Review: How good is the King Tut exhibition? An art critic weighs in

Like Barbra Streisand, Elton John and Cher, Tutankhamun, boy king of ancient Egypt, periodically goes on a world tour for what may or may not be a last live performance for the fans.

Or, in Tut’s case, the last dead performance. Tut is all about the tomb, the afterlife and desperate immortality — a fantastically grandiose and convoluted system that would help define Western civilization for the next several thousand years.

He’s back now. “King Tut: Treasures of the Golden Pharaoh” is newly opened at the California Science Center in Exposition Park, where a nearly 10-month run kicks off a multiyear, multi-city tour, mostly in Europe.

Why an art and archaeology exhibition is at a science museum is not exactly clear. Yet, the show is superior to “Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs,” a tacky for-profit entertainment that was at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 2005. This one is also commercially packaged by a global entertainment agency, IMG, but the generally fine material in the exhibition’s main galleries is more coherently displayed.

What killed the boy king at 19 might be a mystery (infection from a broken leg is now the presumed culprit), but there’s nothing cryptic about why this show has turned up. Egypt has a problem: Too much chaos, not enough tourists. Tut is sightseeing’s celebrity pitchman.

Turmoil has been a mainstay in modern Egypt, now run by a brutal military dictatorship. In a 2013 coup, Gen. Abdel Fattah Sisi overthrew Egypt’s first democratically elected president, imprisoned thousands of dissidents and massacred more than 600 men, women and children at a peaceful sit-in near Cairo’s Rabaa al Adawiya mosque. Just over two years ago, 244 passengers and crew were killed in a suspicious charter airplane crash in the Sinai Peninsula.

Tourism has long been a mainstay for the Egyptian economy. Current numbers are barely over half the all-time high in 2010, just before the political uprising, according to figures tracked by the Central Bank of Egypt. Lately the numbers have been inching up, but public perceptions of instability threaten a huge new tourist attraction.

The Grand Egyptian Museum is a massive complex near Giza, about 10 miles outside Cairo. Almost 20 years in the making and, according to some reports, costing about a billion dollars to construct, the project is about a decade overdue.

Tens of thousands of artifacts have been transferred from Cairo’s fabled Egyptian Museum of Antiquities, new staff offices are occupied, and critically important conservation labs are up and running. But the galleries are unfinished — including those for virtually all 5,000 objects found in Tut’s tomb, the project’s chief tourism lure. The museum’s opening has already been postponed a couple of times. A scheduled May debut was recently pushed back perhaps two years, just as the traveling Tut show is to finish up.

At the California Science Center, the exhibition design for these gilded wood sculptures and assorted implements of daily life is overly theatricalized. Apparently, it is impossible to show ancient Egyptian art in an American museum in something other than darkened galleries made eerie by atmospheric blue lighting and pin spots, a New Age soundtrack humming in the background.

The Duat, ancient Egypt’s realm of the dead, was indeed a nighttime underworld, and it was also dark inside Tut’s intact tomb, where the undisturbed artifacts were famously discovered in 1922. But commercial packaging goes for the conventional every time, and this show’s familiar mannered wrapping is no different.

It is, however, much lighter on the visual razzle-dazzle than the tawdry LACMA outing, and that’s a benefit. After an entry gallery where an introductory short subject on pharaonic Egypt is projected onto a 180-degree screen, gold-colored doors open automatically (think crowd control), allowing entry into the first of nine galleries. The show unfolds in about 150 artifacts.

Sparingly deployed digital screens include a useful animation that shows how Tut’s four canopic jars — storage vessels for his liver, stomach, lungs and intestines — were elaborately packed inside a ceremonial chest. Nearby, the handsomely carved alabaster lid of one jar shows Tut’s serene countenance at its most Michael Jackson-like.

The showstopper: a sentinel that guarded Tut’s Ka, or life force. Blank, jet-black eyes are made from imported obsidian, staring out toward eternity.

The objects carry this exhibition, even though few would be described as major works of art. (A number are labeled “First time out of Egypt,” disconcerting when looking at a rather ordinary pair of gloves.)

Most of the showier gold — 21 finely crafted earrings, bracelets, pectorals and other jewelry found wrapped inside the mummy’s bandages — turns up in the final chamber.

