Q&A:: Patrisse Cullors on using performance art to confront exhaustion

For the last two years, Black Lives Matter co-founder Patrisse Cullors has been immersed in art, exploring the intersection of performance and activism while earning her MFA from USC’s Roski School of Art and Design.

Cullors, a political organizer who has worked for 20 years to reform the criminal justice system, turned to her exhaustion as a source of inspiration for her April thesis show, “Respite, Reprieve and Healing: An Evening of Cleansing.” This weekend she will perform the work again at Highways Performance Space in Santa Monica.

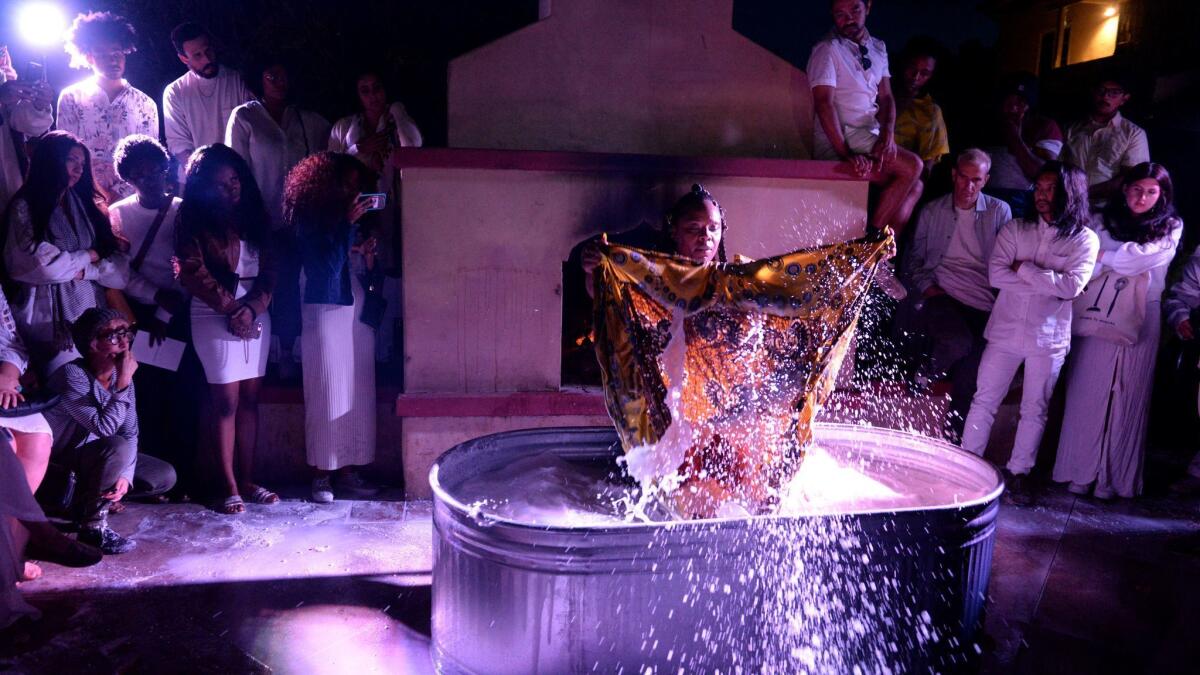

The performance includes two pieces that visually contrast “the history of black bodies being harmed, tortured and brutalized,” she says. In “Hair Wash,” Cullors and a cast of about a dozen black performers wash one another’s hair. In “Weight,” a piece examining the uses and history of salt, Cullors is submerged in a tub filled with 400 pounds of Epsom salt.

Although the USC Roski program had been wracked with turmoil — the entire class of MFA candidates withdrew from the university in protest in 2015 — Cullors says her experience was “really amazing” under its current leadership. She spoke to The Times about her art practice and the significance of the solo show. The interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Many people know your activism but not your art practice. How do you see the role of performance art and social activism?

I trained as a dancer at first. I really moved into the world of performance because I felt like the dance world was too rigid, too bound by the technique of dancing. While I love dancing, I really wanted to work in the fine arts space, the space of experimenting with my body with other objects. For black people in particular, our life is performance. Everything we’re doing has some implication for either ourselves, or the people around us or the systems around us.

