As Trump talks building a wall, a Japanese art collective’s Tijuana treehouse peeks across the border

Reporting from Tijuana — As treehouses go, this one offers unparalleled views. To the north are the scrub-covered slopes of the San Diego National Wildlife Refuge. To the south are the ramshackle constructions of Tijuana’s Colonia Libertad neighborhood, with its tire retaining walls and patchwork roofs of corrugated tin. Stretching into the horizon to the west is roughly seven miles of undulating steel border wall separating Mexico from the United States.

The U.S.-Mexico border is no ordinary place. And this is no ordinary treehouse. It is a work of art built by a collective of Japanese artists known as Chim Pom. The backyard treehouse, on the Tijuana side of the border, also functions as a wry viewpoint over one of the most politicized borders in the world.

For the record:

1:20 p.m. Jan. 25, 2017This article states that the artist Ellie flew to Hawaii in 2012 for a shoot with a Japanese video crew who were subsequently banned from entering the U.S. The artist was preparing to fly to Hawaii when the incident occurred.

“It’s our art,” said Ryuta Ushiro, a member of the collective, “but it’s also for children.”

The installation couldn’t be more timely. Newly inaugurated President Donald Trump has made building a wall on the U.S.-Mexico border a high priority — mentioning it Jan. 11 during his first official news conference in months, when he told reporters, “I want to get the wall started.”

But the wall remains controversial. Only 37% of Americans support building it, according to an ABC News/Washington Post poll released last week. And on Monday, ABC ran an interview with the outgoing head of the Customs and Border Protection agency, who cast doubt on the project’s utility.

“I think that anyone who’s been familiar with the Southwest border and the terrain … kind of recognizes that building a wall along the entire Southwest border is probably not going to work,” stated Gil Kerlikowske, commissioner of the CBP under President Barack Obama. “When we look at the cost — and we have about 600 miles of fencing now — we look at the maintenance and the upkeep, we know how incredibly difficult it is.”

This puts Chim Pom’s sardonic treehouse, located in a private backyard about 2 ½ miles east of downtown Tijuana, at the center of a charged political storm.

Earlier this month, just as Trump was making his comments about getting construction on the wall started, I met with Ushiro and fellow Chim Pom member Motomu Inaoka in a drizzly supermarket parking lot on Tijuana’s traffic-jammed Boulevard Cuauhtemoc. From there, the pair drove me into the hills of Colonia Libertad, a neighborhood that is framed by the infrastructure of transit — and the denial of transit: A railroad to the west, the Tijuana International Airport to the east and the U.S.-Mexico border wall, just to the north.

Ushiro, a slim young man in a pork pie hat, said that Chim Pom grew interested in the border for a variety of reasons. “We saw Donald Trump on the news — the immigration issue,” he said. “And we’d heard rumors about tunnels and people jumping the wall.”

Inaoka turned onto a muddy dirt road that runs parallel to the border wall. We pulled up to a small dwelling whose northern edge shares a boundary with the border. As we spilled out of the car, we were greeted by a pack of children who surrounded Ushiro with shouts and hugs. Behind them was Esther Arias Medina, a steely Mexican matriarch who has lived on this land as long as she can remember — certainly long before a border wall ever materialized.

When the artists knocked on her door and asked for permission to build a treehouse in the lone pepper tree that inhabits her tiny yard, she said, “I didn’t think about it. I just said yes.” The children, she added, adore it.

We followed the kids to the back, where another member of Chim Pom, Ellie, who doesn’t use a surname and is the only woman in the group, waved hello from her perch in the treehouse.

Ellie’s own immigration troubles have given the collective a personal reason for creating a piece about the border.

In 2012, the artist, who also works in television, flew to Hawaii for a shoot with a Japanese video crew. Ushiro said that as a gag a member of the TV crew checked off a box on a visa waiver application stating that he had been involved in terrorist activities. As a result, the entire crew was banned from entering the U.S. and since then, Ellie’s applications to enter the U.S. have been denied.

The treehouse is as close as she’ll get to the U.S. for now. And the piece nods to this closeness: Its exterior is emblazoned with a sign that reads “U.S.A. Visitor Center.”

“What is the purpose of a visitor center?” Ushiro asked. “Parks like the Grand Canyon have visitor centers. [People] might not be able to go in, but they can see it from the visitor center. Ellie can’t go into the U.S., so she sees it from here.”

Based in Tokyo, the six members of Chim Pom have been working together for more than a decade, frequently taking on issues of politics and environment — often in wry ways.

They came to prominence in 2006 with an installation called “Super Rat,” which featured taxidermied rats from the city’s Shibuya District — some of which have developed an immunity to poison — painted to resemble the Pokemon character Pikachu.

In their ongoing piece “Don’t Follow the Wind,” the collective traveled into the exclusion zone around the site of Japan’s Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster and installed an art exhibition featuring works by various international figures including Chinese dissident artist Ai Weiwei, photographer Taryn Simon and Internet pranksters Eva and Franco Mattes. The installation will not open to the public until the area around Fukushima is declared safe for human settlement. That could mean decades.

“We are interested in invisible worlds,” Ushiro said of the piece. “This problem is long-term and it’s global and no one knows when Fukushima will be open again.”

The treehouse project began last summer, when four members of Chim Pom, along with a fellow artist, took a drive along the U.S.-Mexico border from Mexicali to Playas de Tijuana looking for something, anything, that might spark an idea for an installation or a performance.

In Colonia Libertad, they came across Arias’ singular home. “I’d never seen such a crazy house,” Ushiro said. “The landscape is really beautiful — you can see so much.”

