Review: In ‘Elliot, A Soldier’s Fugue,’ the silent pain of war echoes through three generations

February is Quiara Alegría Hudes month in Los Angeles. For the first time, the three plays in her heralded Elliot trilogy will be performed concurrently at separate theaters in the same metropolitan area. It’s taken a while for the series to reach our shores, but the L.A. theater community, led by Center Theatre Group, is giving Hudes the royal treatment she deserves.

“Elliot, A Soldier’s Fugue,” the 2006 drama that began the series, opened Saturday at the Kirk Douglas Theatre. “Water by the Spoonful,” the Pulitzer Prize-winning middle drama, opens Sunday at the Mark Taper Forum. And “The Happiest Song Plays Last,” the final installment, opens later this month at the Los Angeles Theatre Center.

The plays share characters and thematic concerns, but each is a standalone experience with its own dramatic architecture, theatrical tempo and emotional palette. You don’t have to see them all, but why would you pass up an opportunity to become acquainted with one of the leading voices of this thrilling new generation of American playwrights?

INTERVIEW: Quiara Alegría Hudes on finding drama in family history »

Hudes, who studied music at Yale as an undergraduate before getting a master’s in playwriting at Brown, has developed unique musical structures for each play in the trilogy. Her body of work, which includes the book for the Tony-winning musical “In the Heights,” translates social justice concerns into dramatic scores.

