The steely art of Beatriz Cortez imagines otherworldly utopias at Craft Contemporary

If a group of ancient Mayan builders were to craft a space station that allowed them to inhabit other galaxies, what might it look like?

Perhaps it would contain a geodesic dome crafted out of scrap auto body parts. And an illuminated garden lab bearing seedlings of indigenous American plants such as quinoa, chile peppers and corn. To water those plants, its infrastructure might include a metallic water tower — one whose frame is inspired by the architecture of talud-tablero pyramids, the ceremonial structures of Mexico and Central America that feature several broad tiers. Maybe, just maybe, it would feature as mascot a charming adobe dog.

For the record:

11:50 p.m. May 9, 2019An earlier version of this story said Sheboygan was located in Michigan. It is in Wisconsin.

That is the world conjured by artist Beatriz Cortez in her installation “Trinidad / Joy Station,” now entering its final days at the Craft Contemporary museum in Los Angeles (formerly the Craft and Folk Art Museum). Her solo show — the first by a Salvadoran artist at the museum — imagines a space station, the ultimate architecture of survival, through a distinctly indigenous lens.

“I’m interested in including that,” she says, “indigenous knowledge that is about how to survive.”

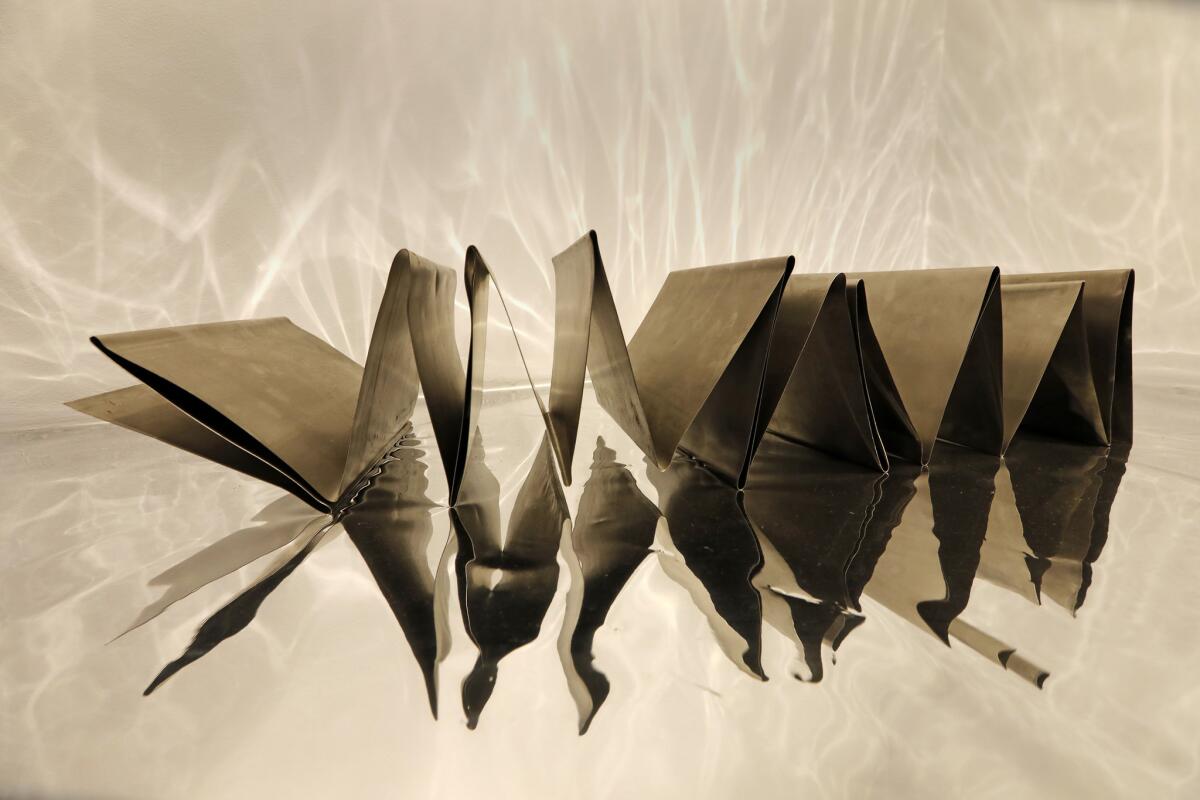

Cortez’s chosen material is steel, which she welds herself into structures that are often inspired by architecture and the social and political circumstances that shape it. But even as her pieces evoke the space age, they also feel resolutely handmade. Metal sculptures bearing imperfect seams feel as if they are brought together with needle and thread instead of a MIG Welder.

“I love making pieces with steel that are stitched together,” she says. “They enter a conversation about gender, labor and how people assume that men make things with steel, while women stitch. … When I’m welding, I imagine myself a seamstress.”

REVIEW: Graciela Iturbide’s legendary eye and arresting photos of Mexico »

It’s important, she says, for the viewer to see her hand in the work — to show the labor.

“I can’t talk about labor as an anthropologist,” she says. “The only way I could do that was to embody it — to build things myself.”

In fact, the only thing she didn’t make at the Craft Contemporary is the dog, along with an additional platform made out of adobe bricks — both part of a garden installation titled “Nomad 13” that she built with L.A. artist Rafa Esparza, a friend and collaborator known for employing handmade mud bricks.

“Nomad 13” provides a stark juxtaposition of materials and styles: Esparza’s earthy adobe platform bears a hexagonal steel frame by Cortez that is laden with rows of amaranth, sorghum and sage seedlings, among other plants. In this space station, technologies, histories and materials commingle effortlessly.