That landscape includes the vast architecture of U.S. security theater.

From the treehouse’s northern window, it is possible to take in the sight of an unusual no man’s land: Several hundred feet north of the wall that marks the border is a second fence on U.S. territory. The fence creates a narrow corridor along the border that is closely monitored by the CBP. (I counted one helicopter, half-a-dozen trucks and one four-wheeler in the course of an afternoon.)

Chim Pom’s treehouse — which could sleep two adults comfortably — offers a humorous counterpoint to this austere landscape.

Its interior is decorated with a jumble of objects: sketches, maps and works of great American literature, such as Mark Twain’s “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer” (in Japanese). On one side hangs a coyote pelt — a nod to the smugglers known as coyotes, who help spirit migrants across the border, but also to famed conceptualist Joseph Beuys, who once locked himself in a Manhattan gallery with a wild coyote as a work of performance.

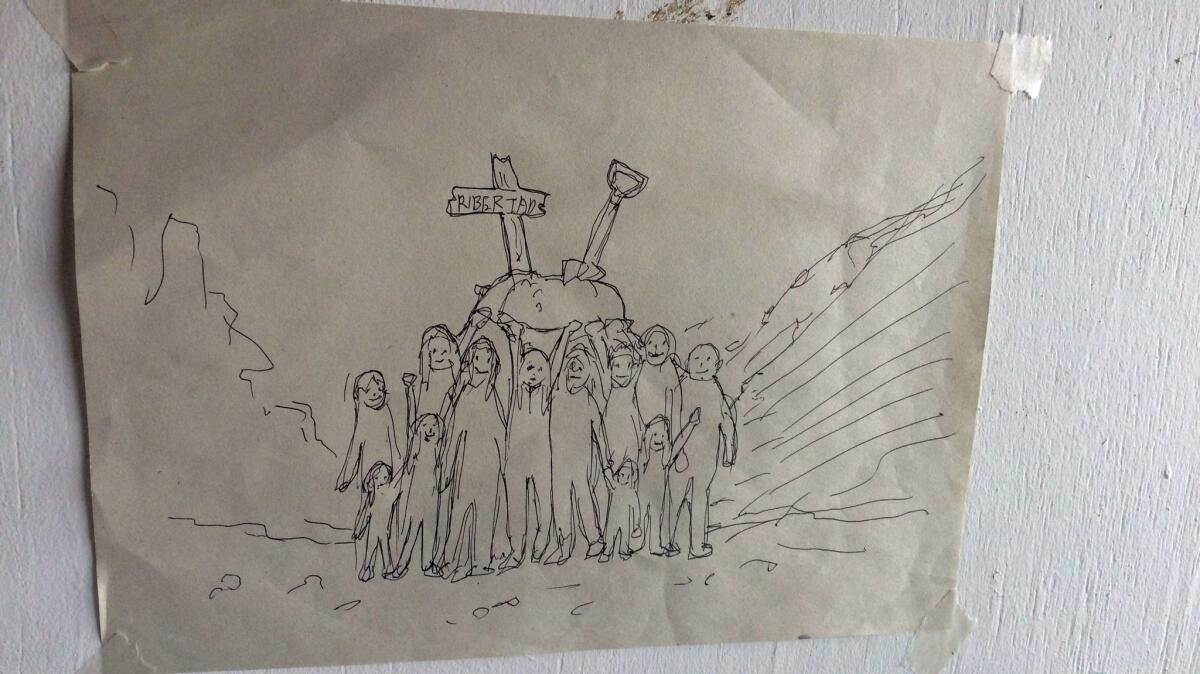

In addition to the treehouse, the artists created a small plastic sculpture of a grave titled “Libertad” (Liberty), which they placed on the U.S. side of the border as part of a short performance.

Late in the afternoon, the rain clouds parted and the border was suddenly bathed in misty light. Two stray dogs trotted through the no man’s land on the U.S. side, oblivious to the bureaucracy of international borders. Ellie gathered the Arias kids, along with their cousins and friends, to help carry the sculpture down the hill in a squealing, chaotic procession.

At the chosen point, Fernando Arias, Esther’s son, clambered over the first border wall on Mexican land and arranged the piece on U.S. land, in the gap formed before the second fence — an action that earned him a quick blast of a Border Patrol officer’s siren. Arias quickly clambered back over the wall to Mexican territory.

The piece, Ushiro said, “is to make a grave for liberty on U.S.A. land.”

While the election has brought much talk of building a border wall, the reality is that in places such as Colonia Libertad, walls have been a reality for a decade (even as undocumented immigration has dipped). Sometimes this has put the Arias family in the middle of tear gas and pepper spray assaults from border patrol.

Yet as imposing as the walls appear, they are nonetheless permeable. The U.S. fence, with its dense metal weave and its crown of concertina wire, is full of patches where determined individuals have sliced their way through with wire cutters. Ushiro said that in his time working on the treehouse, he has seen a number of people make it through.

“Donald Trump can build the highest wall,” he said, “but it’s useless.”

Before us, a 7-year-old girl named Sol climbed the border wall as if it were a jungle gym. She sat on top and paused for a moment to look around.

Then she turned and asked me if I was from “el otro lado” — the other side. I nodded. She replied: “I know people there too.”

Sign up for our weekly Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

On Twitter: @cmonstah

ALSO

Studio Visit: Ingrid Hernandez, forging an artistic record of Tijuana’s impromptu settlements

An architecture school rises in Tijuana’s red light zone

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.