How did Elliott Hundley curate 7,500 artworks into a 39-piece MOCA show? With scissors

You could say that Elliott Hundley likes to collect things. The painter and multimedia artist is known for densely storied works with a teeming array of materials that he stockpiles in his cluttered downtown L.A. studio — paint, fabric, wood, wire, scores of photograph cutouts and found objects. Not to mention ancient myths and other narratives, which often course through his canvases.

Now, the artist, who has two exhibitions on view in L.A. and was recently awarded a 2019 Guggenheim fellowship, has pivoted. He’s still amassing and juxtaposing objects, a central part of his practice, but most recently, he has applied his approach to 39 works at the Museum of Contemporary Art for an exhibition he co-organized.

As part of MOCA’s 40th anniversary, the museum invited artists to collaborate with its curators on re-installations of the permanent collection. “Open House: Elliott Hundley,” which centers on contemporary collage and assemblage art, kicks off the series. Colombian-born artist Gala Porras-Kim’s take on the collection will open in October.

With more than 7,500 objects to choose from, where does an artist-tuned-curator even start?

With a pair of scissors, Hundley says, shaking his head at the enormity of the project during a recent walkthrough of the exhibition.

Cutting up and stockpiling minuscule images to use in his own art is something Hundley does in his downtime to relax, he says. It’s a calming, meditative, almost performative part of his art-making. He approached the MOCA show in the same way. After combing through three enormous binders listing thumbnail pictures and descriptions of every work in MOCA’s collection, Hundley requested a second set of binders to cut up, carving out each individual artwork and making piles on a tabletop.

“I made a pile of things I didn’t know about, I made a pile of things I loved,” Hundley says. “I made a pile about drawing in space, and a pile about skin. I’m a visual person, so I wanted to see how the works related to one another. For me, it wasn’t as cerebral. It was a very tactile process.”

He and MOCA assistant curator Bryan Barcena whittled down the works before having maquettes made, so they could further play, rearranging the tiny pieces on a model of the museum. The resulting “constellation” of artworks, across three MOCA galleries, represents a sort of three-dimensional assemblage work itself, one that explores approaches to collage in painting, printmaking, photography, sculpture and video as it also draws connections between artists.

“The sensibility that the material process engenders is one of reconciling dissonance,” Hundley says. “They’re all taking materials and images and symbols out of their context and putting them in a new context within a new group of symbols and materials — and the result is that everything gets transformed.”

