Composer Andrew Norman’s imagination has taken residence

BROOKLYN, N.Y. — Inside his airy loft last week, Andrew Norman was nervous as he talked about his childhood and God. The 32-year-old composer, a finalist this year for the Pulitzer Prize in music, spoke in anxious halts and starts about his upbringing in “a strict religious environment” in Modesto, where his father is a pastor at an evangelical church.

Norman was tense because he rarely spoke about his personal life and wasn’t quite sure what to say. And since he had left home as a teenager to study music at USC, he had wrestled with his faith, an inner conflict heard in his music, notably his searing, Pulitzer-nominated work for violin, viola and cello, “The Companion Guide to Rome,” a portrait of nine churches and saints.

But when Norman was honest with himself, which he seemed to be nothing but, he knew the seeds of his calling were planted at home. “It was common to see the divine in everything,” he offered. “Things happen, and there’s a natural gratefulness for them. We were good at looking at beauty in the world. I don’t know whether it’s God or what, but it still opens you up to a lot of stuff.”

Although his parents aren’t musicians, they often played an album of baroque music around the house. “I was 5 years old, and this music made me cry every time,” Norman said. “It was an aria from Handel’s ‘Xerxes’ and Bach’s E-major violin partita. I think I am a composer because music did this to me when I was a kid. I would love to be able to write things that do this for other people because it’s really powerful.”

One person enraptured by Norman’s music is Jeffrey Kahane, music director of the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra. This year Kahane chose Norman as the orchestra’s composer in residence, a three-year post. Norman will write a new work for the orchestra and give music talks at schools and concert halls around the area.

On Oct. 6 and 7, on a program featuring Ravel and Beethoven, the orchestra will play Norman’s “The Great Swiftness,” a vertiginous work composed in 2010. Strings and woodwinds swoop and swirl, as if tracing the abstract wings of the magnificent Alexander Calder public sculpture, situated in Grand Rapids, Mich., where Norman was born. His family (he has an older brother) moved to Modesto when he was a toddler.

Kahane said he was “blown away by the imagination” in Norman’s music, which has been performed by orchestras in the U.S. and Europe and laureled with countless awards. Although, with a chuckle, Kahane said he couldn’t describe it. “I can come up with adjectives like ‘colorful,’ ‘witty,’ ‘affecting,’ but none of those grasp and communicate the essence of what makes his music unique.”

Last year in a review of Norman’s “Try,” performed by the Los Angeles Philharmonic, conducted by John Adams, Times critic Mark Swed went along for the ride. “There is no end to the odd sounds Norman entices from a fairly conventional chamber ensemble,” he wrote. “Strings buzzed like insects. Winds burst in with pinpoint dabs of color.”

