An edgy opera company gives it a go in Los Angeles

With the sound of brass instruments coming from above, scenes of wreckage on the floor and an array of abstract sculpture in between, this warehouse space captures music, art and chaos all on a collision course. That’s a fitting combination for a performance piece about post-Katrina New Orleans, but director Yuval Sharon wants to be clear: “Crescent City,” the ambitious and unconventional “hyperopera” that opens this week at Atwater Crossing, both is and isn’t about the hurricane-ravaged city.

“It’s a little bit ‘Invisible Cities,’” he says, referring to Italo Calvino’s lyrical, abstract novel. “That allows it to be not just about New Orleans, or a documentary of the city, but about humanity after a disaster — in a mythic or archetypal way.”

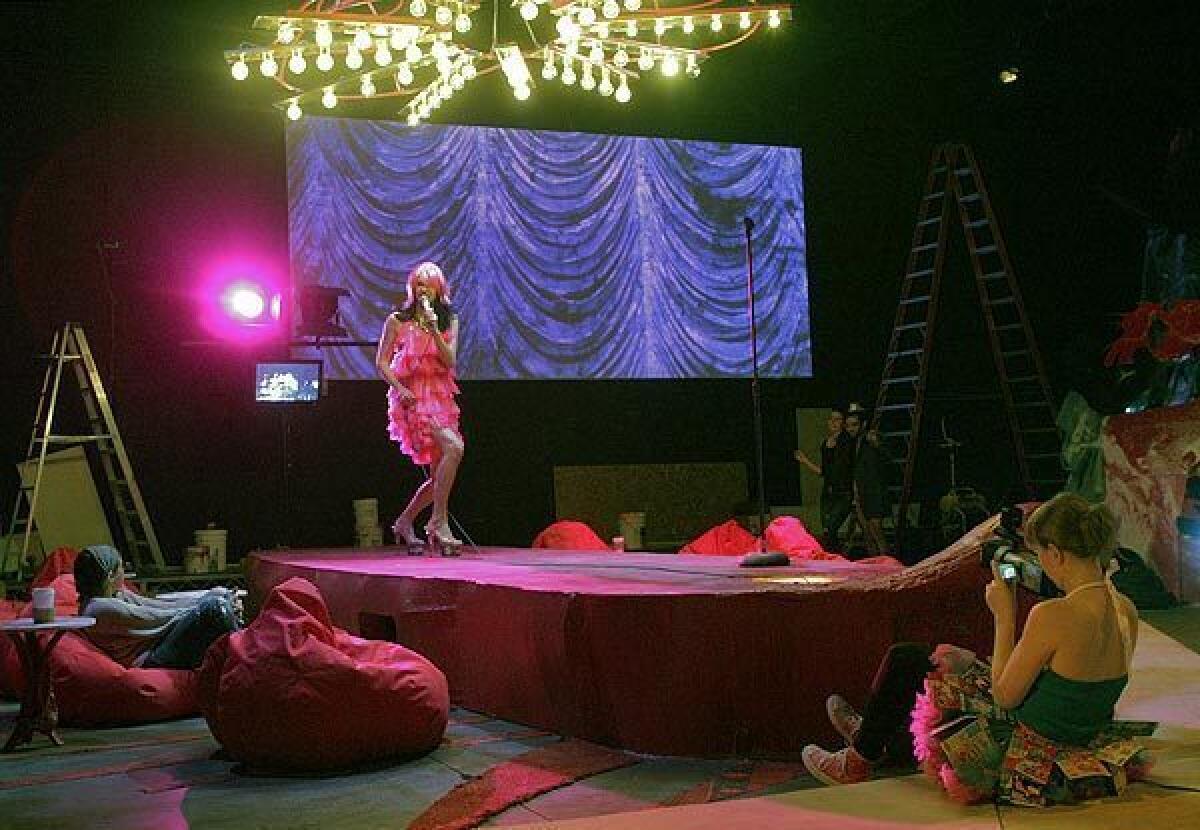

Sharon walks through the studio, pointing out the six sets designed by local visual artists, which include a cemetery, a hospital and an otherworldly dive bar. “Crescent City” opens after a devastating flood: “There are very few people left,” the elfin, enthusiastic director, 32, explains. “One policeman, two nurses in charge of the hospital, a few hangers on, and a group of revelers celebrating the end of the world. The whole city is teetering between life and death.”

