Q&A: Artist Jorge Gutierrez’s ‘Border Bang’ is an ode to the pop culture of his Tijuana youth

When artist and animator Jorge Gutierrez was 9, his family relocated from Mexico City to Tijuana, and he crossed the U.S. border to attend school in San Diego. The process took about two hours daily, as travelers navigated U.S. Customs and the influx of cars inched forward.

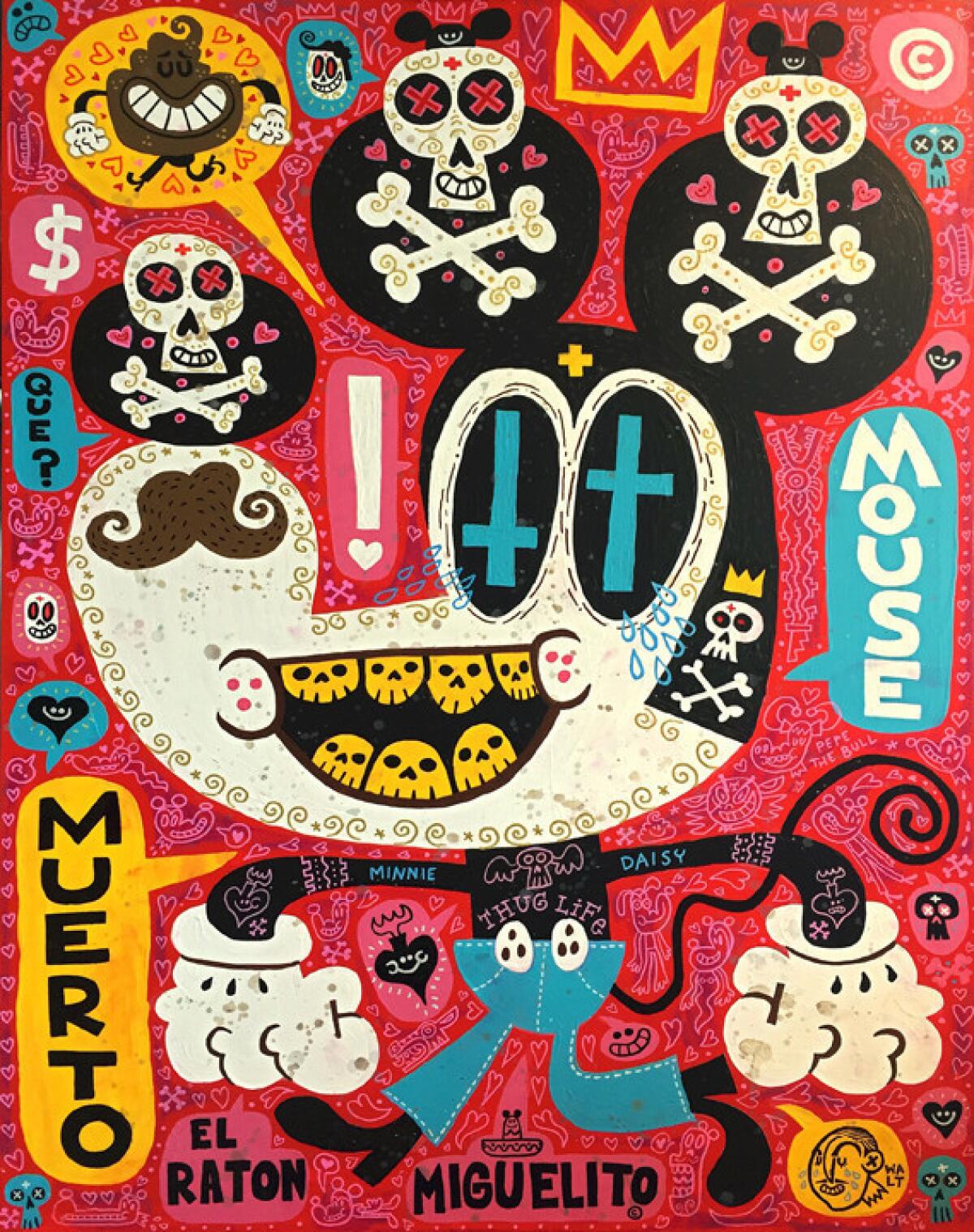

Young Gutierrez occupied himself with the blitz of pop cultural imagery he saw on touristy goods for sale at the border: brightly colored, often bootlegged versions of Mickey Mouse, Godzilla, Elvis and Tupac Shakur on T-shirts, mugs, toys and other items. He fabricated fictional story lines for these curious characters, subversively tweaked versions of globally familiar faces — and they lingered in his subconscious for decades.

