Arts Preview: Chicano art pioneer Frank Romero is still painting, still loves cars and still defends ugly palm trees

From the outside, the red warehouse on West Avenue 34 in Lincoln Heights looks like every other industrial building on the block — the sort of place that might deliver drilling and clanging. But slip past the front door and you are greeted by a wonderland of art.

Bright canvases are arrayed around the space in various stages of completion. Ceramic dog creatures peer out from vitrines. A neon sign dangles from the rafters, illuminating the words “Car Radio” and a stylized bolt of lightning — a ray of energy that seems to infuse the room with a crackle.

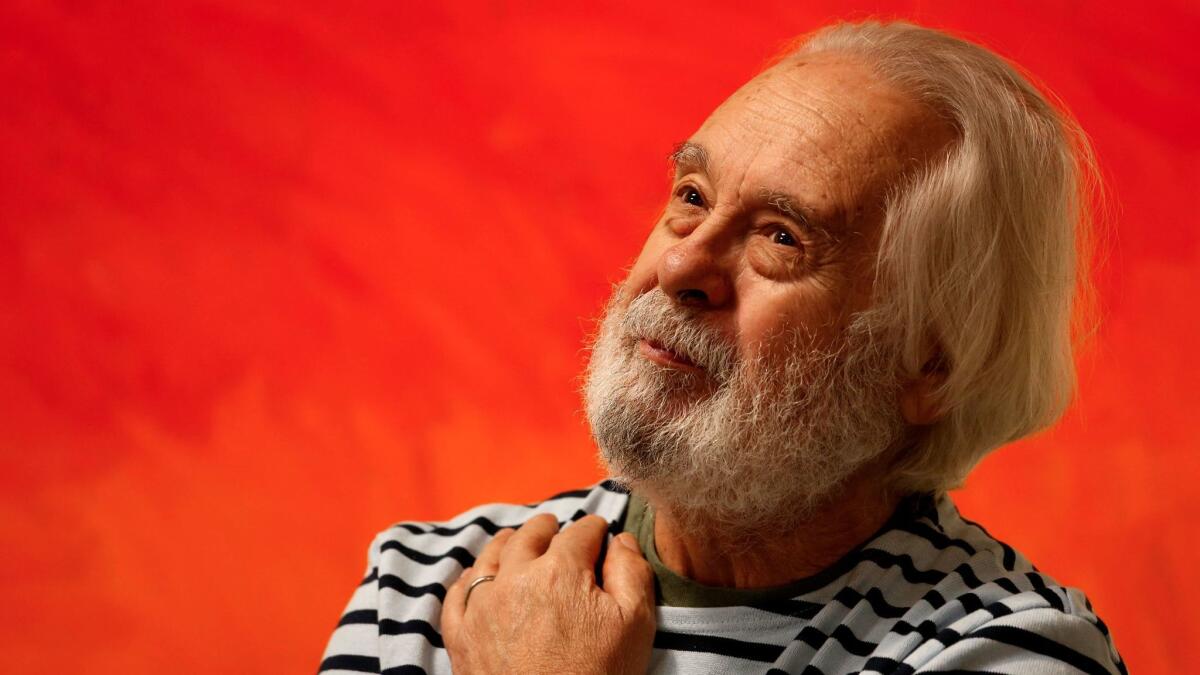

Sitting amid the clutter is painter Frank Romero, head covered by a luminous mane of white hair, working his way through a burrito from Chano’s.

“You have to try the Loco Burrito,” he advises me, as he cradles a swaddle of tortilla filled with beans and salsa. “It’s stuffed with a whole chile relleno.”

Romero is known for capturing expressive scenes of Southern California in his paintings: Looping freeways, historic architecture and streams of automobiles — the latter most famously rendered in a mural on the 101 Freeway in downtown L.A. He is the subject of a sprawling spring retrospective at the Museum of Latin American Art in Long Beach.

FULL COVERAGE: Spring arts guide 2017

We were very much involved in the cultural revolution that was happening at the time.

