L.A. Opera and Joffrey Ballet give the Orpheus myth some new moves and a different ending

Opera singer Lisette Oropesa is having some trouble with the laces on her pale pink pointe shoes.

It’s a rainy Friday morning, and inside a big, fluorescent-lighted Los Angeles Opera rehearsal space at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, a bevy of ballet dancers in leotards and tights is busy warming up. One young man holds an extended down-dog pose before doing a quick set of push-ups, while another dancer stretches his legs against a ballet bar in front of a wall of movable mirrors.

Two ballerinas gather around Oropesa to help her with those shoes. “If you tie it like this, it’ll stay,” one says, securing the wide pink satin ribbon around the soprano’s ankle. The singer smiles at the dancers with gratitude as she jumps up to take her place in the center of the room.

Oropesa and her two singing costars, tenor Maxim Mironov and soprano Liv Redpath, are vastly outnumbered onstage by dancers from the Joffrey Ballet.

This new production of Gluck’s “Orpheus and Eurydice” is designed, choreographed and directed by the renowned John Neumeier. After its world premiere last fall by Chicago Lyric Opera, Chicago Tribune classical music critic John von Rhein described the production as “an inspired intertwining of ballet and opera” and “an achingly beautiful dream of a show.”

Glimmers of that aching beauty are visible even in a hectic, costume-less rehearsal. L.A. Opera Music Director James Conlon cues the piano and the dancers leap to their places, but after just a few bars of music, Neumeier apologetically calls time out. He needs to adjust one dancer’s arms slightly and reposition another. The music and dancing resume. And once again, Neumeier pauses the action, this time to confer quietly with the tenor about making a slight change to his entrance.

The frequent stopping and starting, the meticulous attention to detail — this is all part of Neumeier’s directorial process, which, he says, takes into account each dancer’s or singer’s individual physicality and skill.

“I watch them,” he says. “I watch what they can do and what they might not be able to do and try to build out of that characters and emotions. I explain to them what they should do, watch how they do it, and then I get the idea of what could be better for them.

“I am the person that will pull apart anything I’ve done and try to find a better way, if there is one.”