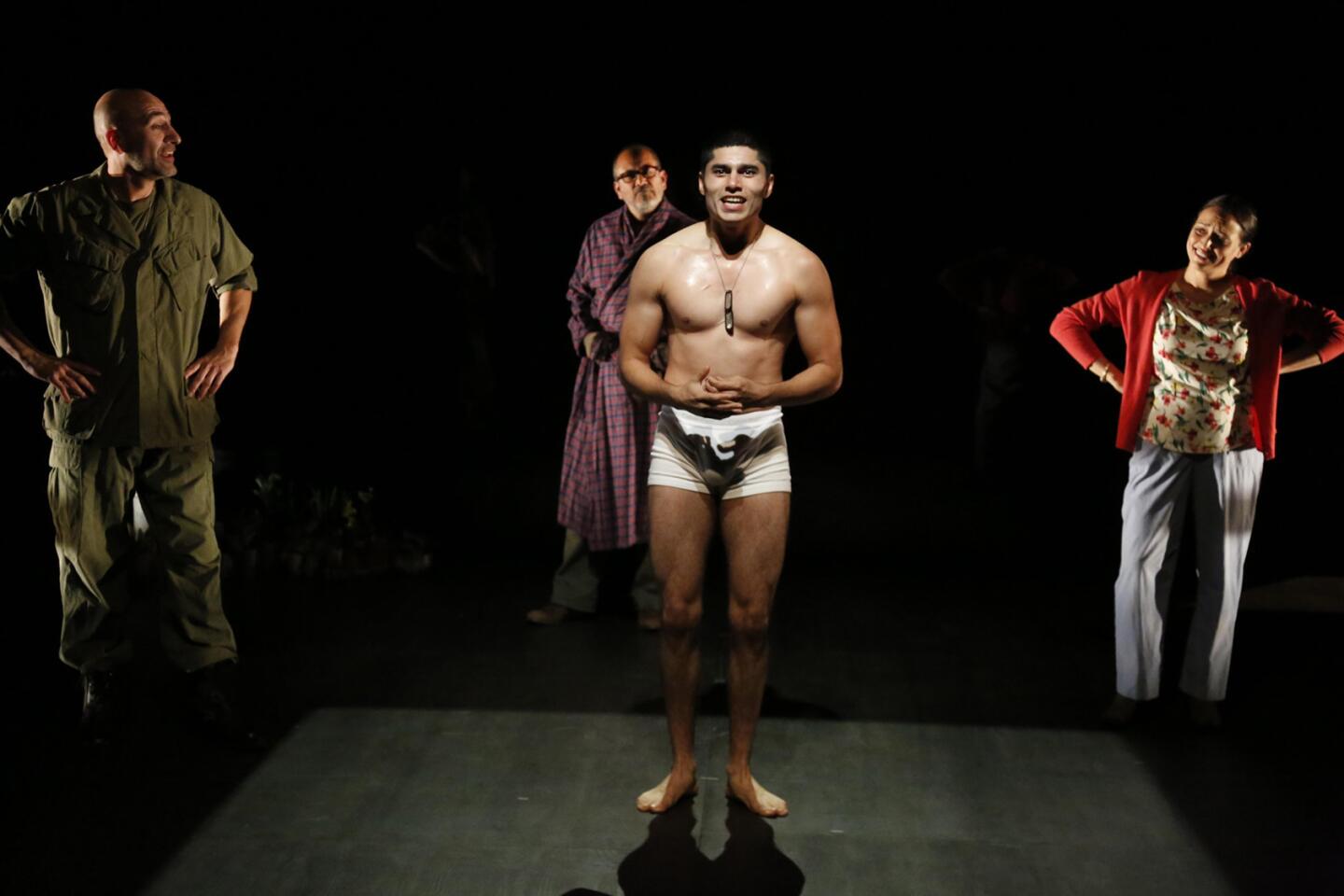

“Elliot,” which looks at the experience of three generations of military veterans in a Puerto Rican family, centers on Elliot (Peter Mendoza), a North Philadelphia native and recent high school gradate who’s about to ship off to Iraq with the Marines in 2003. His story is interwoven with his father’s Vietnam War past and his grandfather’s Korean War history in a drama that organizes itself along the mingling lines of a fugue.

