An exhibition on L.A.’s queer Chicano networks shows how California artists connected with the world

Macario “Tosh” Carrillo is not a name you often hear associated with Chicano art. An actor, props designer and photographer, he appeared in New York avant-garde theater during the mid-1960s and starred in several Andy Warhol experimental movies, including “Camp,” “Vinyl” and “Horse.” In the latter, a homoerotic play on old westerns that brought a live stallion into Warhol’s East 47th Street studio, Carrillo appeared as a character named “Mex.”

Throughout his career, Carrillo was identified as Puerto Rican. But he was actually Mexican American: born in Texas and likely raised in the Los Angeles area, with family scattered around California. By the ’70s he had relocated to San Francisco where he launched a design firm.

He died in 1983, during the earliest days of the AIDS crisis. But his work and his story have resurfaced in “Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A.,” a two-part exhibition, part of Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA, on view through the end of the month. Part of the works can be seen at the Museum of Contemporary Art’s Pacific Design Center outpost; the rest are at ONE Gallery, the West Hollywood exhibition space of the ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives.

Carrillo’s biography is patchy. But an extensive archive of his negatives survive — and images from that archive are now on display as part of “Axis Mundo.” This includes a series of black-and-white photographs that capture his creative and social milieu: matter-of-fact images featuring androgynous young bohemians, a mustachioed man posing with eyeliner and turban, a playful young woman covered in feathers.

“It’s a peek into broad queer circles, but in a different form from the better-known photographers of the era,” says exhibition co-curator C. Ondine Chavoya, who stumbled into Carrillo’s negatives in a New York Public Library archive in 2008. “There is a vulnerability to the images.”

“It’s not clear if some of them were commissioned,” he adds. “But it does seem that these are people he is meeting and traveling with — perhaps an erotic encounter or two.”

Carrillo’s presence in a show centered on the queer Chicano experience in Los Angeles may seem unusual since the artist spent much of his career in New York. But it speaks to the complex and layered nature of “Axis Mundo,” which doesn’t attempt to define the canon of what is “queer” and “Chicano” and “Los Angeles.” It instead seeks to examine the expansive networks artists established for themselves from the 1960s to the ’90s — a time when the queer and the Chicano received little airtime in mainstream cultural circles.

The show reveals the contacts and influences that nurtured young painters, writers and filmmakers — a web that extended from Chicano cultural hot spots such as East Los Angeles to Andy Warhol’s Factory in New York, political art circles in Uruguay and the gender-bending performances scene in 1970s London.

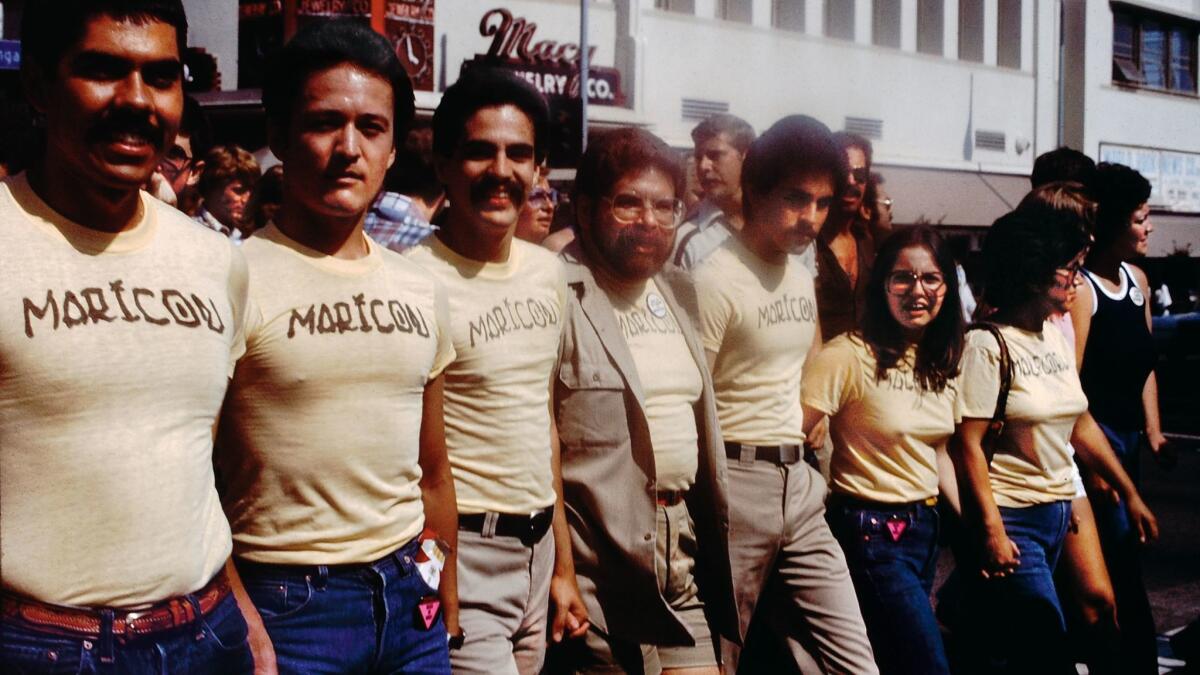

Certainly, the show addresses the defining facets of the queer Chicano experience: of desire, of activism, of intimacy, of the ravages of AIDS and of being caught in between a dominant white society and a Latin American culture that prizes machismo and servile femininity.

