Review: The artwork of Adrian Piper makes a stern proclamation: ‘Everything will be taken away’

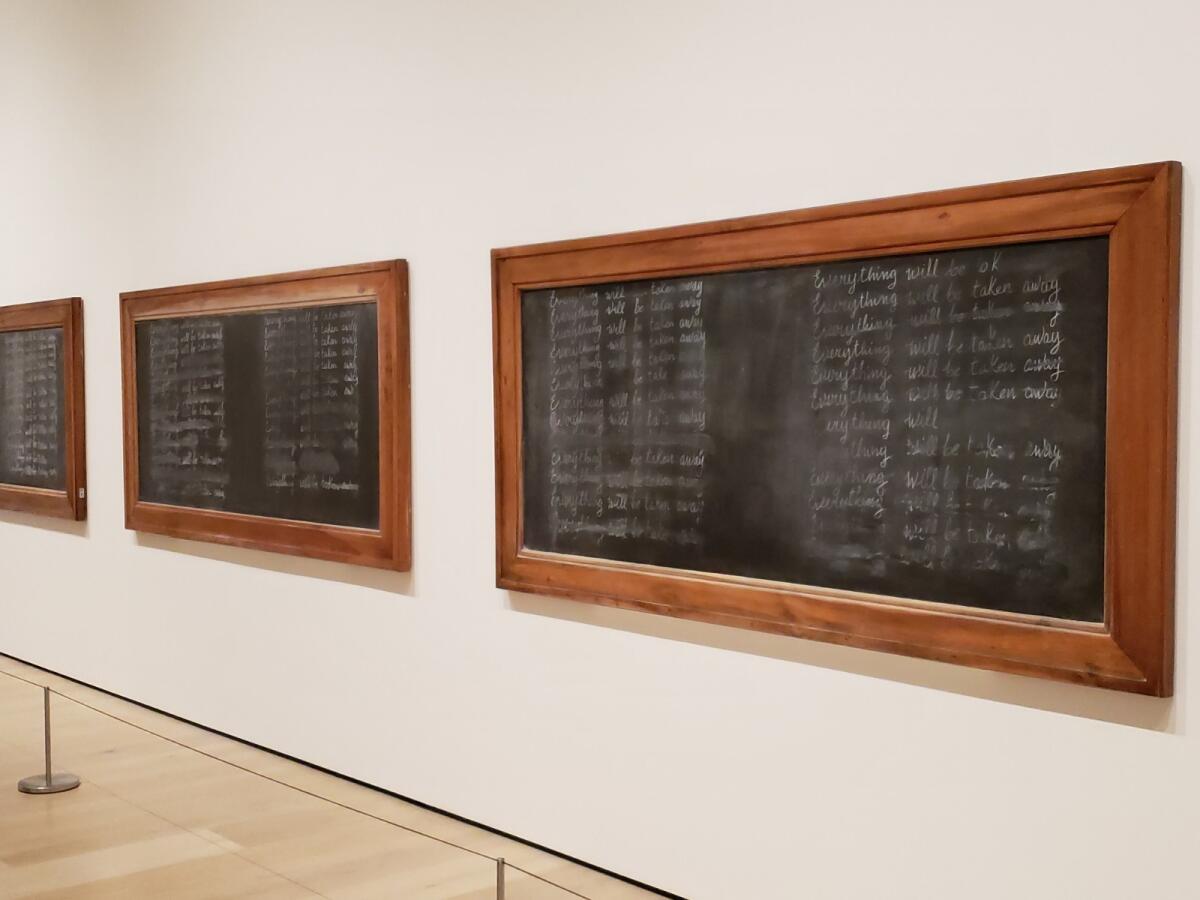

Near the end of the UCLA Hammer Museum’s big retrospective exhibition of American expatriate artist Adrian Piper, who has lived in Berlin since around 2005, four vintage blackboards spell out a theme the artist has engaged for many years. A single sentence is repeated over and over again in neat rows, written in chalk in the manner of a classroom punishment — the kind a naughty schoolgirl might be required to complete.

The outlook is brusque: “Everything will be taken away.”

The cursive penmanship is graceful and precise — practiced and assured. Some words are smudged, a few completely erased. The rest could be wiped clean with an easy stroke. Taken away.

On one hand, the blackboard exercise is a simple still-life on the theme of mortality and loss. It’s a Conceptual art interpretation of an old vanitas motif in painting.