“She has so many layers and meanings and references in her work — these histories that are repressed that she wants to address,” says Holly Jerger, who serves as exhibitions curator at the Craft Contemporary. “But she also has this rich, poetic sense of materiality. She can bring all of these complicated larger concepts into these lush materials.”

On Sunday afternoon, the last day of her show, Cortez will give away the plants that have been growing in the gallery since her exhibition opened in late January.

“We thought,” she says, “it would be a way to multiply the joy in gardens throughout L.A.”

On a cloudy weekday morning, I find Cortez in her Lincoln Heights studio, an old commercial storefront off of Main Street. The hour is early but she is energetic — sharing accounts about Mayan village life, welding, philosophy and the sound of the freeways in Phoenix, the city where she first lived when she moved to the United States.

“If you sit there, they sound like the ocean,” she says. “I was coming from the tropics, with the ocean, and was going to the desert. … I did not appreciate the desert until many years later. I missed the green.”

Cortez’s studio is barren of any objects — except for a couch, a shelf and a small desk. Her sculptures are all on display, either at the Craft Contemporary, or in one of various ongoing group exhibitions around the country: Ballroom Marfa in Marfa, Texas, the Kohler Arts Center in Sheboygan, Wis., and the Queens Museum and the Socrates Sculpture Park in New York.

REVIEW: Michael Rakowitz remakes looted Iraqi antiquities with a modern message »

This follows appearances in the Hammer Museum’s “Made in L.A.” biennial in 2018 and the California Pacific Triennial at the Orange County Museum of Art the year before that — as well as regular exhibitions at Commonwealth and Council, the Koreatown gallery that represents her.

If it seems as if Cortez, 48, is making up for lost time, in a way, she is.

Born and raised in El Salvador, she immigrated to the U.S. in 1989, a few weeks shy of 19. At the time, the Salvadoran civil war was raging and fighting regularly spilled into the capital of San Salvador, where Cortez and her family lived. On Nov. 16 of that year, six Jesuit priests at a local university were executed by an elite army battalion. The Jesuits had supported a settlement between the government and the guerrillas; in response, the military declared the university a “refuge of subversives.”

Cortez at the time was an art student who had studied at Jesuit schools almost all of her life. Four days after the killings, she was on her way to the U.S. with a family friend — eventually landing in Phoenix to join a brother who was already living there. For the journey, she took only her clothes and a handful of seashells. She has included these in the installation at Craft Contemporary.