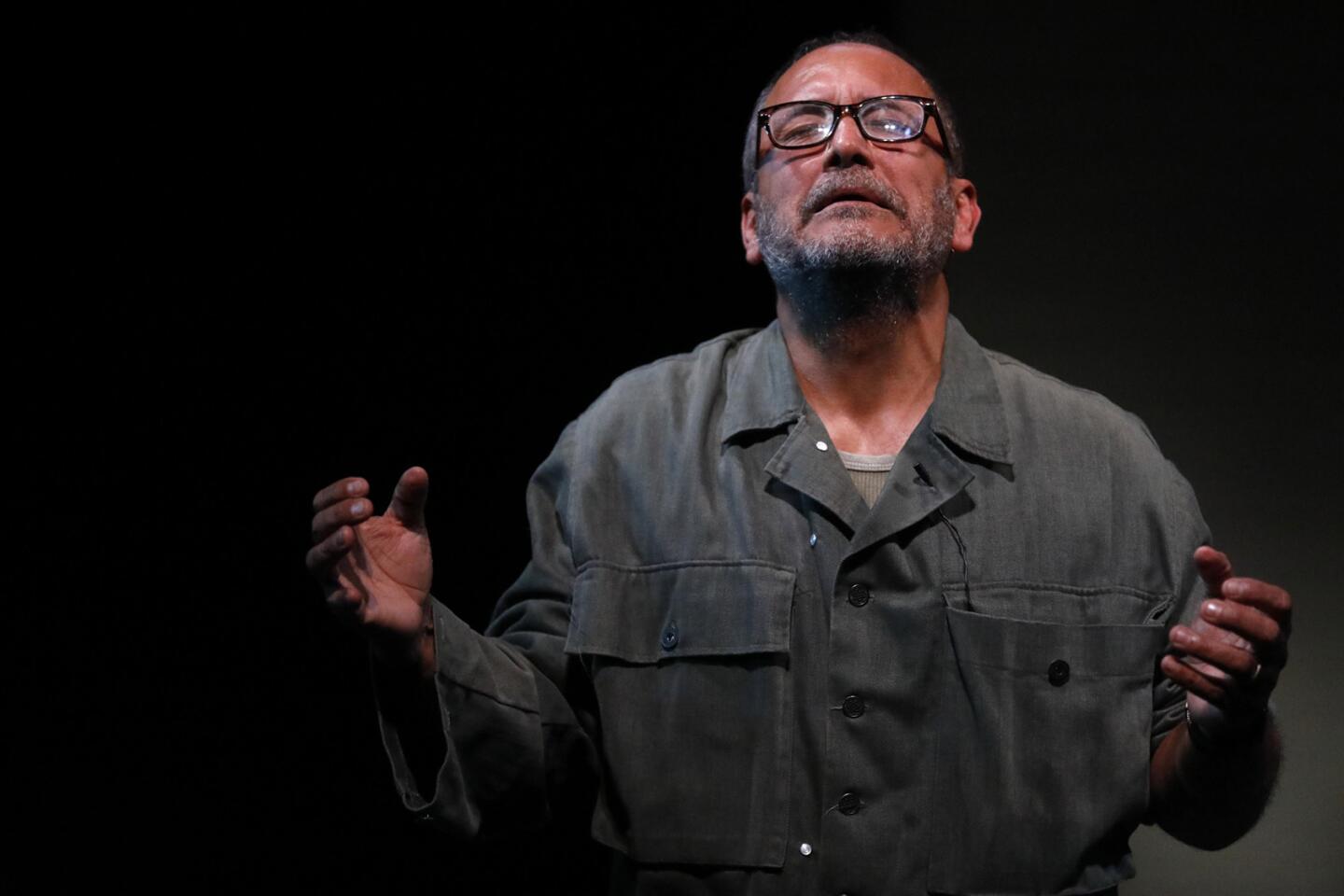

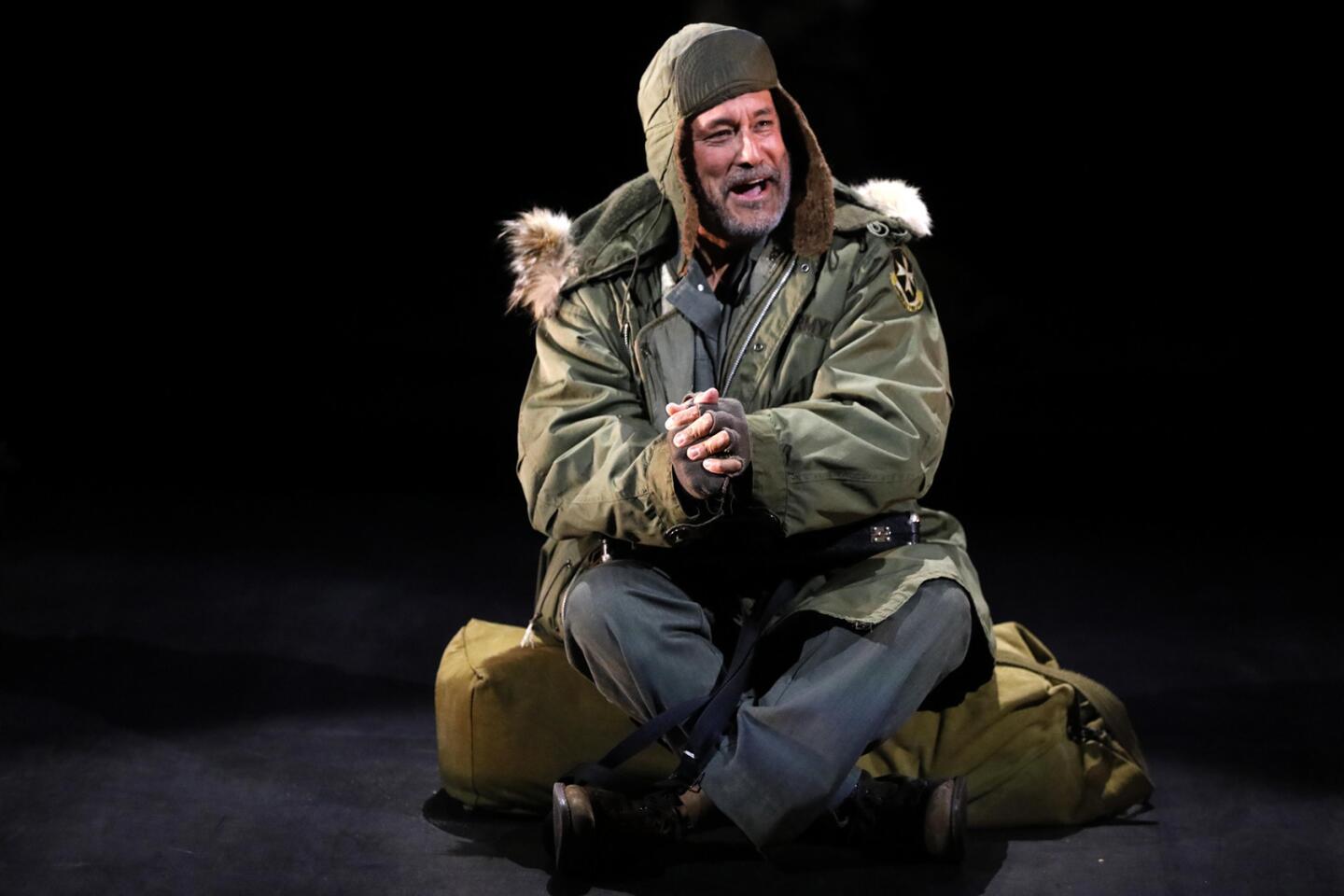

Grandpop (Rubén Garfias), who brought his flute to Korea, where he soothed his fellow soldiers with Bach during lulls in the fighting, enlightens us on the special qualities of a musical form he compares to an argument: “The voice is the melody, the single solitary melodic line. The statement. Another voice creeps up on the first one. Voice two responds to voice one. They tangle together. They argue, they become messy.”

