Review: LACMA’s uneven new Picasso and Rivera show reveals an unprecedented, must-see discovery

In 1915, Pablo Picasso acquired a small Cubist still life painted by his casual friend and acolyte, Diego Rivera.

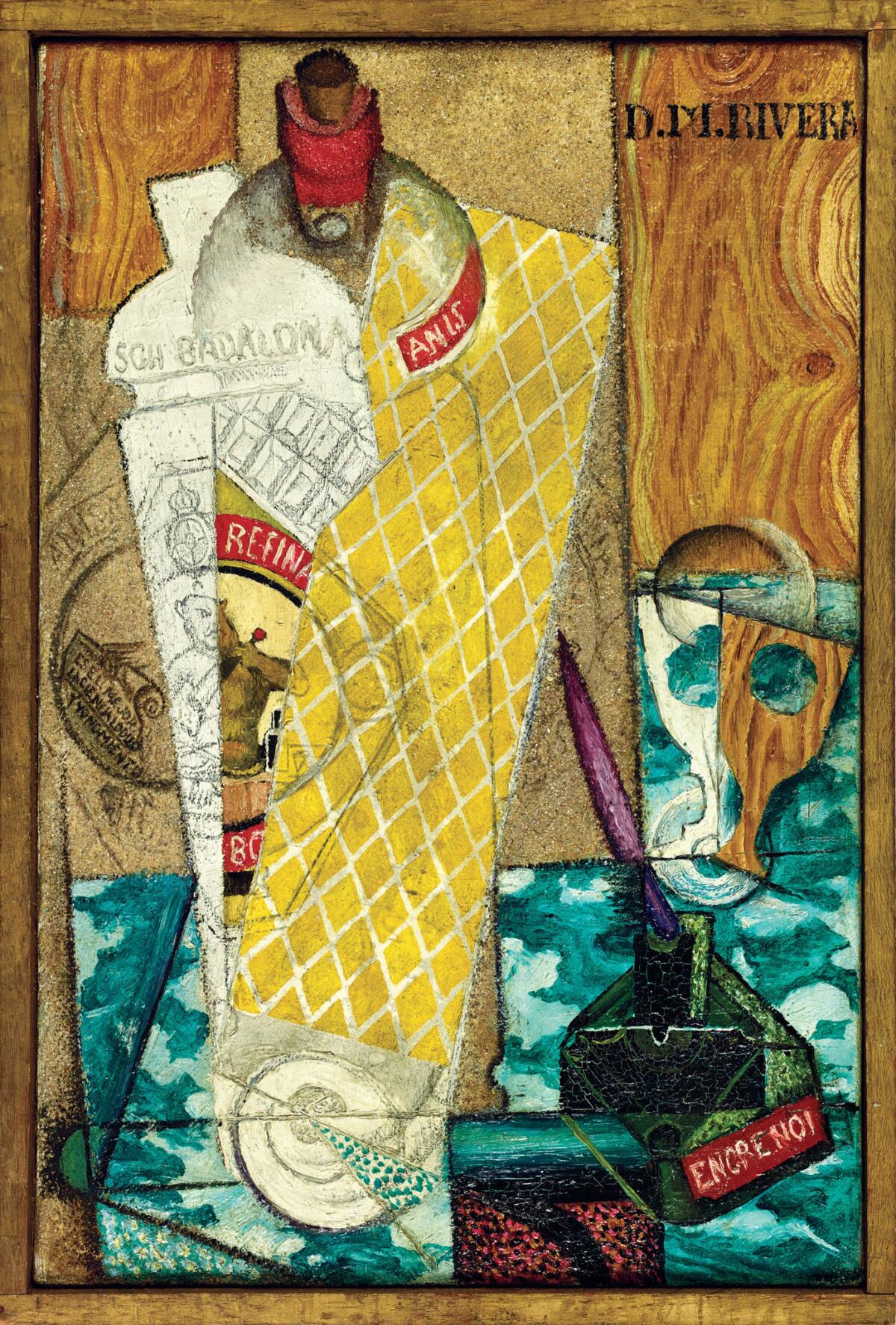

The young Mexican artist, 28, had been traveling through Europe and living in Paris for years, and he and Picasso were neighbors in Montparnasse. A small but powerful surprise haunts his little still life, on view in an unusual new exhibition about the dialogue between the two artists that opened last Sunday at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

The tabletop is covered by a turquoise-green decorative cloth, similar to the patterned designs Matisse was making after his return from Tangiers. In the center, a yellow, white and red bottle of sweet Anis liquor opens out like a Cubist fan, next to a triangular black inkwell pierced by the blade of a tall purplish pen.