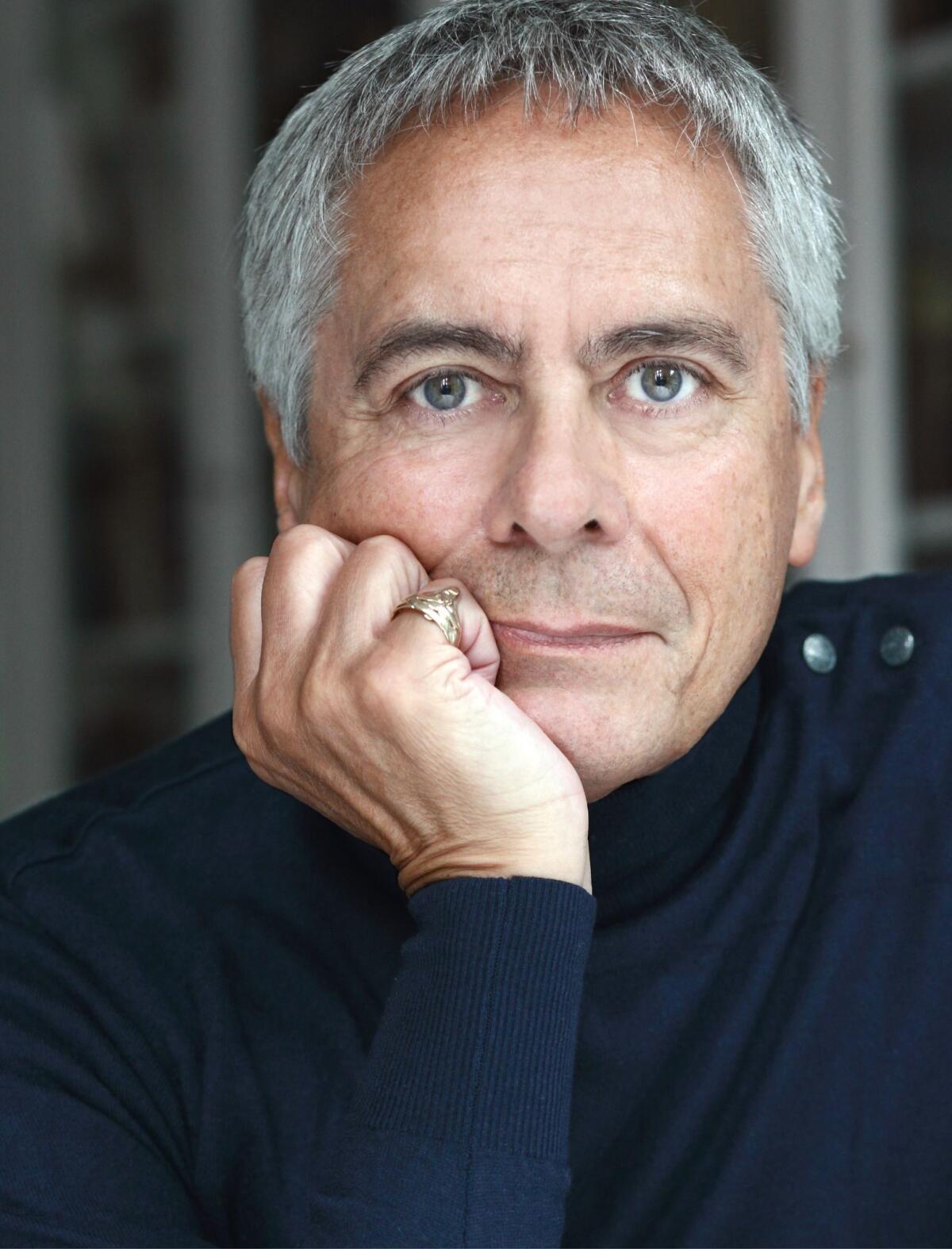

Neumeier performed as a dancer well into his 60s. At 79, in a gray hoodie and black Nikes, he’s soft-spoken and has a gentle but exacting demeanor. Sitting in L.A. Opera General Director Placido Domingo’s empty office before rehearsals, Neumeier is distracted by the cold gray drizzle outside the window. “Where am I again?” he says with a laugh, noting that it was snowing the day before when he left his home in Hamburg, Germany. “I thought I was in L.A. now.”

Neumeier is an American, born in Milwaukee, but he has lived abroad for most of his adult life. This year marks his 45th year living and working in Hamburg, where he is the director and chief choreographer of the Hamburg Ballet. He describes his home in Germany as “a museum of dance” and says he has surely the greatest private collection of historical dance ephemera and materials related to his lifelong muse, the great early 20th-century dancer and choreographer Vaslav Nijinsky.

As a boy growing up in Milwaukee, Neumeier was torn between visual art and dance. Although dance won out, he still enjoys instances when his work requires him to draw, like when he created the sketches for the “Orpheus and Eurydice" costumes and sets. He also says that for him, choreography is “basically painting with the human body in time and space.”

Neumeier was drawn to working on this “Orpheus and Eurydice” in part because of its all-encompassing interdisciplinary form.

“I was drawn to it as Gesamtkunstwerk, the idea that music, text, dance and scenery all come together to say something," he says. “That’s very interesting to me, especially because in this production it is choreographed, directed and designed by the same person. It gives it artistic unity.”

The choreographer’s fingerprints touch every element of the work. He has, in a sense, even inserted himself into the story, which updates the classic myth by transforming Orpheus into a choreographer and Eurydice into a prima donna. In the opera’s first scene, the two lovers quarrel and Eurydice storms out of a dance rehearsal in her pointe shoes only to die moments later in a tragic accident. From there the original myth is followed relatively closely: Orpheus descends into madness and eventually into Hades in an attempt to bring back his lost love.

Love and loss — those are the universally recognizable emotions at the heart of Gluck’s opera, which in this production is sung in its 1774 French version. Communicating those emotions clearly and intensely through movement is Neumeier’s focus. No adjustment of a dancer’s head tilt is frivolous.

“We don’t make movements and steps and then decide to put an emotion on top of them as if we would bake a cake and put frosting on it,” he says. “To all my work, there is an emotional base that is essential to the structure of the choreography. Emotional truth is the foundation of every movement. If they are right, they are inseparable.”

Much of that emotional depth is mined from Neumeier’s own life experiences, although he says nothing in the show is explicitly biographical.

“I do think that anyone who has come through the AIDS crisis stands much closer to death and the feeling of loss,” he says. “And as you become older, there are more people that were very special and dear to you that you do lose, so that experience is certainly one that I know.”

It’s an experience that most everyone in the audience will know, which is why Neumeier is so intent on getting each emotionally charged movement exactly right.

“Truth and honesty of emotion being portrayed in the most direct way, that’s what drew me to this work,” he says. “It speaks very directly of human emotions that all people recognize to some degree. Perhaps we don’t go mad. Perhaps we aren’t tempted to descend into Hades. But certainly we recognize the emotions behind Orpheus’ actions.”

In Gluck’s opera, Eurydice is rescued from Hades. In Neumeier’s version (spoiler alert), she does not come back to life in the literal sense. Instead, she is resurrected through Orpheus’ choreography.

“In the end, she is alive in his artistry,” Neumeier says. “If you are an artist, the person who dies can have an eternal life if you use them as an inspiration for your work.”

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

'Orpheus and Eurydice’

Where: Los Angeles Opera, Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, 135. S. Grand Ave., L.A.

When: 7:30 p.m. Saturday and March 15, 2 p.m. March 18, 7:30 p.m. March 21 and 24, 2 p.m. March 25

Tickets: $16-$324 (subject to change)

Information: (213) 972-8001, www.laopera.org/orpheus

Running time: 2 hours, 30 minutes (with one intermission)

See all of our latest articles at latimes.com/arts.

MORE ARTS:

In Mexico City, a famed orchestra is no match for Dudamel’s 160 student musicians

Is this Andrew Lloyd Webber 'Unmasked' in a new memoir? Mmm, not quite

Artist Olafur Eliasson built a 'Reality projector' of smashing beauty

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.