LACMA gets gravity-defying John Lautner-designed home featured in ‘The Big Lebowski’

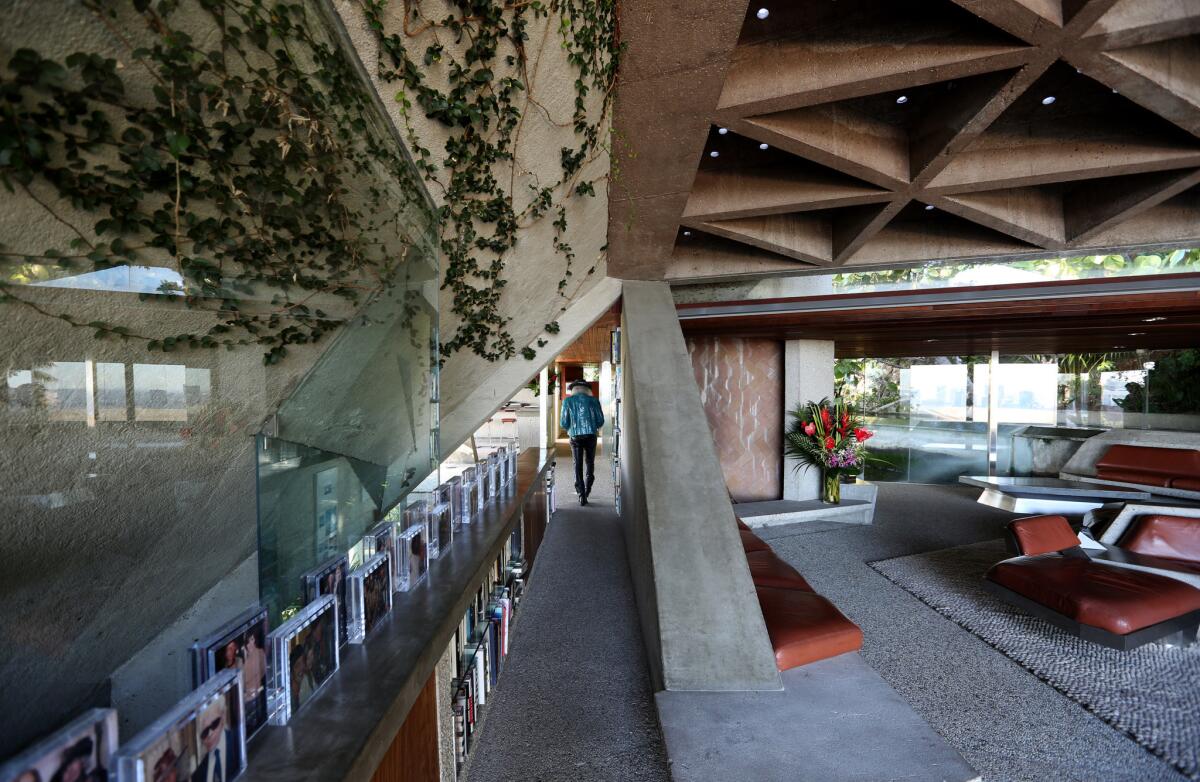

Inside of homeowner Jim Goldstein’s John Lautner house in Beverly Crest.

The architect John Lautner — Frank Lloyd Wright disciple, iconoclast and reluctant Angeleno — produced a number of strikingly unorthodox, gravity-defying houses in the decades after World War II. For pure drama, few can match the 1963 Sheats-Goldstein house just above Beverly Hills.

The living room, familiar to fans of the 1998 Coen brothers film “The Big Lebowski,” where it belonged to a pornographer and loan shark played by Ben Gazzara, begins dark and cave-like, tucked under a coffered concrete roof. Then, as you move out toward the pool, the roof shoots skyward like an ascending airplane wing, bringing you face to face with a view that puts much of Los Angeles at your feet.

Homeowner Jim Goldstein at his John Lautner house in Beverly Crest.

Now the house is poised to meet a much wider audience. James F. Goldstein, who bought the property in 1972 and has made improving and expanding it an expensive personal crusade, has agreed to donate it to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

See more of Entertainment’s top stories on Facebook >>

The bequest, to be announced at a news conference at the house Wednesday afternoon, includes an endowment of $17 million for a maintenance fund, as well as a so-called skyspace artwork by James Turrell and a building adjacent to the main house holding an office and nightclub. The museum has estimated the total value of the gift at $40 million, though Goldstein called that figure “conservative.”

“For me it ranks as one of the most important houses in all of L.A.,” said Michael Govan, the museum’s director and chief executive. “And as one of the most L.A. houses, because of its connection to the view, that long view toward the ocean.”

PHOTOS: A closer look at architect John Lautner’s work

Goldstein has agreed to let the museum organize limited tours and events while he is living in the house. In the longer term, LACMA envisions opening it for fundraisers, exhibitions and conferences, as well as collaborations with other museums.

Inside of homeowner Jim Goldstein’s John Lautner house in Beverly Crest.

The donation is a coup for Govan but a long-delayed one. Not long after taking over as LACMA’s director in 2006, he announced that he was interested in acquiring one or more landmarks of Los Angeles residential architecture, maintaining them in place and opening them to visitors and scholars.

Though innovative architecture is central to L.A. culture, he explained, many of the most important examples are houses tucked away in the private realm and inaccessible to public view. He named designs by Wright, Frank Gehry and the pioneering modernists R.M. Schindler and Richard Neutra.