Many of the show’s 15 wooden figures of deities are likewise gilded. Yet, the relative modesty of most of the objects is a boon. An almost matter-of-fact quality is suitable for what was then a common funerary process, hardly unique to a 19-year-old king whose brief reign (1336-1326 BC) was rather uneventful.

The show is divided into four sections. Three outline the elaborate funerary process Tut underwent, from preparation for burial and a journey through the underworld to rebirth for eternity. The fourth concerns the tomb’s 1922 discovery.

To prepare, objects of daily life — vessels, storage chests, a chair, a miniature game board, a bed with lion’s paw feet — are gathered for use in the afterlife. Materials are revealing. A simple footrest is made from woods found in sub-Saharan Africa and along the Mediterranean’s east coast, suggesting the spread of Egyptian power and trade. Other wooden objects are gilded to reflect light or wrapped in incised gold sheets, while carved and painted alabaster, a soft and translucent stone that absorbs light in a gentle glow, is common.

Ra, the mythic sun god, was an essential deity. In the precarious balance between life and death, he represented an element of nature hard to miss in the sun-blasted deserts of Egypt. Light’s invocation is key to Egyptian funerary art.

Tut’s father, Akhenaten, was a radical monotheist who had suppressed the cult of Ra. But after his death, his son returned the god to prominence. That may partly explain the magnificent gold funeral mask that is the most famous of all Tut’s artifacts — one not included in this show (the mask no longer leaves the country) but evoked in a later gallery by a 15-inch gold coffinette where the king’s liver was stored as the mummification process was underway.

Next comes the potentially perilous journey of body and soul through the underworld. Egyptian iconography is extremely complex, the means and methods of navigating assorted demons and lakes of fire not for the faint of heart. In tools, weapons and sculptures, Tut is depicted as dominating everything — man, beast, the worlds of nature and society. An image of all-encompassing power helps smooth his way.

Take one of the exhibition’s most arresting works, a gilded ceremonial shield. The elegant relief carving shows Tut as a warrior handily dispatching a pair of ferocious lions. Marvelously animated through a repetition of beastly legs that unfold like a fan, while their two heads twist and roar in opposite directions, the design recalls even older Assyrian bas-reliefs.

The third section celebrates Tut’s successful rebirth. It is introduced by the showstopper: a slightly larger than life-size sentinel that guarded Tut’s Ka, or life force.

The figure’s blank, jet-black eyes are made from imported obsidian, staring out toward eternity, while gilded garments glisten against black skin. The body is muscular and lithe, but his pose — one foot straight ahead of the other in rigid, physically impossible alignment below a strictly upright and frontal torso — creates an authoritative spectacle of resolute, unshakable strength.

This main portion of the show is on the Science Center’s third floor. Down on the first floor is the concluding section, where the heavy hand of the commercial packager is felt in full, tacky force. It tells the story of the tomb’s discovery by British archaeologist Howard Carter.

There isn’t much to see — a small gilded shrine and four pieces of jewelry, one of them the hefty pectoral with five lapis lazuli scarabs famously photographed around the neck of the water boy who alerted Carter to the steps in the sand that led to the ancient burial site. The items are nearly lost amid long walls of timelines about the discovery and Tut’s celebrity aftermath, along with photographic blow-ups and video talking heads.