One character is based on the 19th century voodoo queen Marie Laveau, who appeals to the voodoo gods to save the city. They refuse — unless she can find a person of virtue to justify the salvation. “So ‘Crescent City,’” Sharon says, “is a travelogue to find that one decent soul.”

Despite what looks like a jumble of visual idioms, the whole piece will — its creators hope — come together on opening night. “This is one of those idealistic things that is not imploding,” says the piece’s composer, Anne LeBaron of CalArts. “I really think the gods are smiling on us. I was actually afraid — if they were angry, they could do so much damage.”

“Crescent City” is the first major local offering helmed by Sharon, a Chicagoan who first came to town by way of New York while serving as assistant director for Achim Freyer’s “Ring Cycle” with the Los Angeles Opera. After years living in Brooklyn, he relocated to Los Angeles, after falling in love with the sense of possibilities he sees here and its fascination with the new. “L.A. just feels like a lot of freedom and potential. There are great things being done here, but there’s room for more.” The opera is a coming-out party for his company, the Industry, devoted to adventurous work.

The company hopes to produce operas annually, Sharon said. “Each one should be an experimental process: The process is more important than having a narrative or not having a narrative. The creation of the opera is the experiment.”

While serving as project director of New York City Opera’s VOX series, which workshops new, often edgy operas, he developed pieces that excited him. “People would come from all over the world to see them, and would say, ‘Good work,’ but wouldn’t put them on.” He grew frustrated, too, at how the expense of spaces in New York made it hard for operas to grow into productions there.

One of the works he developed there was a piece of LeBaron’s, then called “Wet,” which drew from her roots in Louisiana and its music — she’s a cousin of trumpeter Al Hirt. As it expanded and its name changed, poet Douglas Kearney, also of CalArts, wrote a libretto. When Sharon put on a one-off of Veronika Krausas’ “The Mortal Thoughts of Lady Macbeth,” at the dance hall Fais Do-Do, he realized the audience was here for avant-garde work, and that “Crescent City” would come next. It opens Thursday for a 12-performance run.

He realized, too, that spaces in L.A. could be a lot cheaper than in New York, though it took him a while to find the right one. “We went to the craziest warehouses and craziest industrial spaces in L.A.,” he says. “I thought, ‘Audiences will want to get in their cars and flee.’ ”

Atwater Crossing, a sprawling complex on the edge of the city, which houses the gourmet café Atwater Crossing Kitchen, production companies and the literary magazine Slake, seemed right. (Given Sharon’s energy level, easy access to espresso was clearly a major factor in the choice of location.)

As unorthodox as the story line, music and sets are, the relationship of the audience to “Crescent City” itself may be even stranger. Audiences can view the work from beanbag chairs in the set’s approximation of a dive bar, from what Sharon jokingly calls a skybox set over the action, or while walking along a pedestrian area along the edge of the stage. The latter option, he says, “allows you to look at it from the perspective of performance art or a gallery,” with a shifting point of view and accidental connection with other audience members.

It’s the kind of rethinking of conventional ways of doing things that Sharon and the gang at the Industry hope to pursue in future works. He’s aiming for what Richard Wagner called the Gesamtkunstwerk — the total work of art — but not tied, as it typically was for Wagner, to a single creator’s ego.

Laura Kay Swanson, a recent CalArts MFA grad and former professional opera singer, serves as Sharon’s partner in the Industry. “I’d always wanted the opportunity to make opera not just more accessible but really inclusive and appealing,” she says. “For someone who has never seen an opera, this is the show they should see. Producing innovative work that appeals to a wide audience is really my goal.”

His primary value, as he talks about the arts and world of performance, seems to be instability. It’s appropriate for a director whose latest work is a meditation on disaster, and where a $250,000 budget (from donors and a joint grant from the Doris Duke and Andrew Mellon foundations) requires a great deal of scrambling for everyone involved.

“Opera isn’t supposed to have a clear road map,” he says of a genre whose greatest virtue, he thinks, is in pulling music, theater and art into a whole. “How do these different arts come together? There shouldn’t be any set answer. That’s been an enormously exciting part of it.”

‘Crescent City’ Atwater Crossing, 3245 Casitas Ave., Los Angeles; 8 p.m. Thursdays-Sundays, through May 27: $25 to $75; Information: : https://theindustryla.org; Running time: 2 hours, 15 minutes.

ALSO:

Thomas Kinkade died of alcohol, Valium overdose

L.A. Philharmonic extends jazz contract with Herbie Hancock

Art review: Warhol odd man out in MOCA’s ‘The Painting Factory’

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.