Sand is mixed into some pigments. A technical experiment, the rough surface compares actual textures with illusionistic ones, like the painted wood-grain table that Rivera also surely borrowed from Picasso.

Amid the still life’s faceted planes, however, Rivera also painted something strange — one or maybe two wine glasses that overlap. One appears white (light reflected on glass), the other wood grain (the table refracted through glass); a mottled green circle of tablecloth pierces each. Their conjoined forms produce an unexpected double-image — not just wine glasses but a human skull.

The gesture is sly. Rivera’s painting knits together two robust traditions — a common European still-life symbol for life’s vanity, plus a distinctly Mexican version of the death’s head motif, which dates back before the European conquest to Aztec, Mixtec and even Mayan art.

Rivera’s home country, 5,000 miles from Paris, was then deep into a bloody peasant revolution — a convulsive civil war that would drag on for another five years. It was plainly on the artist’s mind.

Except for a brief 1910 visit, Rivera was absent from Mexico for the war’s duration. But the painter was no stranger to its long-simmering motivations.

He was born in the once absurdly rich silver-mining hill town of Guanajuato, scene of some of the most horrific abuses of the Spanish viceroyalty after the European conquest. The family’s house was just up the street from the market warehouse where the slain leaders of the 1810 Mexican War for Independence had their severed heads strung up by Bonaparte forces loyal to New Spain.

The small painting’s admixture of traditional and avant-garde French, Spanish and Mexican elements is thus remarkable and revealing. “Cubist Composition (Still Life With Bottle of Anis and Inkwell)” adds a subtle but inescapable political dimension to Cubism’s otherwise formal investigations, which focused on principles of representation and abstraction.

Here’s another surprise: The Rivera painting, which has remained in Picasso’s family ever since he acquired it a century ago, has apparently never been publicly displayed — or even published — before now. The LACMA exhibition will be seen only in Los Angeles and Mexico City (it travels to the Museo del Palacio de Bellas Artes in June), so don’t miss the unprecedented chance for a look.

Oddly, however, neither the object label nor the exhibition catalog mention the skull. Nor does either text offer any interpretation of what the picture might suggest.

Instead, the focus is fixed on details of the artists’ biographies — on how Picasso got the Rivera painting and what Rivera got in return — plus their formal experiments with materials and techniques for re-imagining representational painting. Both are important, but neither is enough.

“Picasso and Rivera: Conversations Across Time” is uneven that way. There are wonderful objects to see. But sometimes a viewer is left hanging.

Part of the reason is structural. The exhibition is organized like a graduate school art history lecture, where slides of different artworks are projected side-by-side to compare and contrast. The show juxtaposes actual paintings, sculptures and drawings, not photographs; but the binary system creates a closed loop that has trouble breaking out.

For instance, it’s easy to read visual similarities and divergences in the Cubist faceting of paired landscapes. Picasso’s earthy color and schematic architecture in a bracing painting from the crucial summer he and Georges Braque spent painting side-by-side in the French Pyrenees couldn’t be more different from the explosive burst of light in Rivera’s semi-rural scene, where the sun breaks through fog over a viaduct and factory smokestacks.

But the Rivera, painted in an industrializing town just outside Paris, is finally more closely informed by the work of Robert Delaunay than Picasso. The pairing is peculiar — as is the colorful little still life’s juxtaposition with a fine Picasso drawing in black ink and watercolor, when its vibrant palette owes so much to Juan Gris.

The show’s structural organization is reductive, simplifying art’s layered density. That’s counterproductive, working against the very complexity that makes Picasso and Rivera such brilliant, enduring artists.

In five sections, the show means to tell the story of the relationship between the two artists, as well as the relationship between the art of antiquity and their individualized forms of Modern artistic expression. The aim is not without merit.