Gutierrez went on to study at CalArts and became a successful Hollywood animator, co-writing and directing the 2014 film “The Book of Life,” produced by Guillermo del Toro. But one constant in his life was painting, a hobby he embraced during downtime. His first solo exhibition of paintings, “Border Bang,” will debut at Gregorio Escalante Gallery in Chinatown on Saturday. More than 50 works on canvas make up a dizzying display that’s screaming with color and pulsing with unspoken story; it’s an ode to, and exploration of, the reappropriated cartoon characters and celebrity imagery with which the artist grew up.

“I am the border,” Gutierrez said in a recent interview, “and the border is me.”

What was that experience like crossing the border and being bombarded with this pop cultural onslaught daily? Were they friendly or alienating influences?

As a kid who waited in the border line for hours every morning, it was really overwhelming, exciting and a bit scary all at once. There were bootleg products of all kinds like piñatas, towels, ceramic banks, shirts, wooden toys with characters and people from all branches of popular culture from both sides of the border. You could see Zapata next to Elvis next to Godzilla next to Batman, Magic Johnson, Pancho Villa and Bart Sanchez. I had no idea who a lot of them were, so I would make up stories in my head to justify them hanging out. Plus, new characters would show up randomly or disappear every day. It was a warped window into the world of popular culture on both sides.

What sort of stories did you make up around these characters?

I would see lots of images of Zapata and Pancho Villa next to Spider-Man and Superman, so I assumed all Mexican heroes had to have big sombreros and mustaches. But I knew they had been real people who had fought in the Mexican revolution, so they couldn’t really be superheroes with super powers. I remember I had a Skeletor figure and I had no idea what his story was so, he became my Mexican Dia de los Muertos superhero. Then I watched the He-Man cartoon [in which he’s a villain], and my heart was broken into a million pieces. I still have not recovered.

How is this reappropriated, or bootlegged, pop cultural imagery a reaction to global events? Was there a “border point of view” that affected you as a kid?

The border responds to the dreams, demands and fears of the people who cross, and you see it in what sells. I remember Halloween masks of corrupt presidents of Mexico with devil horns sold really well. The border would comment on things like this, and we were all listening. Currently, they sell El Chapo Halloween masks and Donald Trump piñatas. The border is always current.

You intended to do nine paintings for this show and ended up creating 57. Why?

Once I started, they just exploded out of me. It was as if I was a chef and I couldn’t stop cooking. I had lots of spicy dishes, and I couldn’t wait to share them with everyone. I painted for three or four hours at night while I played movies or music about whatever I was painting. It was very addictive.

When you walk into the gallery, the explosion of color and imagery is exciting but also a bit chaotic, sensory overload. Is this on purpose?

Absolutely on purpose. This assault of the senses, which I feel anytime I walk into a folk art store, is something I try to do with all my work. I want it to feel like a thousand little Mexican cherub angels are kissing you all at once. You like this painting? Well then here’s another 56 for you!

What's your relationship to painting versus animation? Is this show a return to your first love of painting?

In animation, I rarely get to touch paint, and computers are great for making things look perfect, so I spend lots of time trying to make digital work feel handmade. I believe imperfections are what give folk art its unique soul and humanity. Painting allows me to experiment without a net and get real messy. It’s thrilling and scary, and I wouldn’t trade it for anything.

And yes, after working in animation for 16 years, this is a humble return to my true first love of painting. I always say animation is moving paintings with sound and music, so I never really left it completely. But yes, it feels great to return to something that made me so happy as a child.

What visual style were you going for in your paintings? It's a hybrid of your own, which you assert in your concept art for films, and also a riff on Mexican folk and pop art, right?

Mexican folk and popular art is my biggest influence, but I’m also super influenced by all my favorite cartoonists like Sergio Aragones, Quino and Miguel Covarrubias. My two art superheroes are [Pablo] Picasso and [Jean-Michel] Basquiat, who I don’t think people give enough credit to how funny they were. And, of course, I love Loteria cards. One of my paintings is the devil card.

Is the show a love letter of sorts to border commerce and culture? Or, seeing as you are now a successful creator of Hollywood content, is it a critical exploration of bootlegged border imagery?

It is absolutely both. I want the viewer to have my Mexploitation cake and eat it too, and then sell them an unlicensed picture of them eating it on a bootleg T-shirt while I tweet about it. That is “Border Bang.”

------------

“Border Bang,” opens 7-10 p.m. Saturday, ends Aug. 14. Gutierrez will discuss his work at 3 p.m. Sunday. Gregorio Escalante Gallery, 978 Chung King Road, Los Angeles. (323) 697-8727, www.gregorioescalante.com

Follow me on Twitter: @DebVankin

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.