— Frank Romero, on his work with Los Four

“Dreamland,” as the show is called, brings together more than 200 works from throughout his career — including the socially and politically minded works for which he is renowned. Among these, the 1996 canvas, “The Arrest of the Paleteros,” which was inspired by police crackdowns on street vending — and now belongs to actor and comedian Cheech Marin, a collector of Chicano art.

“That’s only about 10% of what I’ve done,” Romero says of the show. “It was an impossible task.”

Born and raised in Boyle Heights, the artist has had a brush in hand from the youngest age. As a kid, he copied storybook art. In his teens, he attended a summer program at the Otis College of Art and Design, where he got to check out exhibitions by the likes of influential ceramicists John Mason and Henry Takemoto.

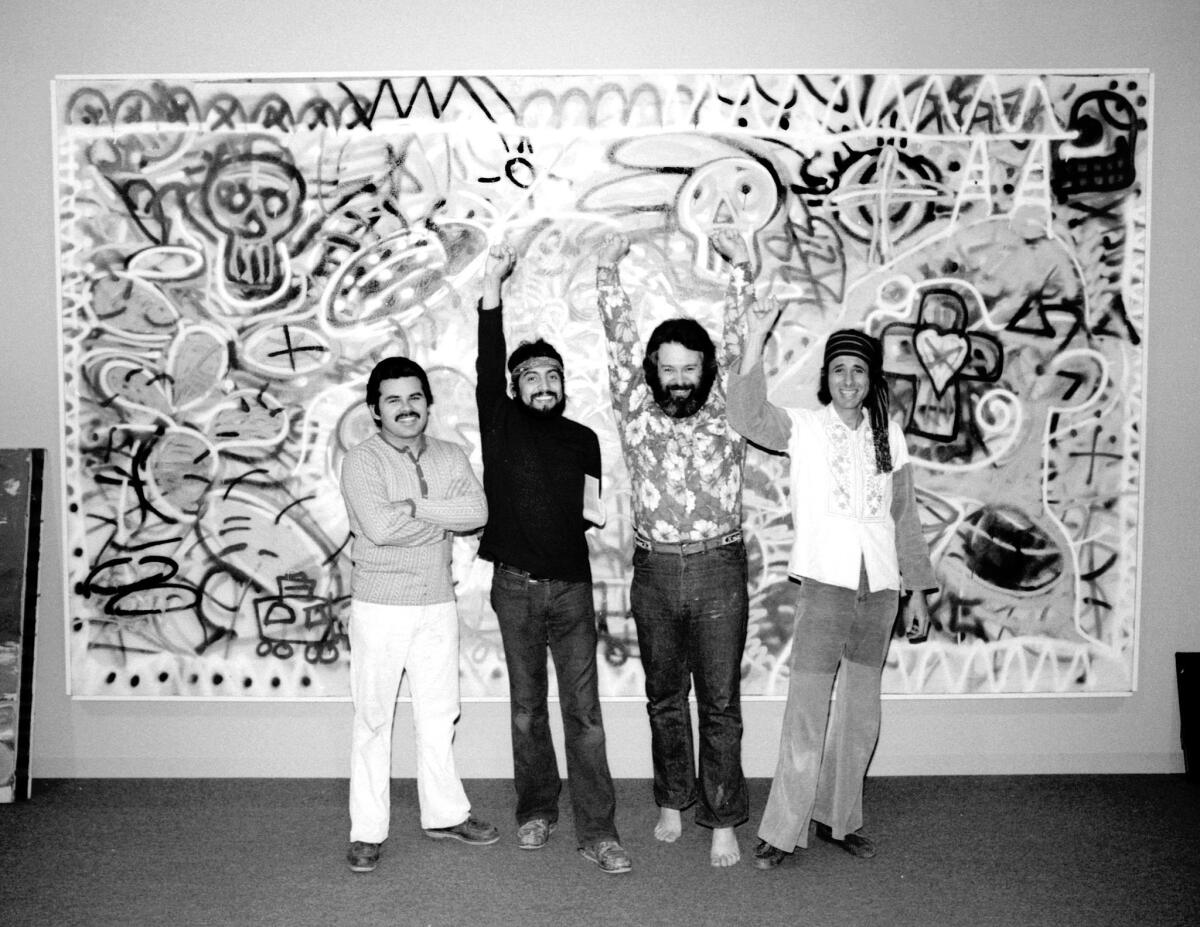

In the late 1950s, he enrolled at Cal State L.A. and became friends with the then-budding artist Carlos Almaraz — an encounter that would ultimately change the course of his life. With Almaraz, along with fellow Mexican American artists Beto de la Rocha and Gilbert Lujan, he formed the collective Los Four in the 1970s. In 1974, they became the first Chicano artists to have their work displayed at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Romero, 75, is as active as ever, painting daily, joyously munching on illicit chocolate chip cookies (he is diabetic), telling rambling stories and delivering deadpan one-liners with a twinkle in his eye.

“I pass for white,” he says. “You know you pass for white because when the police stop you, they call you sir.”

In this edited conversation, Romero talks about how film influenced his career, how he ended up working as a graphic designer in the studio of Charles and Ray Eames, and how he got caught up in the cultural revolutions of the 1960s and ’70s.

You grew up in Boyle Heights. What was the neighborhood like when you were coming up?

I grew up in the 1940s and ’50s. My mother was one of 14. We owned the town. I had hundreds of cousins. Everybody was a relative. For Thanksgiving, they would sit 15 at a table and we would eat in shifts all day long at my grandfather’s house.

To get downtown, you’d take the P Car on 1st Street or the R Car on Whittier. It’d cost 10 cents and we’d go to the Warner [Bros.] Theatre. I remember seeing “The King and I” there. For regular shows, we’d go to the Joy Theatre [in Boyle Heights] where they had serials. It was so noisy in there with the children that the owners would turn off the movie every 15 minutes to tell everyone to shut up.