How to sort the major and minor keys, “all at once on top of each other”? Grandpop, speaking as much for the playwriting as for himself, explains, “It’s about untying the knot.”

The knot here has to do with identity — ethnic, cultural, familial, professional and communal — each strand asserting its prerogative as it entwines with the others. Parts may vanish in the jumble, but loosen one section and another hidden facet returns.

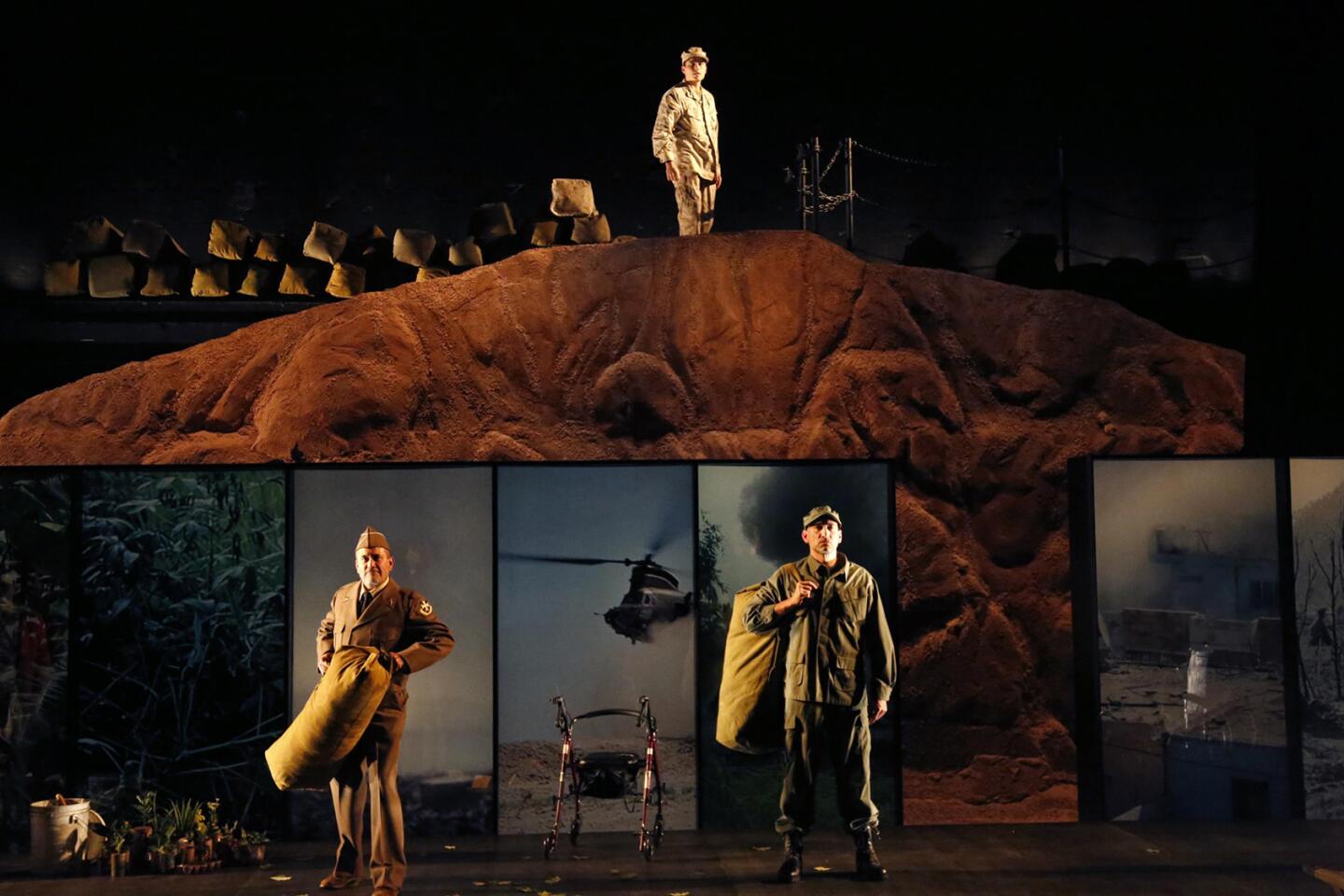

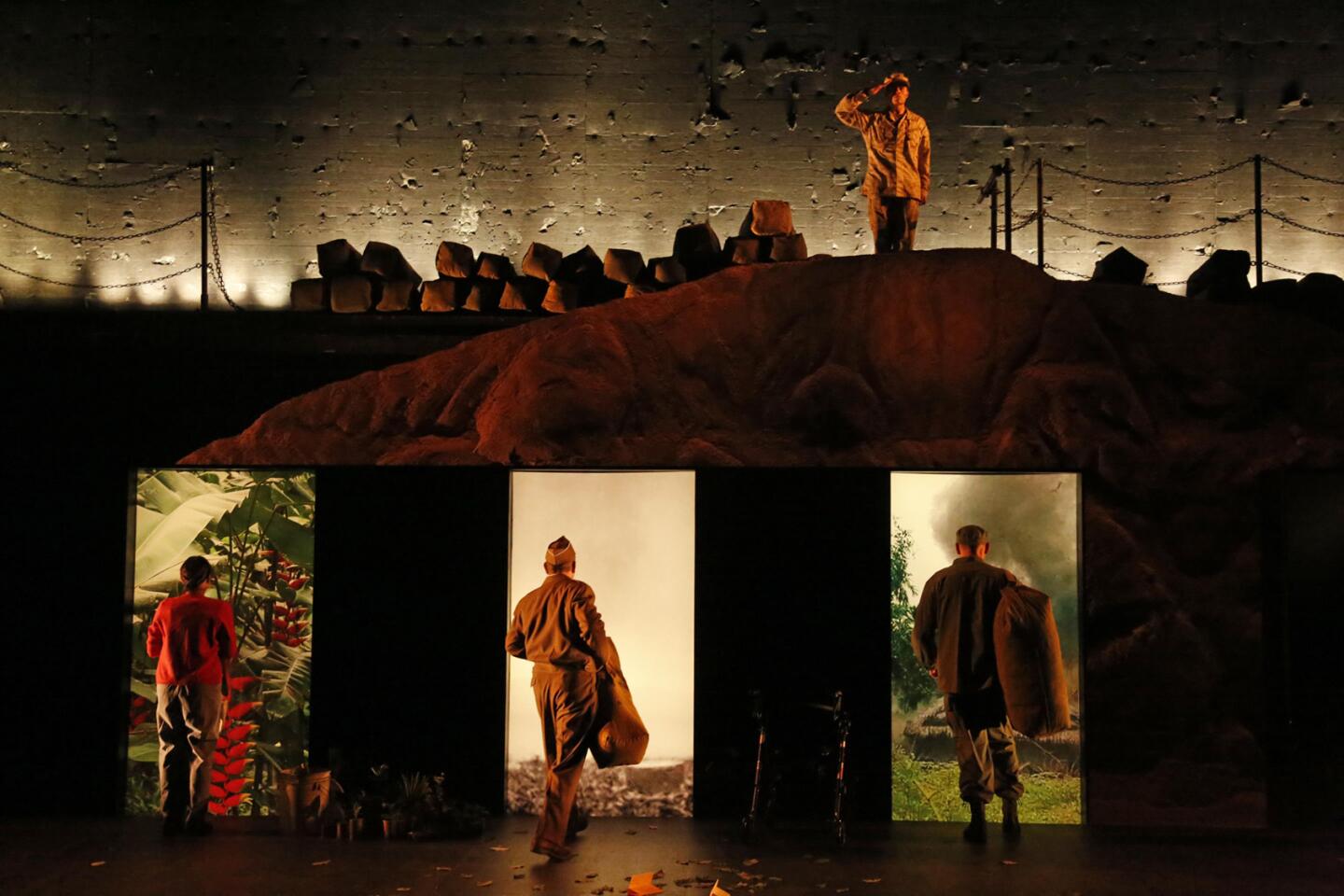

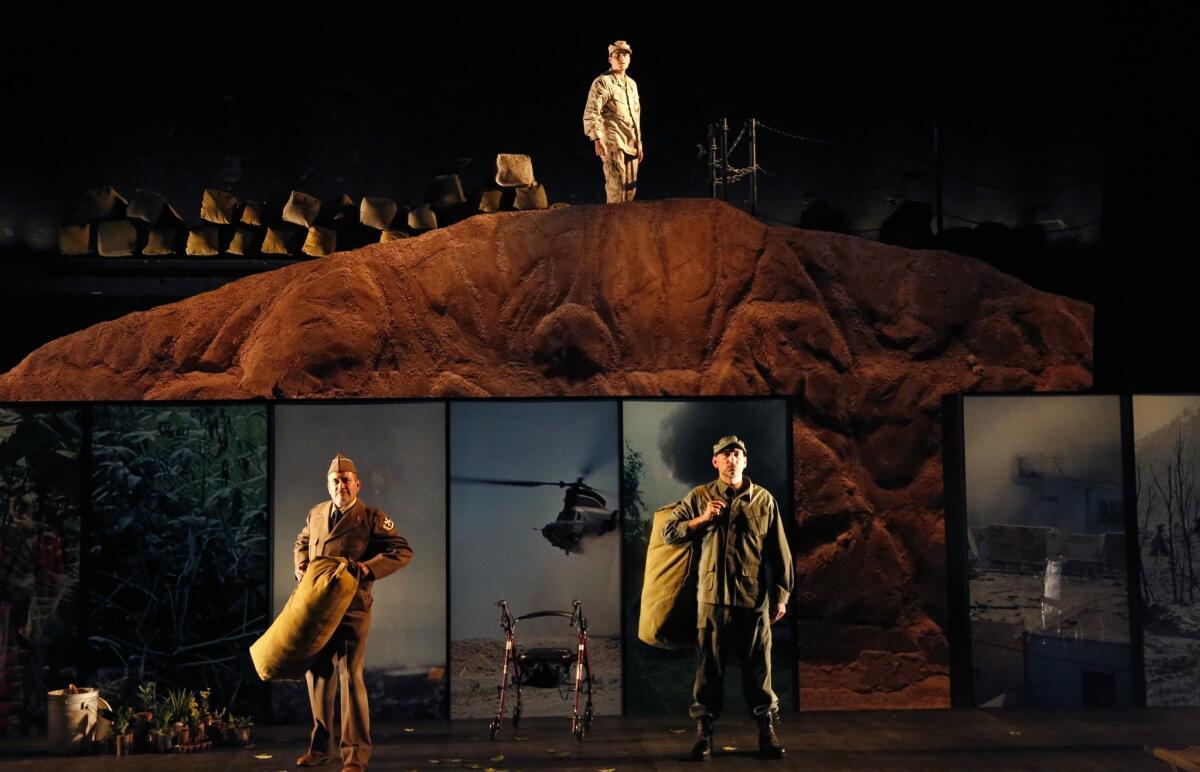

In Shishir Kurup’s production, unfolding on a darkened set with a mirrored backdrop, voices take primacy in a play that poetically alternates between narration and dramatization. The voices are embodied in characters, but the wartime stories they tell bleed across boundaries.