Both artists began their training in tradition-minded academies — Picasso at Barcelona’s Academy San Fernando, Rivera at Mexico City’s Academy San Carlos. With great facility they both drew from plaster casts of Greco-Roman sculptures, as academies everywhere taught.

Picasso’s Venus de Milo drawing, done when he was about 14, focuses like a laser on her naked upper torso and perky bosom. Rivera’s, executed at about 16, shows the armless sculpture lying on its back on the ground — European Classicism toppled. Picasso the ladies’ man and Rivera the anti-colonialist are announced, at least in general terms.

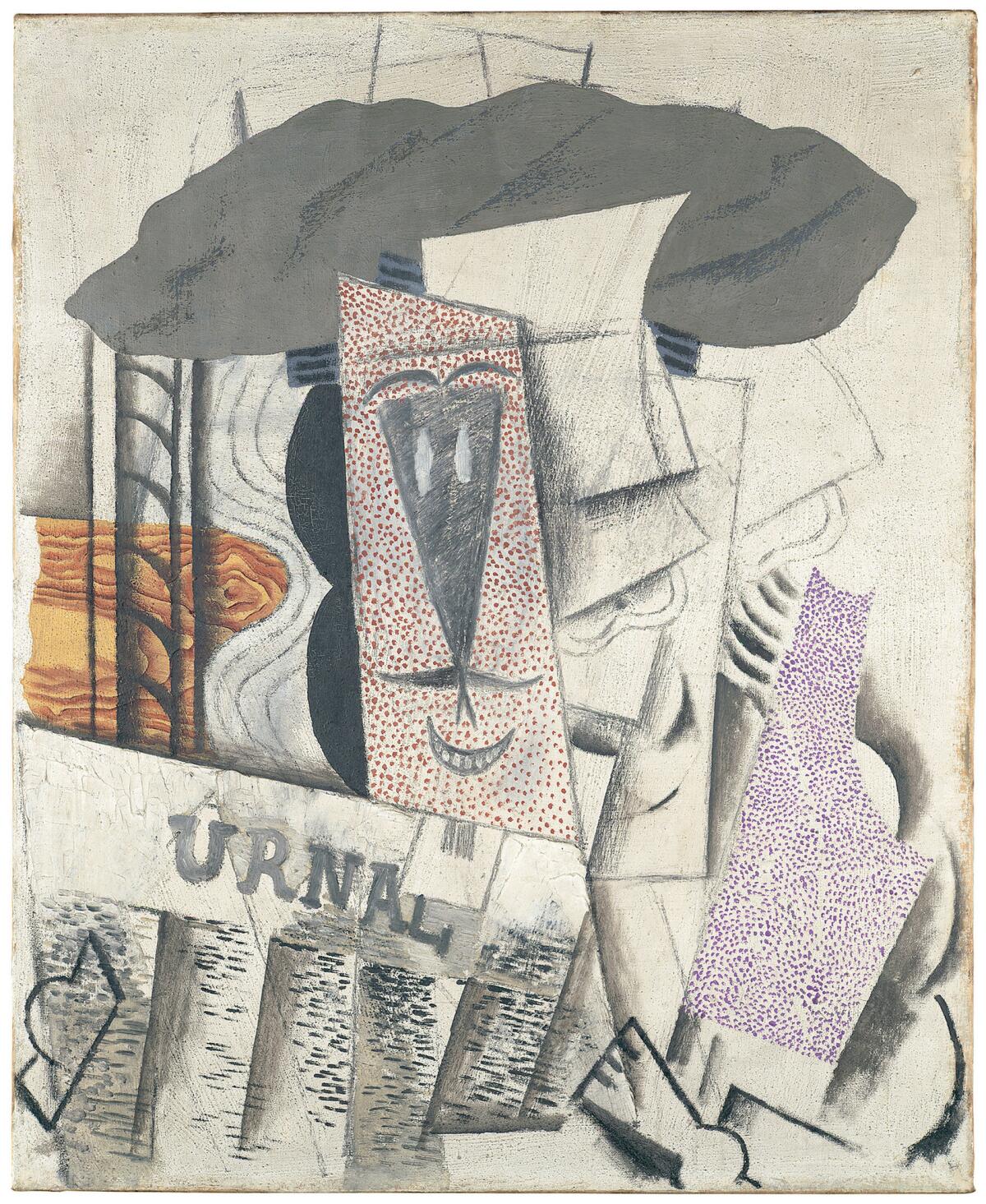

Then comes the essential Cubist room. It’s one of two major highlights in the show, partly because great Cubist paintings are rare in L.A. museum collections.