Has film been important to your painting?

Film was important. I’ve done Fred [Astaire] and Ginger [Rogers] dancing. Audrey Hepburn and Anthony Perkins did a movie called “Green Mansions.” The movie wasn’t so hot, but the book was wonderful. I did a painting based on it.

I don’t know how to do anything else. I’ve done it all my life.

— Frank Romero, on his life as a painter

Why does film intrigue you?

They’re stories. Channel 5 was the major television station in those days and they showed old films. I grew up with these incredible films. “The Count of Monte Cristo” — I watched that like 55 times. “Rose of the Rio Grande,” “The Swiss Family Robinson,” all the “Rough Rider” films. I still watch Turner Classic Movies. It’s been an incredible influence on my life.

You took fine arts classes while at Cal State LA, but ended up working in graphic design for seminal figures such as Charles and Ray Eames. How did that come about?

I was going to school and someone said, “You should get this job with Lou Danziger” [a graphic designer who taught at Art Center School, later known as Art Center College of Design]. He sent me to Charles and Ray Eames. This was in the ’60s.

And I did graphic design for them — just picked it up. It was very exciting. I did materials for a Thomas Jefferson exhibition. I did film titles. I did posters. I did a film for the Polaroid Land Camera. The biggest thing I ever did there was a history of the computer for IBM.

I learned discipline there. I also had to take care of Ray Eames. She was an eccentric. They were strange people — very elitist. But they were the hot potatoes.

You also did a graphic design stint at A&M Records.

For Tom Wilkes, he was the big art guy there. There were interesting and strange people in that office. I met Karen Carpenter there. I met Phil Ochs there. Phil and I became quite close. It was “Brazil ’66.” It was Tijuana Brass and Herb Alpert. There was Ike and Tina Turner. I did liner notes and stuff like that. Eames was elitist, high design. This was musicians. It was more show business.

Following some of these jobs, you and Almaraz, Lujan and De La Rocha formed Los Four. How did that come about?

That was a political move. We’d sort of heard about the Chicano Moratorium [a 1970 protest against the Vietnam War] and there were the walkouts at Garfield High. And one day Carlos pulls up with this guy who had been publishing a magazine called Chisme Arte [a publication devoted to Chicano cultural issues]. That was Gilbert Lujan — and he had all of these radical ideas.

