maybe I’d get a role. Intermittently I’d find something to do. I just would not allow myself not to work.”

When she couldn’t find acting work in the 1970s, Tyson said she turned to public speaking, traveling to Europe and Africa to deliver motivational speeches.

Jones, who is nearly as famous for voicing Darth Vader in “Star Wars” films and Mufasa in “The Lion King,” has starred in many plays that were not originally written for black actors, works from Shakespeare to Tennessee Williams.

“I was born on a farm in Mississippi,” Jones said. “I knew what the social faults of this country have always been. A lot of them are still there. I’ve not paid much attention to it. I’d rather pursue the work than pursue an activist approach to the work. ... I hear people reporting about problems with Hollywood, for instance, with papers that say don’t even bother trying to tell stories about black people or women, because they won’t find an audience. That was an old-time dictum, really, they’re proving wrong.”

Both Jones and Tyson said they came to acting not for fame or wealth but for expression. Jones, once a stutterer, was lured by language, and Tyson, who was introverted, by a vehicle to communicate.

“I was extremely shy as a child,” said Tyson, who was born in Harlem, the child of immigrants from Nevis, in the West Indies. “When I found I could speak through somebody else, that I could express my emotions, that’s what hooked me. Once I was allowed the expression, the release of my emotions, then I felt like I was a person.”

With six performances a week in a play in which they are the only two characters — a task that might be daunting to actors decades younger — Tyson and Jones said they are energized by their work.

“When I leave every night, I feel good the way an athlete feels good after a good workout,” Jones said. “Maybe it’s the other kinds of energy I’m allowed to release in the play. It’s not about the performance. But the energy.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.