Q&A: Hugo Crosthwaite on Tijuana, Mexico’s missing, the power of comic books

Walk into the rear gallery at Luis De Jesus in Culver City and it will appear as if a wall has exploded. Scattered about the floor are jagged pieces of images that together seem as if they would form a mural — and indeed, that is the idea. The fragments are part of a work by Mexican artist Hugo Crosthwaite titled “Shattered Mural.”

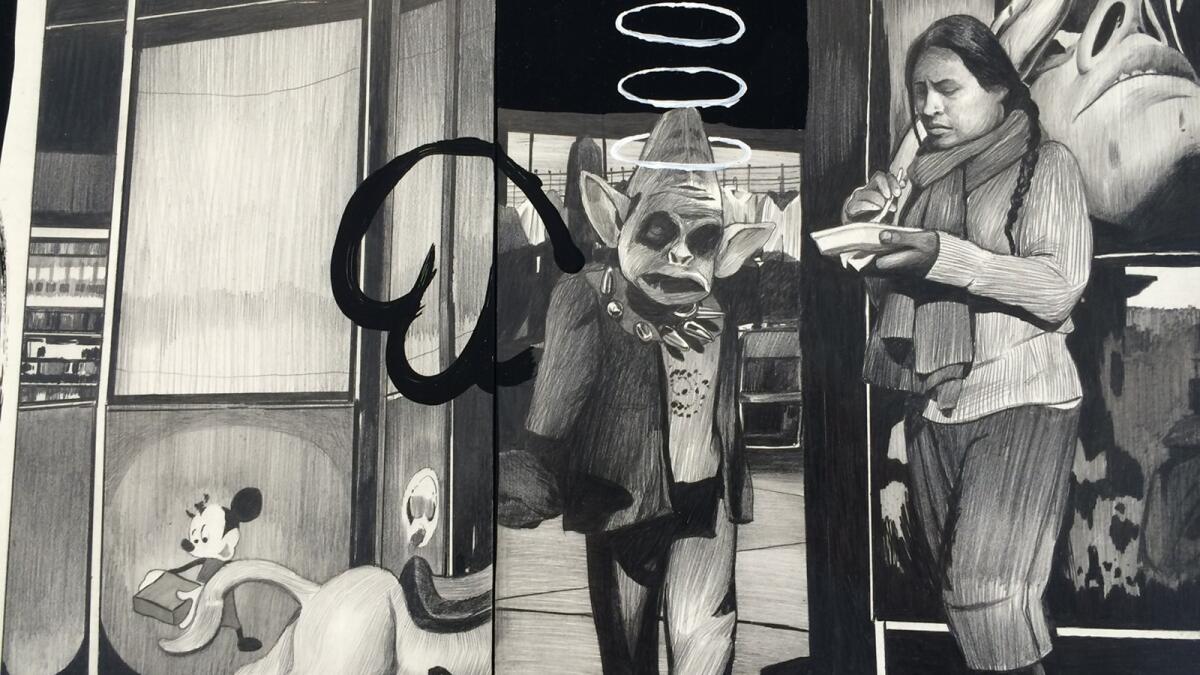

On first glance, the piece looks like a family photo that’s been torn to bits. Painted onto the individual pieces are Crosthwaite’s signature black-and-white images of people, rendered in a style that draws as much from 19th century French illustration as it does from the wild comic book lines of Jack Kirby. Here and there, you see children, young women, grinning men and the outlines of garish cartoons.

The piece, in many ways, addresses the countless lives claimed by Mexico’s ongoing drug war — a response to the disappearance of 43 students from Ayotzinapa in the fall of last year at the hands of police. It is on display in a two-part show at Luis De Jesus that also features a series of Crosthwaite’s wall works, pieces inspired by the people and landscape of his native Tijuana.

The fragments of Crosthwaite’s “Shattered Mural” contain images of people real and imagined. Many of the real-life figures are drawn from his wanderings around Tijuana.

The artist took some time to chat with me via Skype from Rosarito, just south of Tijuana, where he is currently based. (He also spends long stints in New York.) Crosthwaite discusses what led him to make “Shattered Mural,” what inspires him about Tijuana, and why comic book art has proved so instructive.

You made “Shattered Mural” in honor of the 43 students from Aytozinapa who went missing late last year. What inspired this piece? And why have a tribute to them as a mural rendered in fragments?

I had been working on this show for two years and I started with the work that you see in the first gallery [at Luis De Jesus]. That work looks almost like crossword puzzles. They almost look like they want to come together and form something, but they really don’t. If you do put them together, they don’t form a unified narrative. When I got the second gallery, I thought, I’ll do the opposite: I’ll create a puzzle of all these pieces that do come together.

And that was right around the time Ayotzinapa happened. I remember, some stupid politician said something like, “Why are we making such a big fuss over 43 students?” I was infuriated. It’s not just 43 students. It’s thousands. It’s tens of thousands of people that have been killed.

So I thought, I’ll do a mural where I show people — figures from Tijuana and Rosarito and historical figures, with elements of [José Guadalupe] Posada and other icons — and then I’ll shatter that mass of people. I wanted the idea of the humanity of Mexico being shattered.

Is this one mural shattered into 43 pieces? Or is it 43 individual murals? So you start to deal with this exponential number. That gets back to what the politician said. It’s not just 43. It’s an exponential 43.

