Review: MoMA’s love-hate relationship with Frank Lloyd Wright is on display in wide-ranging new retrospective

The relationship between the Museum of Modern Art and Frank Lloyd Wright has been very complicated for a very long time.

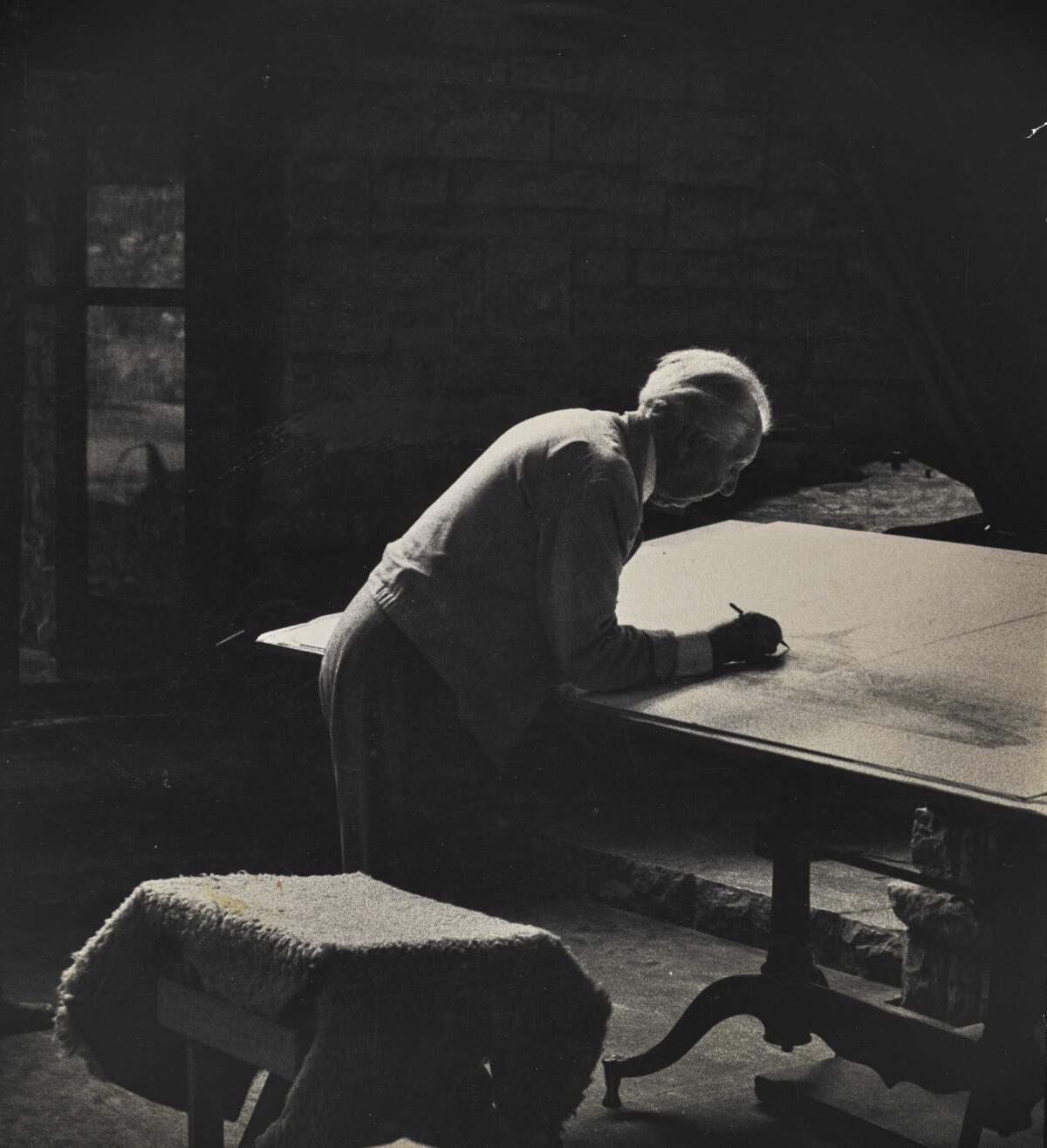

Wright has appeared in more MoMA exhibitions (11 in all) than any other architect. Five years ago the museum and Columbia University jointly acquired his mammoth archive. This summer, to celebrate that acquisition and mark the 150th anniversary of Wright’s birth, the museum has opened a wide-ranging and often surprising exhibition called “Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archive.”