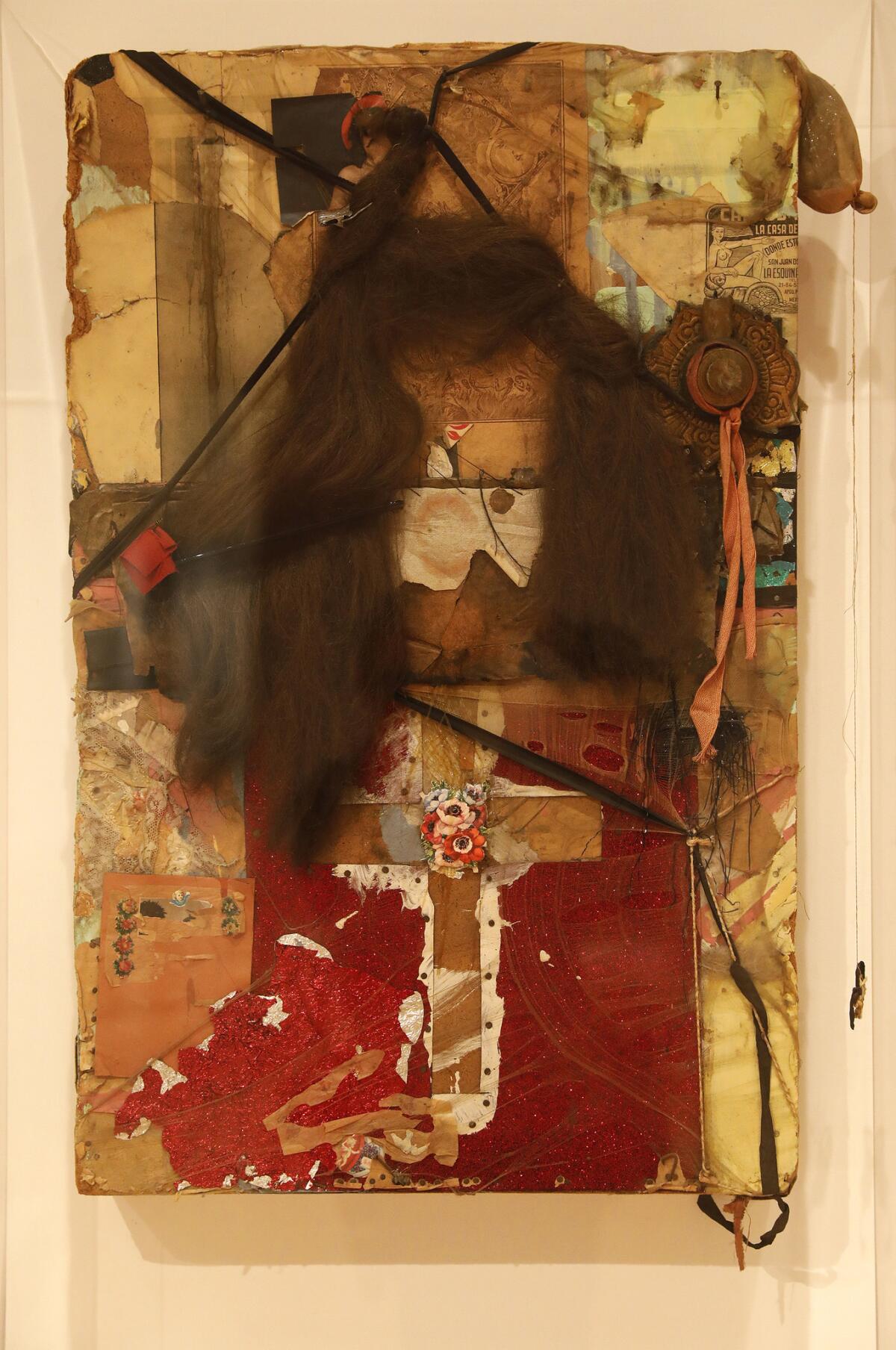

Hundley included one of his all-time favorite works, Bruce Conner’s “Senorita” (1962), which he saw for the first time more than a decade ago on a tour through MOCA’s storage vault when he was in grad school. He included works by influences such as Robert Rauschenberg and Betye Saar, along with his former UCLA professor Lari Pittman. There are discoveries he didn’t know MOCA owned, such as Raymond Saunders’ “Palette” (1983), along with works that had never been displayed at the museum before, like Michel Majerus’ multipanel painting “MoM-Block II” (1996). Hundley included his own ornate banner, the sculptural assemblage “Hyacinth” (2006), which references a Greek myth about love and death.

“I was trying to put things together that maybe don’t belong together, but where one can intuit an underlying logic or shared, maybe, values,” Hundley says.