This selection of 10 includes “Student With Newspaper” (1913-14), its inebriated young man crowned by a jaunty beret, his face derived from a bleary-eyed, West African Wobe mask. Bold block-letters spell “urnal,” a fragment of “journal,” also wittily evoking “urinal.” Mixed materials of plaster, sand, crayon and paint — a delirious experiment — connect it to Rivera’s still life.

Rivera’s magnificent “Zapatista Landscape” will join the show in February, following a prior commitment to a Paris exhibition. (LACMA’s exhibition remains through May 7.) It’s an astounding mountain of Cubist structure cobbled together from the revolution-minded iconography of a serape, sombrero, straw mats and peasant gourds all anchored by the vertical slash of Emiliano Zapata’s rifle.

The catalog, however, is determined to emphasize the painting’s formal properties at the expense of its meanings. Rivera is said to have been furious that Picasso “stole” a new foliage technique from “Zapatista Landscape” for use in the shrubbery in one of his own paintings — shrubbery he later painted out.

I suspect, though, that draining the political power of Rivera’s motif for simple decorative ends might have had something to do with the Mexican’s anger toward the Spaniard. The Zapatistas were hell-bent on agrarian reforms, fueling the revolution. Rivera’s landscape foliage wasn’t just any shrubbery, and Picasso’s “theft” could easily be seen as an affront to a painting that stood as a resolute repudiation of Spanish colonialism.

The catalog even mistakenly says that Picasso’s discovery of his own “native” antiquity, shown by his use of forms from the art of ancient Iberia, predates his Cubist phase, while Rivera’s use of pre-Columbian motifs occurred afterward, beginning in 1921. The claim is disproved by the unmentioned skull in Rivera’s Cubist still life.

In the 1920s, after World War I and the Mexican Revolution were over, what shifted in Picasso’s and Rivera’s work was the artistic balance of power. For Picasso, that meant formal play derived from ancient Iberian sculpture, which reflected his Spanish heritage, mixed with Greco-Roman formats. For Rivera it meant greater prominence for pre-Columbian painting and sculpture.

The show juxtaposes the monumental, tunic-wearing graces of Picasso’s “Three Women at the Spring,” his first Neo-Classical painting, with the “Lansdowne Artemis,” an imposing first-century Roman sculpture of a Greek deity.

