Julius Caesar, young and gay: A groundbreaking 1971 opera gets revived for a new era

Lou Harrison, the beloved California composer, would have turned 100 this spring, and arguably the most important centenary event will come Tuesday at Walt Disney Concert Hall with a sold-out staged production of his long-evolving opera “Young Caesar.”

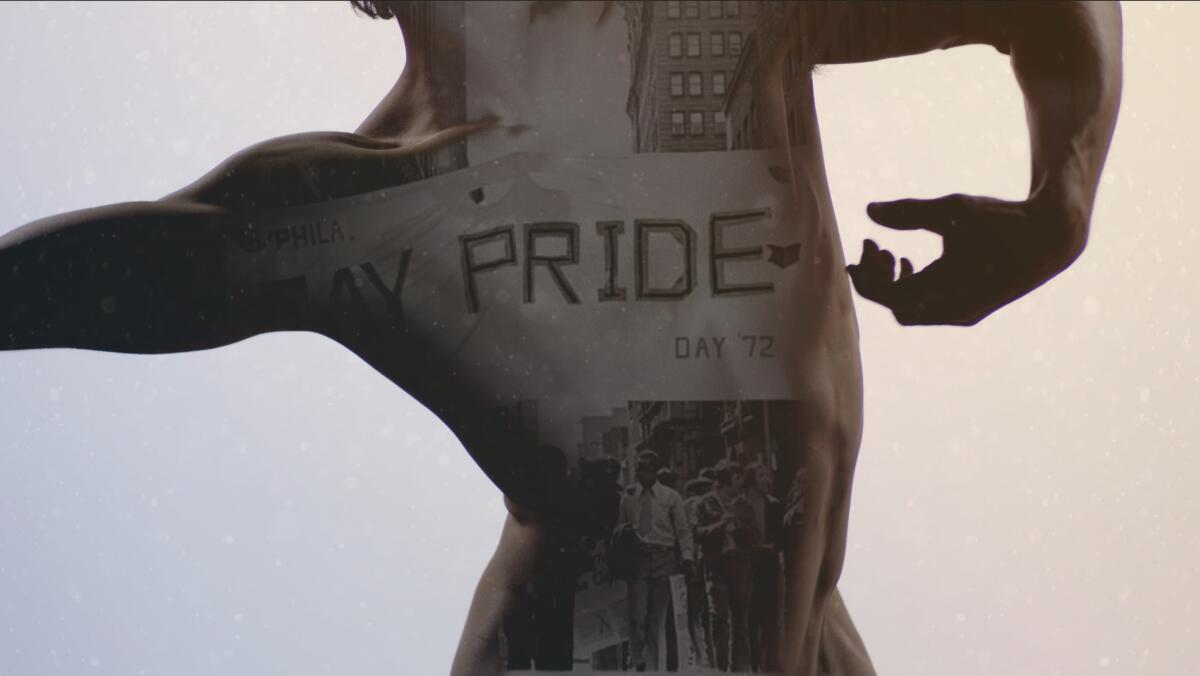

“Young Caesar” was especially dear to Harrison’s heart. When the Encounters music series in Pasadena asked for an opera, Harrison was at a loss for a subject until his partner, Bill Colvig, proposed in 1969 that he explore a gay subject. The result was what may well have been the first overtly male gay opera in history, complete with a love affair between the teenage Julius Caesar, as an emissary from Rome, and Nicomedes, the king of distant Bithynia, on the south shore of the Black Sea. It even had a gay orgy, depicted with puppets.

The opera was a testimony to Harrison and Colvig’s then-new love, speculates Yuval Sharon, the

The story derives from the Roman historian Suetonius. Sexual fluidity among young men in ancient times may have been more prevalent than in later centuries. Like most men of the Roman upper classes, Caesar had wives and children. (An adopted son became the Emperor Augustus.) Caesar later denied that he had an affair with Nicomedes, despite his long dalliance in Bithynia. Still, the opera is hardly an ahistorical fantasy.