In place of overripe camellias on the brink of wilting, a snail munching holes in green leaves or a fresh but bitter lemon peel unfurling in a continuous downward spiral from a sumptuous plate of fruit, Piper gives us a classroom lesson: Sooner or later, everything is gone.

But there’s more to it than that — even though that might be quite enough.

Piper is one of those artists whose work unpeels like an onion, layer upon layer, perhaps betraying her other professional capacity as an academic professor of philosophy. (Piper, 70, earned a Harvard PhD in the subject in 1981.) The word “taken” implies the possibility of unwilling removal — or even theft — rather than natural decay.

African American (both her parents are biracial), Piper inserts a suggestion of autobiography into the mix. Society, not just nature, can be the agent that takes everything away. The handwriting is on the wall.

Yet, all is not bleak — a dirge of forfeiture and death. An important aspect of Piper’s blackboard is that it recalls several other, earlier works of art.

In 1971, Los Angeles Conceptual art pioneer John Baldessari famously instructed students at Nova Scotia College of Art and Design to write “I will not make any more boring art” on gallery walls, later making a video and print of the installation exercise. A few years later, German Conceptualist Joseph Beuys made a series of drawings on blackboards, each executed during public lectures on art and politics.

In the 1990s, Gary Simmons, an African American artist like Piper, began to make “erasure drawings” — bracing images in chalk on blackboard that are forcefully scuffed and smudged but hanging on for dear life. Black experience in America is their subject, as in a monumental example related to vintage films that feature African American casts, currently at the California African American Museum in Exposition Park.

Everything will be taken away — but as long as the conversation among artists persists, so does cultural community. Art is born of other art.

When a gallery attendant passes by in the exhibition while wearing a sandwich board printed with the blackboard’s warning text, Piper gives us a sly if sober bit of witty self-awareness. She might be like that cartoon doomsayer shaking a fist at the sky (and at passersby) to declare, “The end is nigh!”

The Hammer retrospective, organized by New York’s Museum of Modern Art, is the largest show of her work to be seen in Los Angeles since 2000, when “MEDI(t)Ations: Adrian Piper’s Videos, Installations, Performances, and Soundworks 1968-1992” appeared at the Museum of Contemporary Art. With more than 270 works — plus a large-scale 1991 mixed-media installation, “What It’s Like, What It Is #3,” addressing racist stereotypes, off-site in the project room at downtown’s Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles — it’s the kind of exhibition that will require repeat visits to fully take in.

I suggest beginning by devoting a good deal of time to early work in the entry room. Many parameters that are elaborated over the next 50 years are sketched out.