“They raise the question of, ‘What would you take if you left Earth all of a sudden?’” she says. “If you are an Angeleno, you ask the question, ‘What would you take if there is a fire?’ You really have to let go of possessions. What the 19-year-old me who left El Salvador wanted to take were these seashells that I’d been painting.”

There is something interesting about metal that it is so strong, but you can turn it into liquid and make it malleable.

— Beatriz Cortez

The story that follows is one that is familiar to refugees fleeing violence: moments of relief paired with moments of intense isolation and frustration. Taking any job she could get to help make ends meet. In between, trying to make time to study. It was difficult. But in the process, she also encountered strangers who showed her tremendous kindness — such as the art teacher who took her on excursions to study landscape.

“We would go to the river and look at the way the sun looks on the rocks,” recalls Cortez. “If there was an eclipse, it was like, ‘Let’s look at the eclipse, but through the leaves.’ … She was so great to me. She healed half of me.”

Out of that early struggle has come tremendous achievement. Cortez ultimately got her PhD in Latin American literature at Arizona State University. In 2000, she moved to Los Angeles to teach in the Central American Studies department at Cal State Northridge, the first department of its kind at a U.S. university. Now she leads classes on Central American novels, art and film.

But even as she spent more than a dozen years delving into literature, politics and philosophy — she is an avid reader of post-structuralists such as Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari — she has always thought about the path she gave up the day she plunked those seashells in her bag and fled San Salvador. So, about half a dozen years ago, Cortez went back to school to study visual art. In 2015, she received her master’s in fine arts from CalArts.

ALSO: Artist Jaime Hernandez reunites his ‘Love and Rockets’ women, but loves only one now »

She produced her first major work in steel shortly after graduating: a geodesic dome titled “Black Mirror” that she presented at Cerritos College Art Galleries in 2016, an installation that explored the politics of vocational work. The material spoke to her for the ways it can be manipulated.

“There is something interesting about metal that it is so strong, but you can turn it into liquid and make it malleable,” she says. “If you mess it up, you can patch it. It symbolizes our society’s modernity, but it also symbolizes its weakest spot. When we say, ‘This is made of steel,’ we imagine it to be super strong. But things made of steel can collapse. Steel is organic.”

And steel has become her chosen raw material for sculptures and installations that explore other difficult questions.

In her installation at OCMA for the triennial, she built a porch inspired by the work of Dan Montelongo, a homebuilder of Apache Mescalero descent, who used indigenous rock building techniques on Craftsman homes in the Los Angeles area in the early 20th century. He helped shape the Los Angeles landscape and was subsequently forgotten.

In 2017, she showed “Memory Insertion Capsule” at UC Riverside as part of the Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA exhibition “Mundos Alternos: Art and Science Fiction in the Americas.” That work explored the appalling history of an early 20th century L.A. eugenicist who promoted forced sterilization.

Cortez’s current exhibition at Craft Contemporary features a series of furnishings made out of chain-link fence that has been woven with strips of sparkling mylar blanket, the kind used by marathon runners — and Central American migrants held in immigration detention centers. Cortez says she was inspired to make the piece after learning about the Japanese American internees who created a garden at the Manzanar internment camp during World War II, a bit of grace during a dire moment in American history.

“It’s my way of turning the only materials that the children in cages have into a cosmic, magical space,” she says. “With the same materials, another world is possible.”

In 2015, during one of the presidential primary debates, Florida Republican Sen. Marco Rubio said that the U.S. needed “more welders and less philosophers,” failing to realize that in someone like Cortez, the two fields might just overlap.

“I’m a welder-philosopher,” she says. “I make my work with steel and also with philosophy.”

+++

“Beatriz Cortez: Trinidad / Joy Station”

Where: Craft Contemporary, 5814 Wilshire Blvd., Mid-Wilshire, Los Angeles

When: Through Sunday; plant giveaways will take place starting at 3 p.m. Sunday

Info: cafam.org

[email protected] | Twitter: @cmonstah

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.