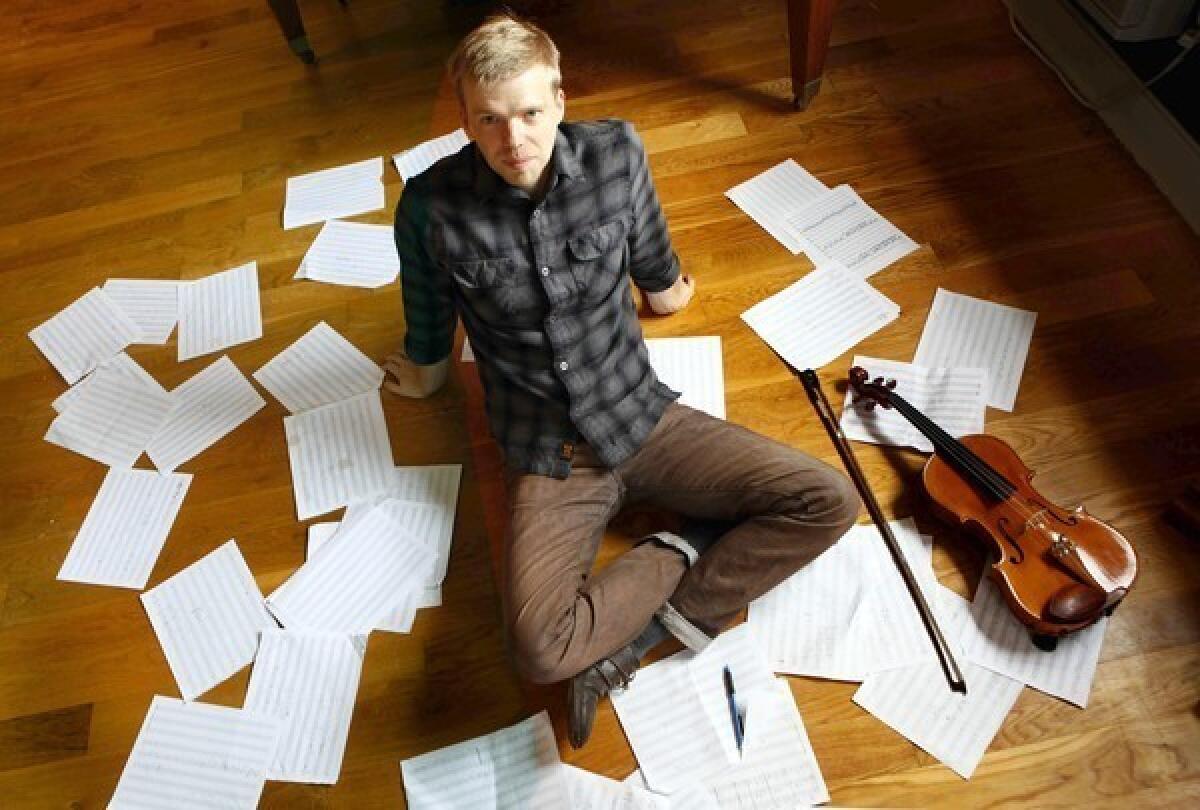

Norman has an elfin demeanor thanks to his trim physique, fair skin and blond hair, traits of his Swedish heritage. But his boyish appearance is counterbalanced by a fervid intellect and piercing wit.

In his loft, Norman fidgeted at a long wooden table, covered with sheets of music. He was working on a piece for the New York sextet yMusic, which champions new composers. “But as usual, I am horrendously behind,” he said. “The premiere is in two weeks, and this is still a mess of sketches. Oh, I am not in a happy place.”

He walked across the room to his piano. He wanted to demonstrate the closing bars of “Try,” in which a single C-sharp flares into one wrong chord after another.

“The music is looking for something it hasn’t found yet,” Norman said, his fingers pouncing on the keys. “You’re hearing the music trying to get off that C-sharp, exploring different worlds, trying to find the right resolution. It reflects a kind of unsettledness. It’s in conflict with itself.”

Martha Ashleigh, Norman’s piano and composition teacher when he was a teenager, said Norman, despite his association today with young composers who scorch musical categories, harbors another side.

As a teen, she said, “Andrew could play a schmaltzy Rachmaninoff prelude and have everybody in a room get so quiet it was just unbelievable. You would be crying because he touched your soul.”

Ashleigh chided Norman, who also plays the viola, for the erratic leaps in his current works. “He wants to get away from melodic control; he’s fighting it,” she said. “But it’s down deep inside of him, and I think he just needs to let it go.”

Norman said the piece he is composing for the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra, to be performed this spring, is inspired by the M.C. Escher illustration series “Metamorphosis.” Norman is obsessed with architectural patterns and is electrified, he said, by geometric patterns evolving into birds and fish in Escher’s drawings.

“I love the idea of one sound transforming itself into something else and watching that process unfold,” he said. “It’s like a dream where just as soon as you can grab onto something and say, ‘This is this,’ it’s already on its way to being something else.”

For days after the interview in his loft, Norman sent emails, refining his comments. In one, he admitted, “I’m not yet the composer I want to be. It’s going to be a long journey for me with lots of dead ends and confounding turns, but every once in a while I catch a glimpse of where I’m going and why, and that glimpse is enough to keep me making music and moving forward.”

MORE:

CRITIC’S PICKS: Fall Arts Preview

TIMELINE: John Cage’s Los Angeles

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.