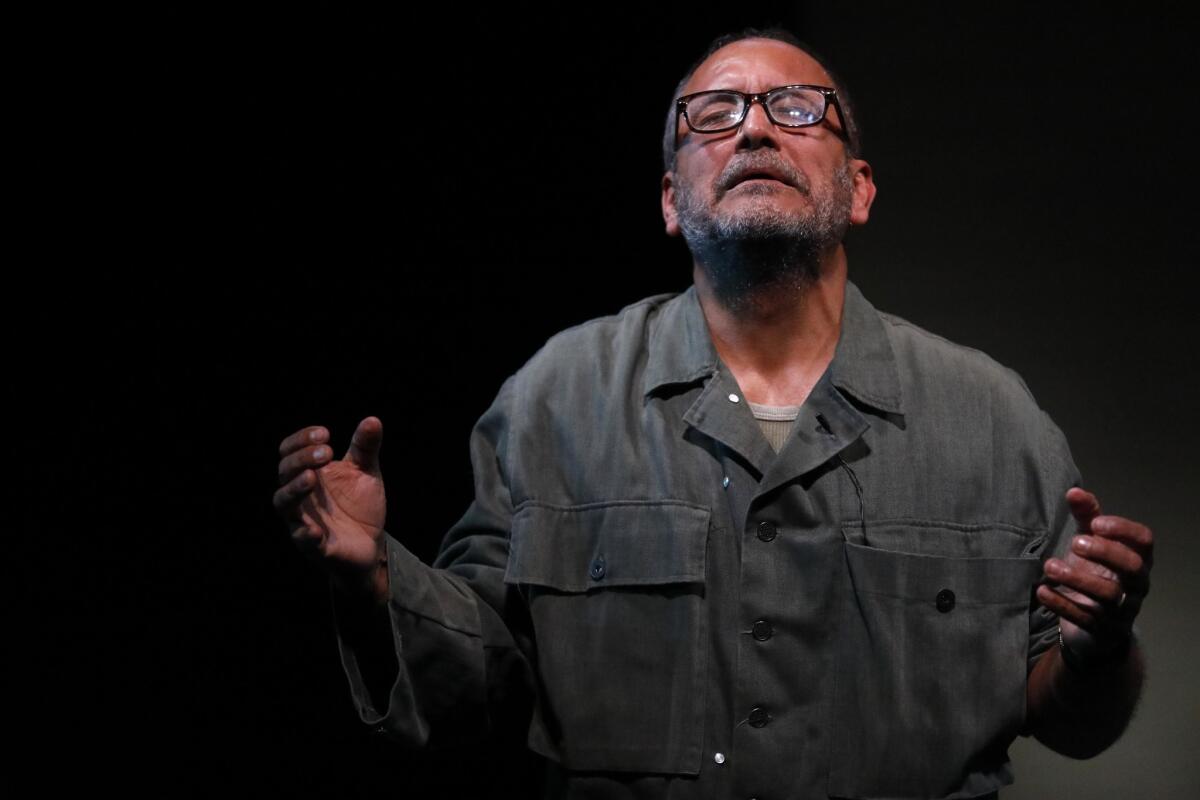

Pop (Jason Manuel Olazábal), who served in Vietnam, where he met Ginny (Caro Zeller), a nurse with a sensuously healing touch, carries his father’s flute along with shared values, remembrances and scars, some of which he has pushed out of view. Grandpop, whose memory is fading with old age, recalls bits of his combat experience, which prefigures what happens to his son and grandson.

The traumatic tales echo one another. The assimilation to hostile conditions, the initiation into killing, the grievous bodily harm that inscribes the war permanently on minds and limbs constitute an uncanny refrain.