In those days, we were “Mexican American.” White people often would call me “Spanish.” If you were more liberal, you were Mexican American. The whole idea of being Chicano was very radical.

We decided we would do a Chicano art show. We saw the idea of being a collective as very interesting. Carlos was embracing communist ideas. And I was interested in the idea of working collectively. So we would have these horrible meetings at my house in Angelino Heights where we would scream at each other. [Laughs.]

Sign up for our weekly Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

How was Los Four a break from what you had done in the past?

I had been making elitist art. The kind of stuff you’re taught in art school. There was a Picasso-esque thing going on. I’d studied with [Italian painter and muralist] Rico Lebrun and Herbert Jepson from the Jepson Art Institute. It was very academic.

But Los Four — we were getting involved with idea of being Chicano. I was doing protest art. Carlos was working for Cesar Chavez. Beto and Gilbert got together with [painter] Gronk [Glugio Nicandro, a member of the art collective Asco] and they started a Day of the Dead parade in East L.A. We were very much involved in the cultural revolution that was happening at the time.

We would do things like make one giant painting collectively. There’s one of those paintings in the show. We were doing murals. It all became part of history. Then the City Council wouldn’t let you paint a mural without their approval and that was the end of the mural movement.

Your work has continuously featured iconic aspects of Los Angeles: Palm trees, cars, freeways. What intrigues you about these symbols?

It’s so much Los Angeles. My father loved to drive. I grew up in a car driving everywhere. That’s what I know about California. Cars were a part of the culture. That’s all you talked about as a young man. Gilbert and I talked about it a lot.

Carlos used to say that palm trees were so ugly, but they’re all I’ve ever known. I don’t know a Dutch elm from a maple.

In an interview, you once described yourself as a historian. Why?

It’s all stories. There’s a painting of a bonfire in the show [“Bonfire at Evergreen Playground,” 2016]. That was from the ’40s and ’50s. Every Halloween the city of Los Angeles would build a pyre of wood and then burn the whole thing to the ground. Every Halloween! You wouldn’t do that now because of fire hazards and pollution. But that was a story.

And there’s the death of Ruben Salazar [the journalist killed by sheriff’s deputies during the Chicano Moratorium]. I didn’t go to the Chicano Moratorium because I had a 3-year-old child, but that was a story. I was there when they closed Whittier Boulevard to cruising. That also became a painting. That was my first major piece.

But basically, that’s what I do: I tell stories.

Does Los Angeles still hold inspiration for you as a painter?

I like L.A. It’s easy to live here. Now I live in France half the year, but that’s a different situation. I’ve been in L.A. so long and I’ve done so much. I’m the kid who helped save the Watts Towers from Mayor [Sam] Yorty. I was 19 and I was hired to sit in front of the Watts Towers to collect money for the cable tests to prove that the towers could stand.

In those days, we were 'Mexican American.' White people often would call me 'Spanish.'

— Frank Romero, on the identity politics of the '60s

Do you still paint every day?

I don’t know how to do anything else. I’ve done it all my life. Before you walked in, I painted that orange background and I’m going to draw a horse on it. That one’s in oil. For giant paintings, I do acrylic.

I’ve done everything at some point. I tell everyone I’m self-educated, but it’s a lie. I’m old enough now that I can lie and change the stories and make them up.

+++

“Dreamland: A Frank Romero Retrospective”

Where: The Museum of Latin American Art, 628 Alamitos Ave., Long Beach

When: Through May 21

Info: molaa.org or (562) 437-1689

See our complete guide to spring arts events in L.A.

ALSO

International art invades the suburban Coachella Valley: The best of 'Desert X'

Margaret Atwood brings back 'Angel Catbird' and looks ahead to 'The Handmaid's Tale'

What finally broke the 'no Chicanos' rule at the reemergent Museum of Latin American Art

Carlos Almaraz's time is coming, nearly 30 years after death

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.