A view of Crosthwaite’s ‘Shattered Mural’ installation from behind reveals fragments of wallpaper patterns — as if literal pieces of wall had been cut up and scattered about the room.

The back sides of each of these pieces is covered in these quite lovely and very inoffensive decorative patterns. How did that idea come about?

I remember once in Tijuana and I did a mural and someone came and said, “I really like this dog. Can I cut the piece of the wall with the dog?” And I said, “I’ll do another dog.” And he said, “No I want that dog.” So we looked into cutting the wall. On the other side was a boutique, with this very nice wallpaper. I didn’t get to cut it. But that stayed with me. I like the idea of my drawing with this very nice wallpaper in the back. So for this piece, I created these Xerox transfers of very common wallpaper patterns.

In the fragments, you see images of performers, idols, cartoonish figures and what appear to be drawings of real people. Who are the individuals you feature in this piece?

It’s the idea of capturing all of humanity and their idiosyncrasies. You get La Llorona [the weeping woman of Latin American legend]. You get El Santo, the famous luchador. You have these dead babies that are dressed up as saints — part of this notion of sanctity from Catholicism. I did this image like of [the legendary actress] Maria Felix, a romantic figure, but she’s next to this monster. And there are the people I capture from my own sketches around Tijuana. They are not people I know. I just go to the market or I walk the street and I take pictures of people coming and going, very regular people.

I did not want to feature the missing students. I wanted to be respectful. I wanted the idea of Mexico shattered over the massacre of these 43 students. But I didn’t want to do a literal memorial in a gallery where the work will be sold. That is not appropriate.

I wanted the idea of the humanity of Mexico being shattered.

— Hugo Crosthwaite

In your work, you’ll often pair some really mundane activity (a guy making tacos) with something outrageous (a half-dressed woman right over his head) — as if you are revealing what can’t always be seen.

Well, I was playing with this notion of a puzzle — a puzzle you couldn’t unite. But I started seeing small things, aesthetic things, that could be connected: There might be a line in one drawing and you’d see it in another drawing. I then started thinking of the whole notion of these very disparate narratives and how they unite in some way, but they’re not literally connected. In a way, they are forced to be connected.

Well, that’s what happens in a city. You can’t choose your neighbors. So you will have the taco stand and then above it, you’ll have the brothel. There is a connection and it’s Tijuana, it’s the grittiness of the city, this city that is improvised and chaotic.

Crosthwaite is also showing a series of his wall pieces: puzzle-like assemblages of images that feature layers of drawings and paintings. Often, the artist will add fantastical elements to drawings of real people he sees on the streets.

On view, you have another series of works called “Tijuana Radiant Shine.” These feature strange views of the city: a man with a monstrous mask, a dummy sitting in a car, weird apparitions. How much of this is the actual Tijuana landscape and how much of this is your own invention?

They’re a mixture of everything. They’re a mixture of sketches that I do. I’m always making ink drawings. There are faces that I see and I draw them. Then the rest, I make up from other imagery: from comic books, from newspaper articles. I take a face and then I unite them with other things. I might need an arm, so I might grab it from a comic book. Or if I’m looking from a leg, I might get one from a fashion magazine. Many of [my figures] are like Frankenstein monsters made up of all these different parts. You can do that in drawings. You can take all of these elements and you mold them together into one piece.

The drawing that shows the dummy sitting in traffic: That’s cars in line at the border. I didn’t want to draw a person, so I grabbed a face from a fashion model and the body, I took it from a 1930s pictures of a clothing dummy. But then I worked on it to make it into a whole composition: this dummy sitting in traffic.

It’s about how you feel when you’re trying to cross the border. It should take you five minutes, but you can be there for hours.

A detail from the “Tijuana Radiant Shine” series, which brings together real and imagined pieces of the artist’s native city.

Comic-book style characters regularly appear in your work. How much of an influence have comic books been for you?

I didn’t read comic books as a kid. I came to comics when I was in New York. I was incorporating a lot of the graffiti I saw in New York into my work. I started to get into this graphic kind of work and that led me to comic books and Jack Kirby and black-and-white comic books — a little bit of everything.

I often do wall installations and they will give me four, five days to complete it. It’s not like the work I usually do which is very dense. I’ve done murals that took me nine months. But often I don’t get that kind of time. So I’ve been looking at comic books for their simplicity of line and the ways in which they tell a narrative simply. Comic books do that. It’s very effective.

How does Tijuana inspire you as an artist? What aspects of the city are we seeing of it in your work?

I think my first motivation is the aesthetics of the city. I call it a chaotic sediment of urbanization. It also comes from my growing up in the curio shop that my father ran. Everything was a mess, but it was an organized mess. There was an order to it. But at first impression you come in, it looks like a mess.

You go to a store in the U.S. and everything is really neat and perfect. But you go to a shop in Tijuana, every little corner is filled. It’s almost baroque. And it looks like there is no plan. That’s what Tijuana is. At first impression, it looks chaotic. But it has an order to it.

Hugo Crosthwaite’s “Tijuana Radiant Shine” and “Shattered Mural” are on view at Luis De Jesus Los Angeles through June 20. 2685 S. La Cienega Blvd., Culver City, luisdejesus.com.

Find me on Twitter @cmonstah.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.