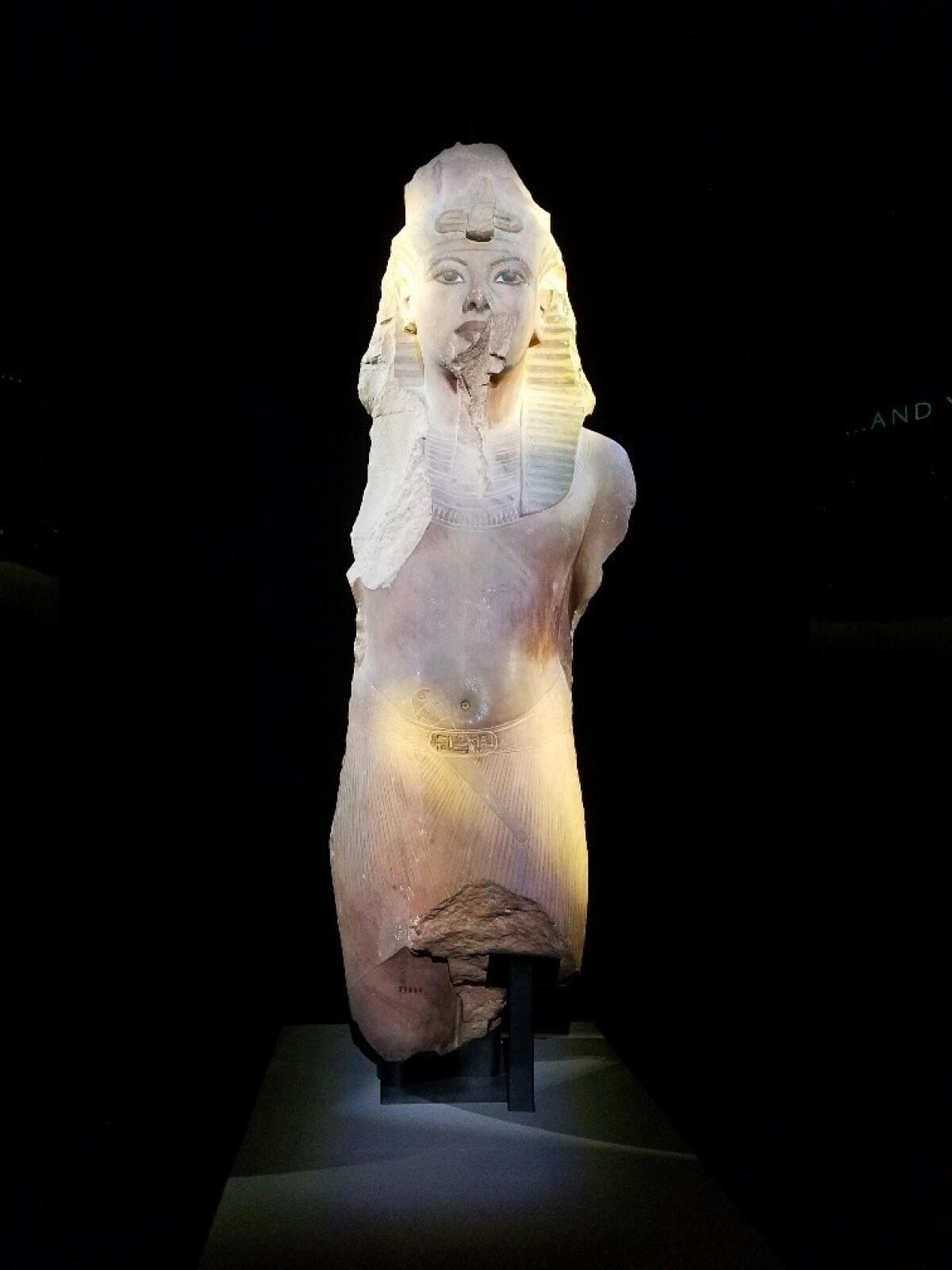

The exit gallery offers up a kitsch crescendo. A fragment of a colossal but mediocre quartzite Tut statue that once stood outside the mortuary chamber is bathed in a pulsing sound-and-light show. A minor work of art, notable mostly for blocky bulk, has been tarted up with flanking digital videos where ghostly specters of the saga’s main players fade in and out over scenes of the vast Egyptian desert.

A drumroll arises, as dappled theatrical lighting brightens into full blaze on the boy king’s face. The digital screens intone that simply speaking Tut’s name will ensure his immortality — a marketing truism faking ancient profundity in an automated performance heavy on the ham and cheese. Time is better spent in the upstairs galleries, where a visitor is not made to feel like a pigeon.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

‘King Tut: Treasures of the Golden Pharaoh’

Where: California Science Center, Exposition Park, 700 State Drive, L.A.

When: Through Jan. 6; open daily

Admission: $19.50-$30

Information: (323) 724-3623, www.californiasciencecenter.org

Twitter: @KnightLAT

ALSO

King Tut: Exhibition may be the last time collection leaves Egypt, organizers say

Getty conservators near completion of work on Tut’s tomb in Egypt

Spring exhibitions that transport to Laguna, Teotihuacan, Iran and beyond

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.