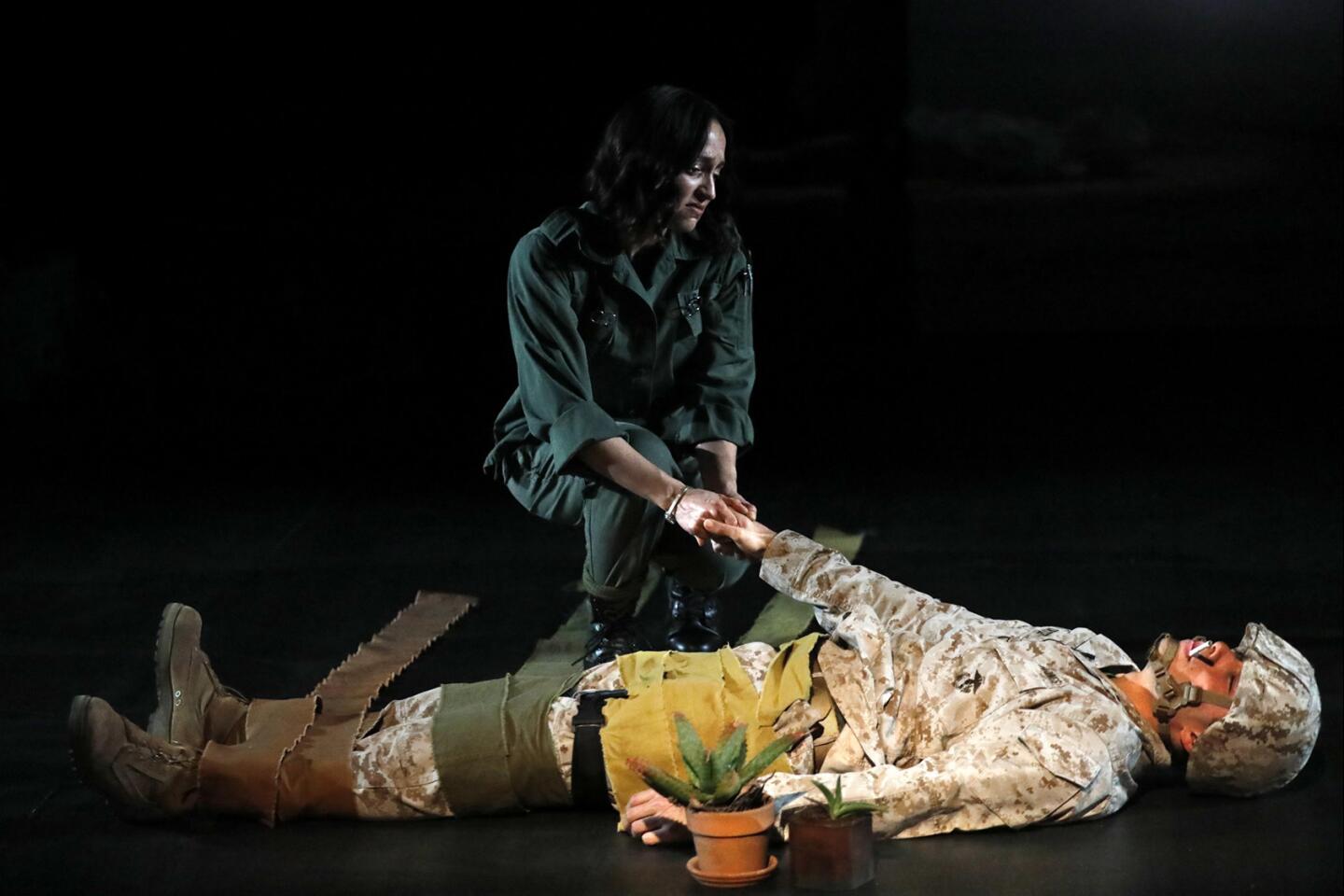

Ginny, who spends time in the garden she cultivates for the benefit of her neighborhood, has aligned herself with the forces of life. Her planting has increased since Elliot has left for Iraq. Each seed, she says, “is a contract with the future,” an expression of faith that “something better will happen tomorrow.”

Hudes lays out the trilogy’s central thematic material in “Elliot,” but many of the threads will be more fully developed in the later plays. Issues of class are touched on — Elliot, for instance, believes that the only alternative to the military is a job making sandwiches at Subway — but will be dealt with more explicitly in “Water by the Spoonful.”

What distinguishes “Elliot, A Soldier’s Fugue” is the potent way it grapples with the physical pain of wartime injuries. The suffering that Elliot experiences replicates what Pop undergoes, a history that Elliot only takes in after Ginny shares with him letters that Pop wrote to his father from Vietnam. These missives were moldering in the basement, packed away like so much of the past that Pop would rather put behind him.

In capturing Elliot’s youthful innocence and vigor, Mendoza raises the emotional stakes for the audience as the young Marine descends into hell. Elliot’s inevitable brush with death raises questions about the cycle of suffering the men in his family have all undergone and kept under wraps. The physical pain, while undeniably real, becomes a metaphor for later psychological misery.

Olazábal’s Pop communicates through his detachment a sense of betrayal. War is nothing like the movies or the patriotic tales that circulate to buck up morale — a lesson that his son can only learn for himself. Guilt and resentment press on him from both generational sides.

Grandpop can’t recall much about his travails in Korea beyond the music he played. Garfias’ Grandpop, lighting up when talking about the flute, conveys the sense that it was Bach that rerouted his mind from despair.

Zeller’s Ginny is most memorable in her hospital flashbacks with Pop in which she flirts with him to restore him as a man. More than her lyrical musings about gardens, it is her boundless love that transforms the broken men around her.

Sibyl Wickersheimer’s set and Geoff Korf’s lighting might be colder than necessary. The ambience is modern but not particularly inviting. These choices are, however, thematically appropriately for a play that travels to places that can neither be vividly remembered nor once and for all forgotten. The scenes exist in forbidding shadows.

By the end, Kurup’s staging locates the painful yet persevering lyricism of “Elliot, A Soldier’s Fugue.” It’s an ideal preparation for “Water by the Spoonful,” a play that will explore the dissonance in Elliot’s life from a wider communal perspective. Whatever you do, don’t miss the middle masterpiece.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

‘Elliot, A Soldier’s Fugue’

Where: Kirk Douglas Theatre, 9820 Washington Blvd., Culver City

When: 8 p.m. Tuesdays-Fridays, 2 and 8 p.m. Saturdays, 1 and 6:30 p.m. Sundays; ends Feb. 25 (call for exceptions)

Tickets: $25-$70 (subject to change)

Info: (213) 628-2772 or www.centertheatregroup.org

Running time: 1 hour, 15 minutes (no intermission)

Follow me @charlesmcnulty

MORE THEATER:

The drama that is ‘Doggie Hamlet’

The glorious mess of Bernstein's ‘Mass’

‘All the President’s Men,” a revival with relevance

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.