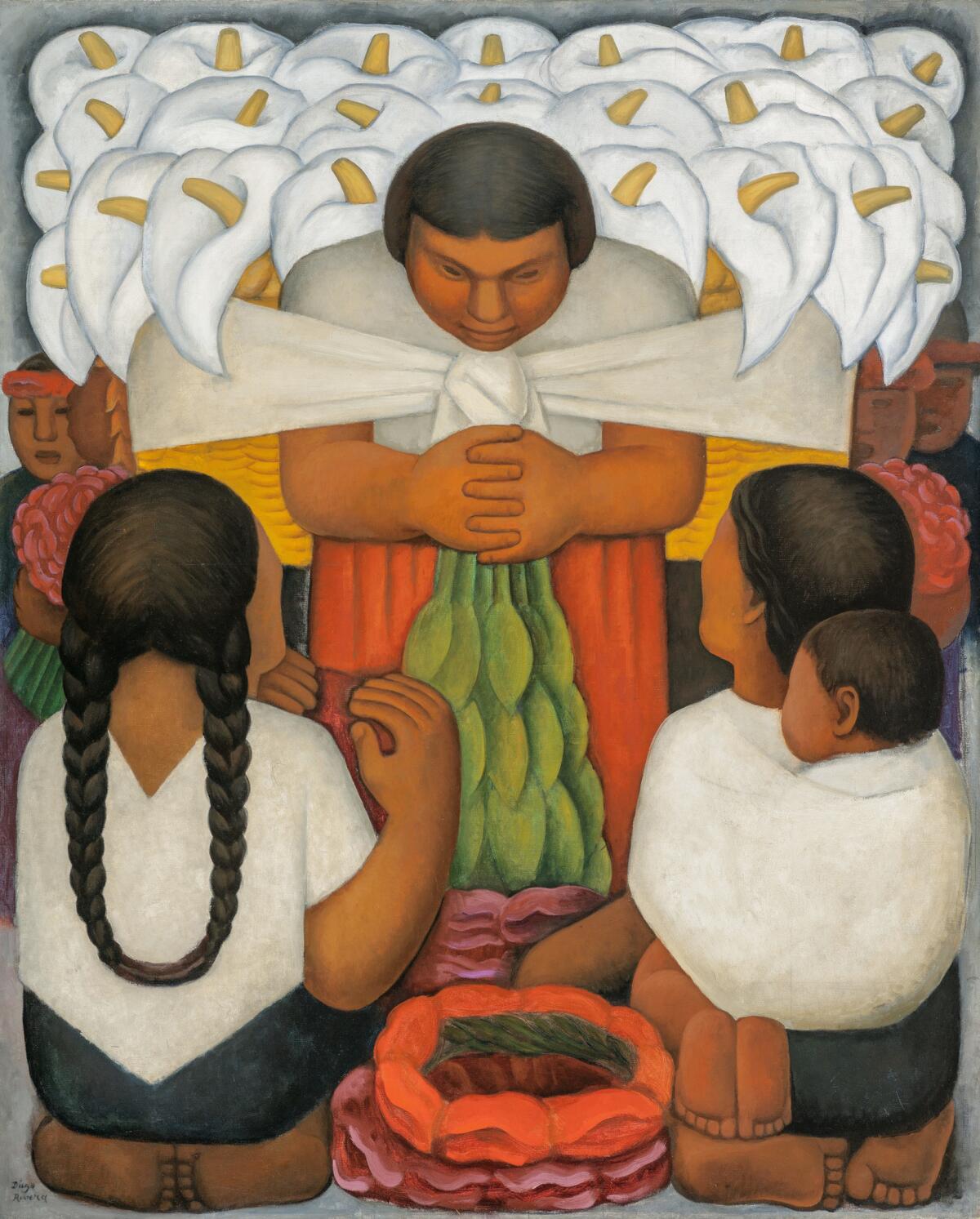

Meanwhile the frontal, bilateral symmetry of Rivera’s “Flower Day,” its central figure wrapped in the red, white and green of the Mexican flag, valorizes the vendor stooping beneath the massive basket-load of calla lilies, their phallic golden stamens transforming the white blossoms into sombreros. The painting faces similarly designed basalt sculptures of the Aztec female water-deity, Chalchiuhtlicue, personification of fertility.

The 15 pre-Columbian sculptures form the show’s other highlight. All but one are on loan from the peerless collections of Mexico City’s National Museum of Anthropology and the Diego Rivera Museum-Anahuacalli, the “modern Aztec temple” housing his mammoth collection of nearly 60,000 ancient artifacts. LACMA deputy director Diana Magaloni, who co-organized the show with director Michael Govan and several specialists, is former director of the Anthropology Museum and arranged the exceedingly rare loans.

In a nutshell, then, the show’s story arc goes like this: The two artists both started with Greco-Roman antiquity, then went Modern; finally, they synthesized the radically new with the venerably old, forming a kind of “Modernist Classicism” — Picasso’s based on European models, Rivera’s on American ones.

After bloody, bitter wars, a destabilized present was undergirded with indigenous foundations. That story is already pretty well-known, of course, so points off for lack of originality. But extra credit for all those impressive highlights.

------------

“Picasso and Rivera: Conversations Across Time”

Where: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 5905 Wilshire Blvd., L.A.

When: Through May 7; closed Wednesdays

Information: (323) 857-6000, www.lacma.org

Twitter: @KnightLAT

ALSO

Thrilling new exhibition shows modern Mexican art is bigger than murals

LACMA’s exhibition on the underappreciated genius of John McLaughlin

Martin Luther broke Europe in two, and Albrecht Dürer painted it back together

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.