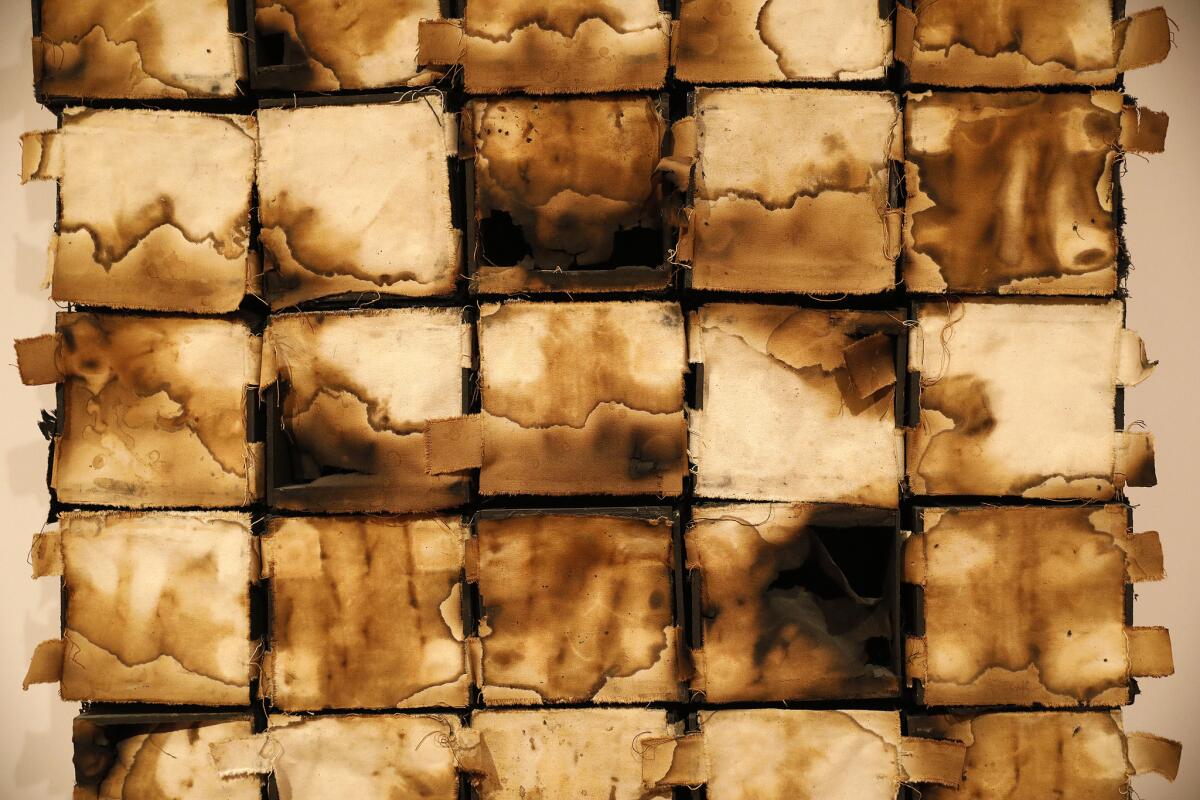

Many of the works, such as Jose M. Fors’ sepia-toned family photo collage “Los Retratos III” (2001) and Leonardo Drew’s grid of burnt, stained canvas blocks, “Untitled” (1994), speak to memory and the passage of time, a through line in much of Hundley’s work. They’re hung near Brenna Youngblood’s equally distressed “3 dollar bill (dirty money)” (2013).

“The distressed surfaces, these are things — images and materials — that have been resuscitated and repurposed,” Hundley says.

Spending more than a year immersed in MOCA’s catalogs sparked a renewed appreciation for the depth of the museum’s holdings, Hundley says, but he also noticed voids in the collection.

“I saw that there were gaps in the representation of some local, very important artists,” he says, adding that two of the works in the show are on loan: Saar’s assemblage “The Destiny of Latitude & Longitude” (2010) and Noah Purifoy’s “One White Paint Brush and a Pony Tail” (1989).

“MOCA does own a Betye Saar, but it’s a small work, and I think she’s a master of assemblage and was central to the idea for the show,” Hundley says of why he borrowed a more significant work from the artist. “And Noah Purifoy, it’s the first piece you see when you walk in the show. Again, he’s a local who’s a master in this way of working.”

As Hundley was organizing the MOCA show, he was making work for an exhibition now on view at Regen Projects gallery. The enormous abstract, sculptural landscapes in “Clearing” are partly influenced by Hundley’s MOCA experience.

Barbara T. Smith’s wall assemblage “Blue Shards” (1997-99), for example, inspired Hundley to collect materials for his canvases as she did, stumbling upon discarded objects while on long, meditative walks, as opposed to scouring thrift stores or dumpster-diving.

“No one would know that; it’s not a part of the meaning of the work,” Hundley says. “It’s just a part of the process of me trying to learn about her, and in learning about her and her method, grow myself as an artist.”

The five new works in “Clearing” are explosions of color and texture that are dizzying up close and form loose, disjointed landscapes from afar. Some of the artists featured in “Open House,” such as Rauschenberg, are represented in the collaged canvases, but the two shows are not meant to be in dialogue — in fact, the opposite. The Regen works are devoid of any sort of imposed narrative.

“I’ve had so many exhibitions, one after another, about works of literature and drama, and I felt the need to make a physical and material advance,” Hundley says. “And to do that, I didn’t want to be tethered to predetermined content.”

MOCA: New shows and future free admission are signs of the museum’s resurgence, our critic says »

The show is a “clearing” on many levels, Hundley says. “Clearing” refers to using 20 years’ worth of materials in the new works. It’s a meditative clearing of the mind, and the landscapes allude to a physical, spatial clearing.

“It’s about taking stock of the past to create a foundation to move forward,” Hundley says.

MOCA’s “Open House” series might do the same for the museum, he adds.

“The more artists become really knowledgeable about the collection, the more it will be seen in the community as an archive and resource for study, not just for display,” he says. “And having artists with their hands in it may also help them point out ways to tell the kind of story they feel is representative of our communities.”

=====

Elliott Hundley

“Open House”: Museum of Contemporary Art, MOCA, 250 S. Grand Ave., L.A. Through Sept. 16; $8-$15. (213) 626-6222. moca.org

“Clearing”: Regen Projects, 6750 Santa Monica Blvd., L.A. Through June 22. Free. (310) 276-5424. regenprojects.com

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.