This piece in particular that I’m doing really gives me a sense of agency. I get to dictate how the world sees me and what they see me doing, what they hear me saying, or feeling. And oftentimes, we don’t get to make those choices. As black people, choices are made for us, and often it leads to deadly consequences.

This container of art and art practice where you get to curate your audience, you get to curate who shows up, is really powerful for black people. With performance art, while there is a choreography to it, there’s also a bit of the unknown, and black people know that fits really well. We wake up every morning, we do our daily habits. But there’s always an unknown for us, we don’t know what the outcome will be.

There’s a layer of that in the performance art space where you show up to an event, you have an idea of what’s going to happen. Then improv allows you to have more space to figure out what you want to do.

What was your process for creating this work?

It was a two-year process. I spent the last year sitting with objects, like the 100-year-old tub I purchased, sitting with the large horse trough I purchased, just trying to figure out what are these objects saying to me, and what do they want to come to life. I don’t usually sit and say, “OK, this is what’s going to happen.” I usually [say] “this object I want to use,” and then the piece starts appearing to me.

I worked with the curator of this piece, Damon Turner, who’s also the CEO of a company called Trap Heals. He asked me questions about what I wanted to see. Working with him as a curator really helped make this piece into what it is.

Your show is an ode to exhaustion and respite. What are the sources of your exhaustion, and how do you channel that into art?

Many of us are exhausted by the continuous onslaught of violence on our communities. I think black women carry the weight of the world and so our exhaustion looks like something impacted by our own families, but also impacted by the larger systems. I’m exhausted by the pressures of having to make sure this country doesn’t continue to destroy us. It’s exhausting to not just be free and have a sense of freedom.

How I channel that is through my performance practice, or my social practice. Through my organizations I work with, whether it’s Reform L.A. Jails, the ballot initiative that’s going to move the largest dollar amount out of corrections and into mental health, or Black Lives Matter, the global network, supporting chapters across the country who are taking on police brutality in their locales. Or my local nonprofit, the first one that I started called Dignity and Power Now, and stopping the $3.5-billion jail plan in Los Angeles.

I have a lot of sources of hope and support, and I really tap into those places.

How do you find respite when you’re so busy?

I’m a firm believer in therapy. I’m a firm believer of taking the time with family and community, people who love me. I like to have fun. I spend a lot of time laughing. People assume that organizers and activists are just people who are always serious, but people meet me and they think I’m super goofy and funny.

One of your pieces deals with washing black hair. Can you talk about the significance of that routine?

Everybody washes their hair. Everybody bathes. Everybody does these really domestic things. For black people the domestic, as we’ve seen, can also end up leading to our death.

I wanted to also talk about black hair. Black hair is very particular. We are very particular about who touches our hair, what we put in our hair. I thought it would be a very beautiful piece to take the black people mundane and bring it to public. This piece is really an ode to what it looks like to watch black people take care of themselves and take care of each other.

You ask people attending the performance to wear white. Why is that?

It’s a practice I’ve been doing for almost 15 years. When I asked people to come to ceremony, when I ask people to come to ritual, I ask them to wear white. It’s an ode, a nod to my Orisha tradition. This is a space where the audience isn’t just going to come to be a voyeur, you’re going to also be a participant.

What do you want people to take from the show?

I want people to feel a sense of purpose and healing. I want people to be reminded what they care about the most. I want people to walk in the door and let go of all their stressors, all their worries, and just be present for the night.

You recently did a performance piece dedicated to Nipsey Hussle. Where else do you see your art practice going?

I would really love to keep practicing here in L.A. in the gallery space, and I really love public art and being outside the gallery. I want to collaborate with artists like Rafa Esparza. I want to collaborate with other performance artists in L.A. There’s a really amazing performance scene right now.

======

‘Respite, Reprieve and Healing: An Evening of Cleansing’

When: 8:30 p.m. Friday-Saturday

Tickets: $15- $20

Where: Highways Performance Space, 1651 18th St., Santa Monica

Info: highwaysperformance.org

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.