It does this through a wide gamut of media, including photography, painting, poetry and video — not to mention a display of the flamboyant outfits worn by the artists of Les Petites Bonbons, a glam conceptual group that didn’t play music, but nonetheless dressed and behaved like rock stars.

“It’s performance, it’s conceptual art, it’s everything,” says co-curator David Evans Frantz, who is also curator of the ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives at the USC Libraries. “There is a vibrancy to the forms of experimentation. It’s all churning. It’s punk, it’s photography, it’s everything.”

The show also features artists whose identities extend beyond queer Chicano circles — including figures such as British body artist Genesis Breyer P-Orridge, singer-songwriter Phranc and Milwaukee-born conceptualist Jerry Dreva, a founder of Les Petites Bonbons and a frequent collaborator of painter and conceptualist Gronk (born Glugio Nicandro), an artist who, among other things, was a founding member of Asco, the influential East L.A. art collective.

The curators’ decision to include these artists was inspired by a number of groundbreaking exhibitions held in Los Angeles in the mid-’70s that focused on Chicano identity.

“We looked at exhibitions organized loosely under the rubric of Chicano art,” Chavoya says. “One of them was a show called ‘Escandalosas!’ which the artist Richard Nieblas held in his house [in East L.A.], which he temporarily renamed the ‘Hazard Gallery.’ It was organized loosely as a Chicano gay exhibition — maybe the first one of its time. But if you look at the roster, there are non-Chicano artists in the show and non-queer artists in the show.”

In addition to this cultural mix, “Axis Mundo” also puts multi-generational connections on display.

The work of photographer Judy Miranda, whose practice included abstracted portraiture and street photography, appears throughout the exhibition. Miranda moved to Denver in the late ’80s, and her work hasn’t been seen much in L.A. over the last 30 years, but she nonetheless had an indelible influence.

“She was one of the only Chicana photo teachers in Los Angeles in the 1970s,” says Chavoya.

One of her students at East Los Angeles College? A queer Chicana named Laura Aguilar, whose work has explored myriad facets of Latina lesbian identity as well as the organic forms of her own body. (In addition to being represented in “Axis Mundo,” Aguilar is also the subject of a one-woman show at the Vincent Price Art Museum.)

Even as “Axis Mundo” charts overlapping communities of artists, it does contain some important centers of gravity.