Yet MoMA, as a leading champion of orthodox modernism, has also shared (and sometimes amplified) that movement’s doubts about Wright.

Wright, for his part, both craved attention from the museum and, when it came, wondered if it meant he’d slipped onto the wrong track. MoMA’s favored architecture was for years the unforgivingly spare brand of modernism known as the International Style. Wright’s career-long interest was developing something closer to a National Style, a democratic architecture for America that drew freely and sometimes indiscriminately from premodern and foreign sources (Asian and Latin American as much as European) but might qualify in some fundamental sense as indigenous or homegrown.

Wright died in 1959, at the age of 91, but “Wright at 150” suggests that the museum can’t shake the old ambivalence. Or maybe doesn’t want to. The exhibition treats the arrival of the architect’s archive in New York as — by turns — a gold mine for a new generation of scholars, an inevitability in this milestone year and something of a burden.

Mostly that contradictory attitude is faint enough to be imperceptible, or nearly so. In a couple of places, when the show pointedly makes room for a couple of bracingly modern drawings by the German architect

“Wright at 150,” which fills a suite of third-floor galleries recently redesigned by the New York architects Diller, Scofidio + Renfro, follows an unusual format. Bergdoll, a Columbia architectural historian who directed MoMA’s architecture and design department from 2006 until 2013, is not a Wright expert. (European architects, including Mies, have been the focus of his work.) Nor are most of the 11 co-curators Bergdoll and MoMA’s Jennifer Gray tapped to help them put the show together. Among the best-known Wright scholars, only Princeton’s Neil Levine makes an appearance here.

Bergdoll’s goal was to keep the exhibition from simply restaging the most familiar arguments about Wright. Instead he asked each contributor to choose a single object, drawing or project from the archive to explore.

The approach pays some real dividends. The deep bench of co-curators recruited by Bergdoll has uncovered material charting Wright’s relationship to a range of subjects under-explored until now, particularly landscape, labor and race.

Yet for all the elegance of its presentation and the novelty of its curatorial approach, the exhibition has a dutiful feel. The combination of Wright’s 150th birthday and the arrival of his papers in New York made a major MoMA exhibition essentially inevitable, especially when one considers the crowds it’s bound to attract before its 3 1/2-month run is up.

There are places in the show where Bergdoll’s approach resembles crowdsourcing, a smart attempt to capture the wisdom of a diverse group of architectural historians. There are others when it looks more like outsourcing, an effort to shift the work of reassessing an endlessly analyzed architect from MoMA and Columbia to a group of lesser-known (or maybe more eager or pliable) scholars.

“We were not trying to put together a total Frank Lloyd Wright,” Bergdoll told MoMA director Glenn Lowry during an onstage conversation at the museum. Instead the show is meant “to announce that Frank Lloyd Wright is open to new interpretations” and that “the archive is here and it’s open.”

The picture of Wright the show presents is (essentially by design) fractured, incomplete and inconsistent: a Cubist portrait by committee. Around a central hall containing presentation drawings of some of Wright’s pivotal projects — a concession to the idea that the public will demand to see the Guggenheim, Fallingwater and the rest of the greatest hits — are 12 smaller spaces, each the domain of an individual scholar or pair of curators.

