Shakespeare died 401 years ago, but original scripts from his era live on in a new digital archive

One was a roguish figure and possible spy, stabbed to death after a mysterious arrest. Another wrote works of biting and often cynical satire. A third wrote only a few plays before dying in his early 30s, but not after penning some of the finest, and still startling, works of Elizabethan erotica.

Christopher Marlowe, Thomas Middleton and Thomas Nashe — despite the best efforts of high school and college English teachers — remain also-rans compared with

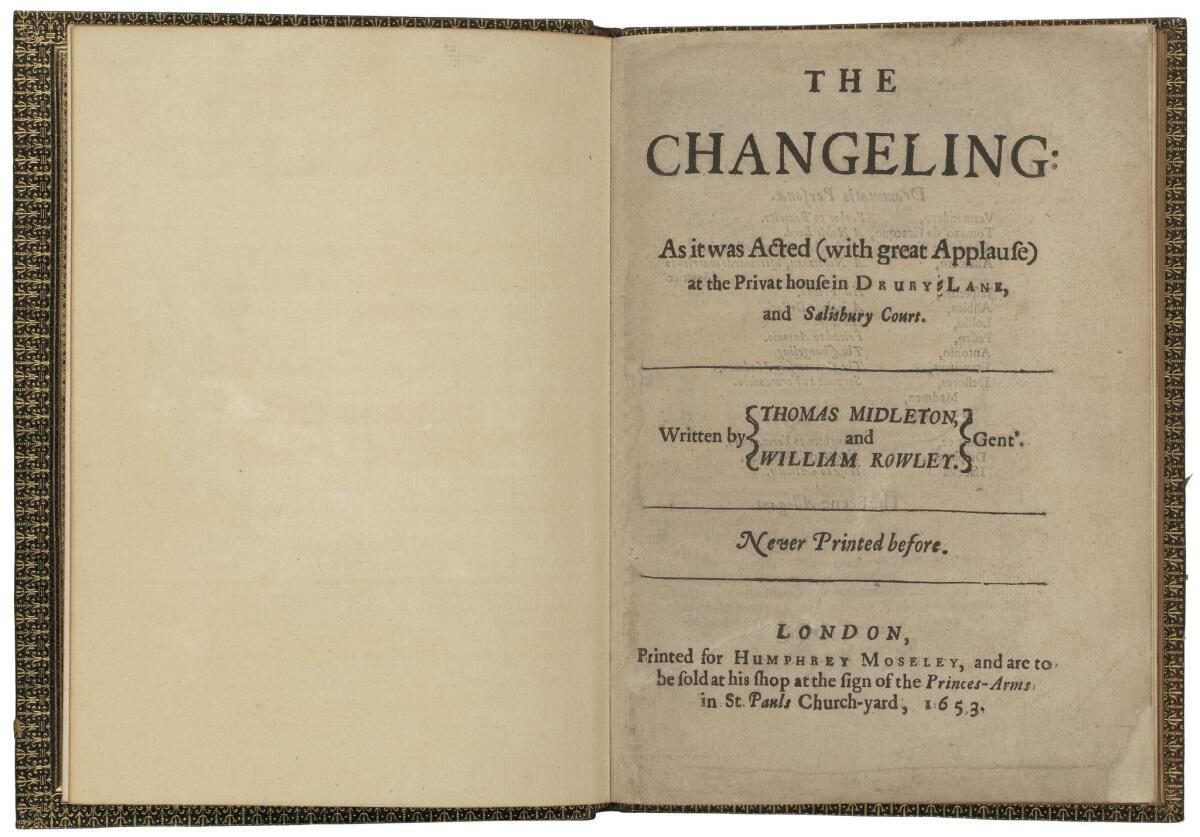

On Sunday, the Folger Shakespeare Library — the august institution based in Washington, D.C., that includes a research institute as well as a celebrated theater — will try again to change this. Last year, on the widely celebrated 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death, the library offered a digital archive of the playwright’s work. This year, on the 401st, the Folger will open a Digital Anthology of Early English Drama, which makes original scripts and visual images from 40 plays available to anyone with Internet access. It’s at emed.folger.edu.

The yoking of 16th century drama to 21st century technology may seem incongruous. But to Mike Witmore, the Berkeley-educated director of the Folger, it’s a natural, almost inevitable pairing.

“If you think about Shakespeare and why we even know who he was, it was because of the first great media revolution,” Witmore says.

He means printing, which came to England in the 1470s, less than a century before the Bard’s birth. Theater, he says, is “an ephemeral art form that disappears the moment it’s created” — unless someone is able to print the script.

“Digital media is the second great wave, and making this material available in digital form is part of our mission.”

To Kathleen Lynch, the executive director of the Folger Institute, playwrights like Marlowe and Nashe are more than just supporting players. She sees the swirl of poets in late Elizabethan and Jacobean London as “this whole vibrant scene, which helps us understand Shakespeare’s world, and that helps us understand Shakespeare.”

And as brilliant as the man from Stratford was, he didn’t come up with everything himself.

“He was also pushed to be better, by some of his colleagues in the theater,” she says.