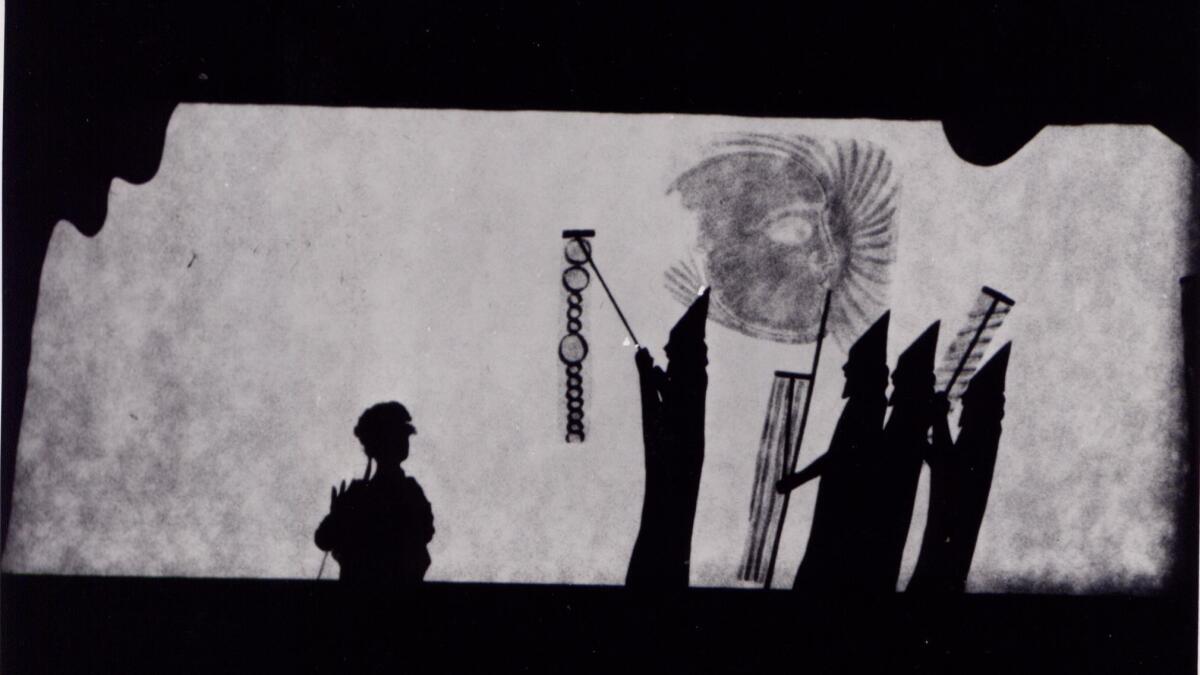

Heartfelt “Young Caesar” may have been, but a success it was not. It has suffered a long, tortured history. I reviewed its premiere at Caltech for the Los Angeles Times in 1971. Then it was a chamber opera for five players of mostly Asian or Asian-inspired instruments, plus the rod-and-stick and shadow puppets, singers and a narrator. I praised the considerable beauties of its instrumental music and set pieces but complained about the protracted recitatives, the “long, arid patches of spoken narration” and the “precious, self-indulgent libretto by Robert Gordon.” I concluded by grumping about “pervasive, embarrassing ennui.”

There was a subsequent performance in San Francisco, but Harrison and Gordon recognized the need for improvements. In 1987, the Portland Gay Men’s Chorus in Oregon commissioned a new version (with assistance from another beloved Californian, the patron Betty Freeman). Harrison added choruses, eliminated the puppets and revised the orchestration for Western (albeit equal-tempered) instruments. To judge from a video, this version lacked the charm provided by the puppets and Asian instruments and still dragged.

By 1997, I was director of the Lincoln Center Festival in New York, and I did a public conversation with Harrison. At the time, filmmaker and producer Eva Soltes told me Harrison was still eager to make “Young Caesar” into a successful opera. I commissioned Harrison to turn “Young Caesar” into a “real” opera, with consistent Western instrumentation and proper arias.

But the revision remained imperfect, due largely to Harrison’s unwillingness to trim Gordon’s libretto. After I returned to journalism and became a critic at the New York Times in 1998, my successor with the Lincoln Center Festival, Nigel Redden, tried to stage “Young Caesar.” My idea had been to enlist as director the choreographer Mark Morris, who loves Harrison’s music and has set many dances to it. I figured he would be sympathetic and that his name would attract audiences.

Morris declined, citing scheduling conflicts (though Soltes, now the keeper of the Harrison flame and director of the Harrison House artist residency and performance program, said Morris also felt the score needed improvements). Dennis Russell Davies was to have conducted the New York production, and according to Soltes, he suggested the choreographer Bill T. Jones as director — though Jones too was unwilling to proceed without alterations. His partner, Bjorn Amelan, worked up a revised, tightened version of the libretto, which Harrison refused to accept. Redden finally canceled the Lincoln Center project in 2001.

In 2007, four years after Harrison’s death, Opera Parallèle in San Francisco finally staged the Lincoln Center score, honoring the composer’s 90th birthday. This may have been the best version so far, but “Young Caesar” still suffered from dramaturgical clumsiness and excessive length.

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

So now we have yet another version, which sounds as if it will be much closer to what Redden and Jones were trying to achieve. Sharon first heard arias from the opera in New York 15 years ago. He has been discussing a new staging with Soltes (creative consultant for this production) for five years.

The new version has been compressed by a quarter — to 90 minutes, no intermission. With Gordon’s and Soltes’ eager acquiescence, Sharon and his conductor, Marc Lowenstein, worked with Bill Alves and Brett Campbell, authors of a new, definitive, critical biography of the composer. They cut down the recitatives and narration and some internal repeats and, adds Sharon, made tiny adjustments to the music to accommodate the shortening.

The instrumentation now comprises a 13-player Western ensemble and, especially for the scenes in exotic Bithynia, five obbligato Asian instruments and a full American gamelan, meaning a Javanese-style mostly metallic percussion orchestra made in America. (There are several replicas of the Harrison-Colvig original now; this one comes from South Dakota.) Sharon calls the new score a “hybrid” of the earlier versions.

Would Harrison have resisted the re-instrumentation and cuts? Will Harrison loyalists object to them? Soltes, Sharon and Robert Hughes, a longtime Harrison collaborator and conductor of the 1971 original Pasadena performances, think not.

“Lou liked to allow his interpreters a lot of leeway,” Hughes said in a recent phone interview from Emeryville in the Bay Area. Sharon added that by the 1990s both Harrison and Gordon had become more open to cutting both the words and the music.

The hope is that the new version will finally validate “Young Caesar” as an opera that other companies will want to perform. Certainly a Harrison clan of admirers and collaborators will congregate at Disney Hall on Tuesday, in celebration but maybe also in apprehensive expectation.

Rockwell was a Los Angeles Times music and dance critic from 1970 to 1972, and later a New York Times critic, correspondent, columnist and editor.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

‘Young Caesar’

Where: Walt Disney Concert Hall, 111 S. Grand Ave., L.A.

When: 8 p.m. Tuesday

Tickets: Sold out

Information: (323) 850-2000, www.laphil.com

Support coverage of the arts. Share this article.

ALSO

A critic’s take on the Tony Awards: What they say about American theater

Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Why his Los Angeles houses deserve a closer look

'The Other Mozart'? Her name was Maria Anna, and she dazzlingly comes to life onstage

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.