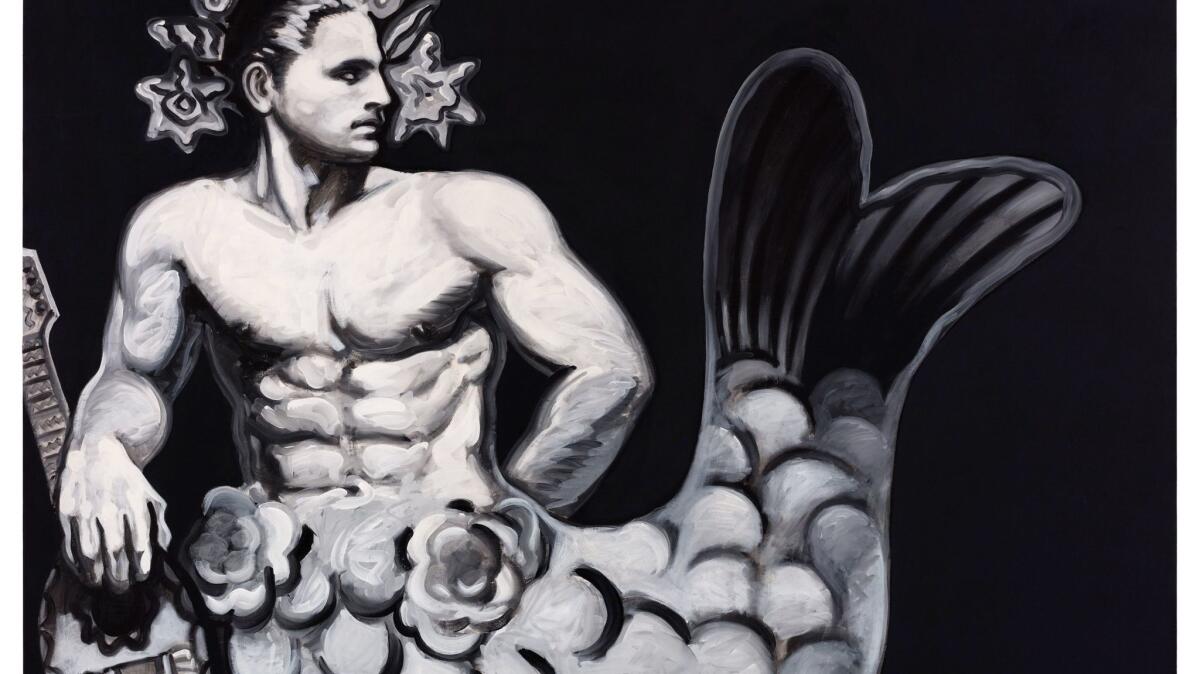

The first is the work of the late Edmundo “Mundo” Meza, a Tijuana-born artist who grew up in Los Angeles and later became known for creating paintings that toyed with gender and depicted the male figure in often sensuous ways. (This includes the striking “Merman With Mandolin,” which sits at the center of MOCA’s piece of the “Axis Mundo” display).

But Meza was much more than a painter. He also collaborated with figures such as Gronk and the performance artist Robert Legorreta, who was known for his wild and gritty performances as a character of indeterminate gender, Cyclona.

Frantz says Meza’s name came up repeatedly when he and Chavoya began researching L.A.’s queer Chicano art scene. This is why the exhibition title nods to Meza’s nickname, Mundo, which also means “world.” His works are hung throughout both shows.

“He was spoken with great reverence by his collaborators,” Frantz says. “There is this aura to how he was described. And that started a discovery process. We start with him as the fulcrum and then we look at his peers and then it grows and grows and we discover these robust, rich multiple connections.”

In the ’80s, Meza collaborated with British creative director Simon Doonan (also his lover at the time) on window displays for Maxfield and other Melrose Avenue boutiques — before Doonan became creative ambassador for Barneys New York. These outré installations came to feature Meza’s large-scale paintings and funny-surreal mannequin configurations, including smiling dummies with their pants around their ankles and a taxidermy coyote dragging away a child. (Doonan has described these as reaching “new heights of provocation.”)

Like a lot of artists in the show — whose work has been drawn from garages and storage units and obscure institutional archives — Meza’s art hadn’t been seen in a significant way since he died of AIDS-related complications in 1985. His work has made appearances in group exhibitions over time. But he hasn’t been the subject of serious consideration since Doonan and artist Jef Huereque (who was Meza’s partner before he died) organized a retrospective of his work at Otis College of Art and Design in the wake of his death.

Frantz says Meza’s work is significant not just for its dexterousness, but for what it reveals about how queer Chicano artists worked during that era.

“It’s a broad tenacity that was about creating and producing and showing. It’s about artists doing it themselves.”

In that regard, “Axis Mundo” could be said to have another gravitational center: its DIY spirit. Art was made by hand. Shows were staged in homes, warehouses and shop windows. Everything and anything was art.

There are Cyclona’s outrageous ensembles crafted from thrift store materials. There are hand-made collages by the likes of painter Carlos Almaraz and punk rocker Gerardo Velasquez. And cheap zines with titles such as “Masturbirthday,” “Egozine” and “Homeboy Beautiful” — the latter a satirical magazine by Joey Terrill that skewered machismo and homophobia.

The show includes countless pieces of mail art — small works designed specifically to be distributed through the postal service — including Dreva’s palm-sized razor blade crucifixes and Asco’s staged tableaux of co-founder Patssi Valdez in sci-fi ensembles.

This allowed the work of these artists to travel far and wide. Drawings by L.A. painter Teddy Sandoval reached political artists who had been imprisoned in Uruguay and ended up in the hands of the Canadian collective General Idea, whose archive is now housed at the National Gallery of Canada.

“Mail art provided a very accessible format for circulating their work and circulating it widely,” Chavoya says, “and getting it out to a national and international audience.”

The materials at times may have been crude. But the message was not — and it traveled far. Artists, imbued by the tools and language of ’70s activism (Chicano, gay and feminist) presented a new possibility for what could be considered mainstream.

“In the face of institutional neglect, they created their own forms,” Chavoya says.

“The way in which these artists rose to the occasion to combat perceptions and raise political discourse, those are inspiring stories,” adds Frantz. “In fact, those are the things we need in this moment.”

“Axis Mundo” may look at the past. But it is very much about the present.

“Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A.”

Where: Museum of Contemporary Art Pacific Design Center, 8687 Melrose Ave., West Hollywood and ONE Gallery, 626 N. Robertson Blvd., West Hollywood

When: Through Dec. 31

Info: moca.org, one.usc.edu and pacificstandardtime.org

Sign up for our weekly Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

ALSO

'Radical Women' at the Hammer Museum is a startling show you need to see, maybe twice

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.