Marlowe, for instance, who was born the same year as Shakespeare, was the more famous and influential of the two until his death in 1593.

And as with the wealth of blues and folk bands that surrounded the Beatles in 1960s England, other London dramatists did some things better, or more emphatically, than Shakespeare. Urban comedies were rarely part of his oeuvre; most of his happy plays were set in imaginary or abstracted classical settings. “The Roaring Girl” (a piece about a female thief by Middleton and Thomas Dekker), “The Knight of the Burning Pestle” (Francis Beaumont’s meta play that parodies theater-going and chivalric romance) and fully blown revenge tragedies are the kinds of plays the Bard never turned out quite so well.

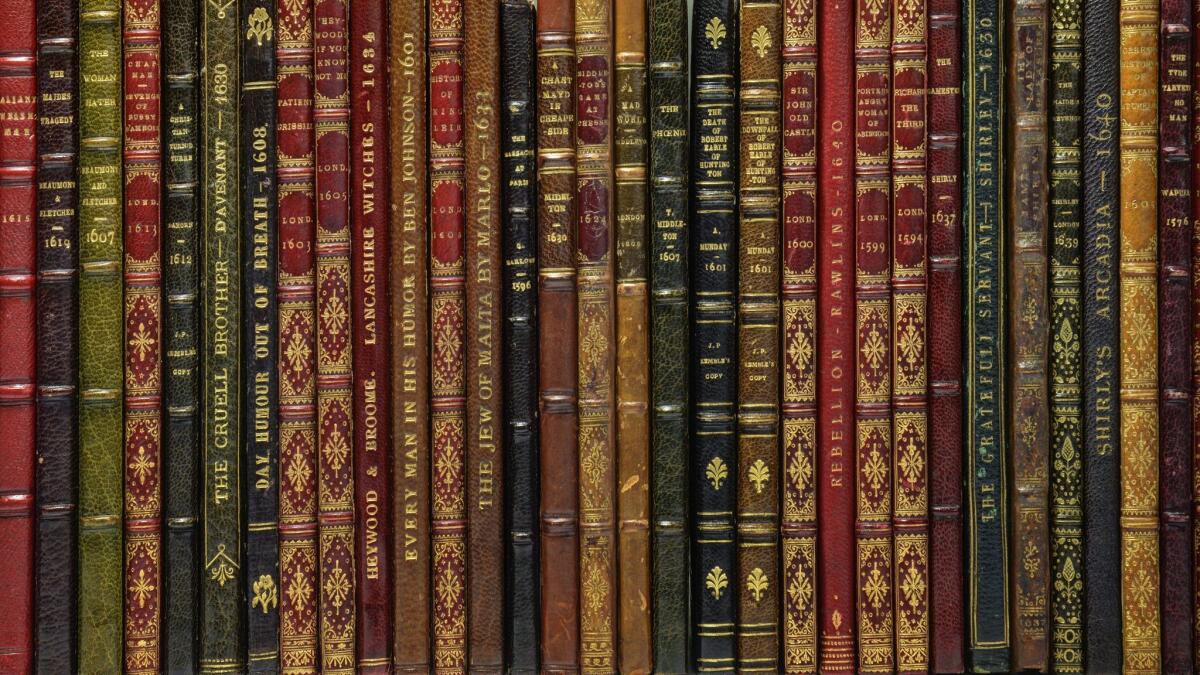

The archive ranges from the 1570s, when London’s first commercial theaters began to open, to the 1640s, when Oliver Cromwell and his Puritans, who also beheaded King Charles I, shut down all of England’s theaters. (Ben Jonson, the era's most influential playwright and poet, is not represented in the archive initially but will be part of a second wave arriving in June.)

The Folger — the largest repository of Shakespeare material in the world — has done innovative work on digital archiving, but it’s not alone, said Miriam Posner, a scholar of the digital humanities at UCLA. The Getty, the New York Public Library (which has well-regarded archives of restaurant menus and stage musicals) and the London-based Wellcome Trust are acknowledged leaders.

In the early days of the Internet, she says, cultural institutions worried that making their wares available online would discourage people from actually visiting them. “But it turned out not to be true — it ends up driving interest and driving attendance,” she says. And work from the early days of printing, when almost every edition was distinct, looks so “weird and unexpected” to contemporary eyes.

Witmore, the Folger’s director, points out that part of what makes Shakespeare and his peers so interesting is that they worked at the beginning of the modern world.

“One of the things he grasped was that the world was changing in serious ways,” he says. But all the writers of the day found themselves at the crux of something new: the birth of real science, the beginnings of religious and free speech, colonial expansion and trade across Europe.

The director hopes the archives give “the full picture of Renaissance professional drama.” As he puts it: “We want it to be available to high school students, English teachers, and enthusiasts who see a play or two a year and want to know more.”

Support coverage of the SoCal arts scene. Share this article.

ALSO

Ibsen's radical 1879 play about women's equality gets a 2017 sequel

Center Theatre Group at 50: An artistic director plots the second act (Hint: Think Hollywood)

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.