The plan hit a few snags. Several owners of important houses asked Govan whether the museum wanted to buy their houses, but that’s not what he had in mind. He was looking for a donation — and the promise of an endowment.

PHOTOS: The architecture of John Lautner

In Goldstein, a Wisconsin native who is equally obsessed with architecture, basketball and high fashion, Govan finally found the right donor.

“I want the house to be an educational tool for young architects, and I want to inspire good architecture for Los Angeles,” said Goldstein, a wealthy real estate investor who has been a reliable courtside presence at Lakers and Clippers games for decades, typically wearing outfits by Galliano or Versace, his long white hair tucked under a snakeskin hat of his own design.

The entryway of homeowner Jim Goldstein’s John Lautner house in Beverly Crest.

Goldstein first visited the house — built for Helen Sheats, an artist, and her husband, Paul, a professor — in 1972. Goldstein had been living in a high-rise apartment in West Hollywood but decided that his Afghan hound, Natasha, needed more room.

The property was already in escrow. But when the buyer tried to renegotiate at the last minute, Goldstein stepped in, agreeing to pay the full asking price: $185,000.

These days the house is something of a shrine to Goldstein’s travels, basketball fandom and minor celebrity. The living room is lined with photographs of him posing with NBA players, musicians, models and movie stars. Leading a tour on a recent afternoon, Goldstein casually mentioned that he had hosted a birthday party for the singer Rihanna at the house a few nights before.

Goldstein declined to provide his age. In 2013, he told an interviewer that after attending Stanford he moved to Los Angeles “in the early ‘60s,” which means he is likely in his mid- to late 70s.

The house that Goldstein bought in 1972 hardly represented a pure version of Lautner’s architecture. The living room had thick shag carpeting. The master bedroom was painted turquoise. The driveway was lined with chain-link fencing.

“The house was built originally with a very tight budget,” Goldstein said. “With the exception of the living room, the house contained no concrete and was built with plaster and Formica.”

By 1979, Goldstein said, he’d put aside enough money to take on the job of transforming the house and the hillside. He asked Lautner, whose other well-known houses include the spaceship-like Chemosphere overlooking the San Fernando Valley and a house for Bob Hope in Palm Springs, to oversee the work.

The kitchen and dining area of homeowner Jim Goldstein’s John Lautner house in Beverly Crest.

Together they set about substantially remaking the house. They replaced the original windows, which were separated with steel mullions, with giant sheets of interrupted glass. Ignoring Lautner’s recommendation of a spare landscape dotted with pine trees, Goldstein planted a lush tropical garden, which over the years has nearly enveloped the house. He asked the architect to design built-in concrete furniture for the living room.

“It was never my goal to bring the house back to where it was originally, because it wasn’t perfect originally,” Goldstein said. “My goal was to make it perfect.”

Over time, Goldstein bought several properties bordering his; he now owns five contiguous parcels covering 4 acres, all of which are included in the LACMA gift.

After Lautner’s death in 1994, Goldstein began working with one the architect’s protégés, Duncan Nicholson, to add a large structure topped with a tennis court. The three-level building now includes a nightclub with walls of concrete and glass and offices for Goldstein and his staff.

A screening room is also in the works. The Turrell skyspace, an open-air structure set into the hill below the house and titled “Above Horizon,” was added in 2005.

“From the time I started that project continuing up until now and into the future, there has been construction going on every day,” Goldstein said.

The intensity of that work — as a result of which what was once the Sheats House is now widely known as the Sheats-Goldstein House — complicates the LACMA acquisition. For the most part, the important local examples of modern residential architecture that have been preserved as house museums, such as the Eames House in the Pacific Palisades or the Schindler House on Kings Road in West Hollywood, are fixed and unchanging examples of a particular design era.

Goldstein’s house is something different, an example of the modern residence in flux. It is as much a monument to Goldstein’s patronage as Lautner’s architecture; how much say, if any, LACMA will have in updates to the house while he is living is among the trickier questions raised by the gift.

The time it’s taken Govan to add this first modern house to the LACMA collection suggests that we shouldn’t expect a flood of similar donations to follow. The maintenance required for upkeep — along, of course, with the fact that paintings are portable and architecture is not — means that houses, however important, aren’t collected with anything like the zeal of modern and contemporary art. Paintings don’t leak, nor do paintings have neighbors.

Wright’s 1939 Sturges House in Brentwood, on which Lautner worked as construction supervisor, will be offered for sale by Los Angeles Modern Auctions on Sunday. The bidding range is an estimated $2.5 million to $3 million — a fraction of what collectors pay for important modern paintings or for nearby houses without an architectural pedigree.

Though the Beverly Crest house is marked by an unusually sympathetic relationship between architecture and site, Lautner’s disdain for Los Angeles was well known. He stuck around in large part because there was so much work for adventurous architects in postwar Southern California.

“Lautner remarked at his 80th birthday celebration, when asked what he would do to improve Los Angeles, that we would construct a huge concrete boulder, take it up to Mulholland Drive and roll it down the hill,” Goldstein said.

“He also disliked the administration of Los Angeles in terms of their resistance to his ideas. He was antiestablishment in his mentality. And I’m the same way. So we got along quite well.”

Twitter: @HawthorneLAT

MORE:

Research and respect go into restoring a John Lautner guesthouse

How LACMA found its zoot suit -- and set a new auction record

First look inside LACMA’s Rain Room: an indoor storm where you won’t get wet...honest

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.