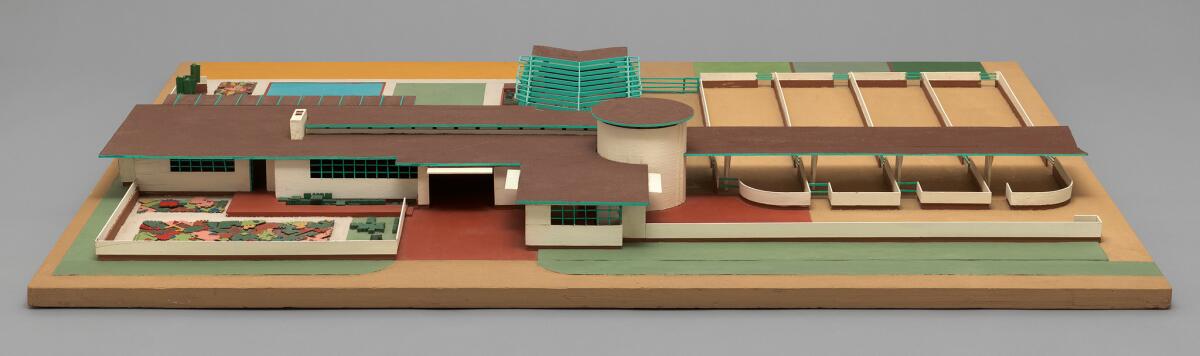

They include the University of Washington’s Ken Oshima on Tokyo’s Imperial Hotel, a commission that helped salvage Wright’s career during a desperately lean period in the 1910s; MoMA’s Juliet Kinchin on an experiment in agriculture, the Little Farms Unit, that Wright pursued during the Depression; Columbia University’s Mabel Wilson on an unbuilt design by Wright for a model school for African American children; and Elizabeth S. Hawley on Wright’s proposal, also unrealized, for the Nakoma Country Club in Madison, Wis.

A section on housing by Matthew Skjonsberg (a Swiss architect who studied at the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture in Arizona) and UCLA’s Michael Osman is largely dedicated to the four concrete-block houses Wright built in Los Angeles and Pasadena in the early 1920s. Each of the four was an idiosyncratic attempt to blend a new system of modular production with flat-roofed Modernism, pre-Columbian ornament, Japanese details and a thoroughgoing exoticism, if not romanticism.

“Wright at 150” comes into sharpest focus when its layout matches its themes and vice versa. The architect had a career-long interest in designing small prototypes that, if produced in multiples, might serve a self-styled nation of individuals: not just the Little Farms (and a related project for a series of town halls) but most famously Wright’s Usonian houses, which he saw (over-optimistically, as it turned out) as a democratic experiment capable of bringing high design to a broad public. At its best what Bergdoll has conjured is a series of Little Shows on America’s most famous architect.

Throughout his career Wright aimed alternately to keep pace with modern architecture and keep his distance from it. What looked to him and his followers like an inventive search for an authentically American architecture looked to acolytes of European modernism more like the trap of nostalgia.

Bergdoll appears to endorse this second point of view in choosing to add a pair of designs by Mies to the one gallery he curated himself, on Wright’s speculative 1956 design for a mile-high skyscraper, the Illinois. One is a 1954 collage by Mies of his design for the Chicago Convention Hall. The other shows the German architect’s well-known 1921 drawing for the Friedrichstrasse skyscraper in Berlin.

If the goal in part is to snap viewers out of whatever Wrightian trance they might have fallen into, staring at one gauzy drawing or watercolor after another, the strategy works all too well. The two images by Mies are like a blast of cold water, a sharp slap of avant-gardism. Anybody who knows how exceptionally well Bergdoll knows Mies’ body of work will also recognize his attempt to signal to fellow modernists that he hasn’t drunk the Wrightian Kool-Aid.

If forced to choose between the two architects I would, like Bergdoll, come down on the side of Mies. But there’s something of the dog whistle in how he deploys those two images.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

‘Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archive’

Where: Museum of Modern Art, New York

When: Through Oct. 1

Info: Moma.org

Twitter: @HawthorneLAT

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.