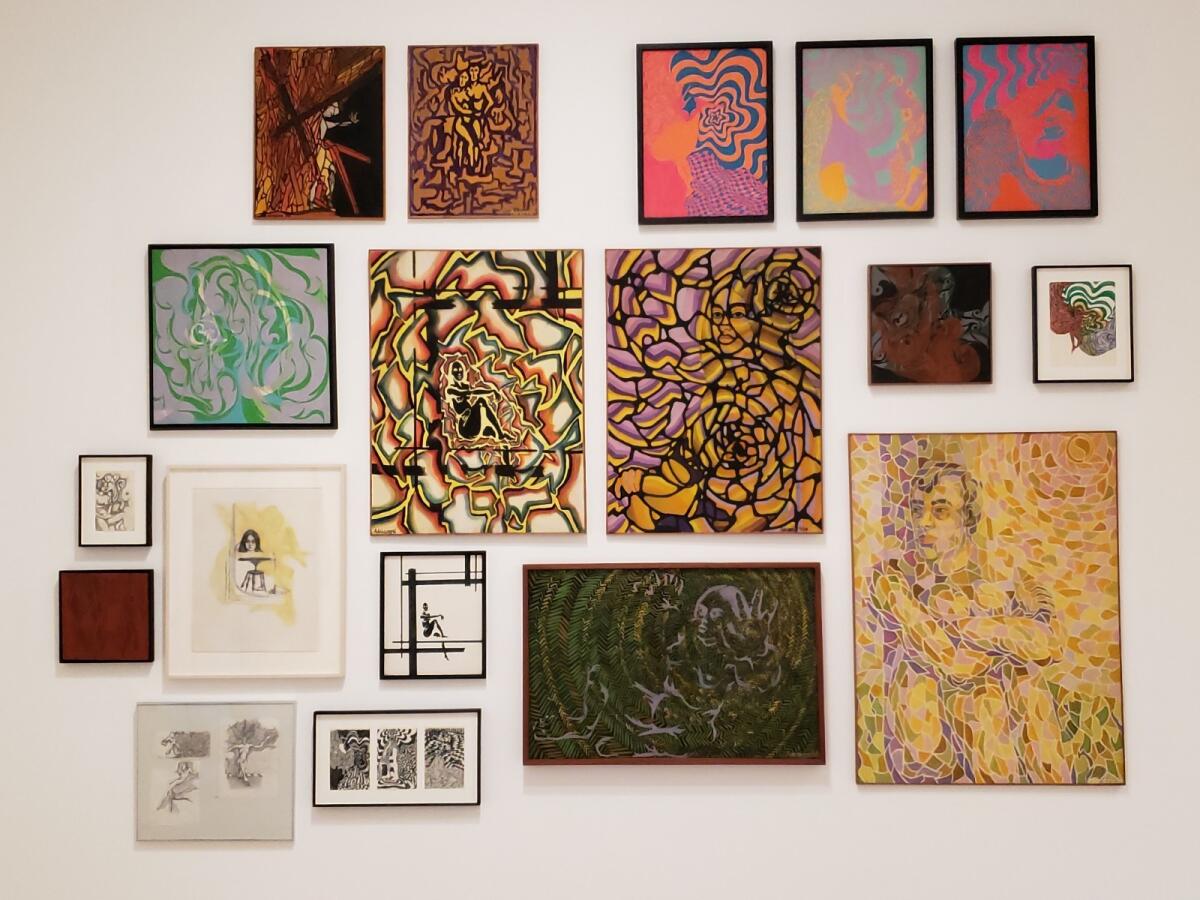

First is a wall covered with 22 psychedelic drawings and paintings made under the influence of LSD in 1965 and 1966. Piper was a teenager. Suggestions of human figures mesh with abstract swirls, patterns and marks of bright color.

Forthrightly bridging the period’s stark aesthetic divide between figurative and abstract art, yet not formally accomplished in the sense of traditional paintings, they nonetheless put the artist’s desire for altered perception front and center. Messing with common awareness would mark virtually all of her subsequent work.

These youthful examples would also differ from everything that came after, simply by being the last moment when color would play an important role. Almost the entire show is in black and white. Charcoal, pencil, printed texts, research binders, gelatin silver prints, newspaper ads and columns, Instamatic snapshots, photocopies, early videos — these and other materials dodge chromatic play.

Color was a foe. In the 1960s and early ’70s, a narrow range of poured, sprayed and thickly troweled Color Field painting was being advanced as the victory of an establishment avant-garde. Piper’s art plows it under.

Across the way from the psychedelic paintings, 35 “Barbie Doll Drawings” in pencil and ink on notebook paper rearrange the toy’s body parts. A corporate-designed male ideal of white femininity, circa 1967, is gleefully dismantled. Piper, just 18 at the time, tore it limb from limb, then reconstructed it in dozens of imaginative, Surrealistic ways.

In between Barbie and psychedelia, culture and counterculture, two geometric sculptures are installed. One is a recessed black square within a protruding white frame on the wall; the other is a step-down, double-recessed white rectangle on the floor. As with a group of geometric drawings nearby, they demonstrate the profound impact artist Sol LeWitt had on Piper’s direction.

Compared to the surrounding works, these two spare geometries arrive with the force of a thunderclap. The exhibition is dedicated to LeWitt, whose Minimal and Conceptual structures were rigorous in removing the artist’s subjectivity from an art object’s form. Piper followed suit.

For instance, she made a series of photo-text works that document the process of submerging metal plates in trays of sulfuric and nitric acid. She is, in effect, employing an etching technique developed in the Renaissance, in which a line drawn into a coating on a metal plate would be incised with acid. Except, here, something is missing.

Nothing is drawn on the metal plates in Piper’s snapshots. Rather than create a picture and print an image, she documents the metal plates dissolving in the acid bath.

Everything, you might say, is being taken away.

Immersion in those first works from the late 1960s provides a template through which subsequent galleries can be productively approached. Piper’s work can be opaque and uninvolving, especially when it consists of charts, densely typed sheets of research and image-text aggregations. None of it is pointless, but sometimes experiencing the work can feel like homework.

Race is her great subject, and it is bracingly unraveled as a stubborn fiction in drawings like the 1981 “Self-Portrait Exaggerating My Negroid Features.” The face that looks back at us, head-on like most any artist’s self-portrait drawn while looking into a mirror, appears to be perfectly ordinary. But she summons a viewer’s prejudices to decide exactly what those “exaggerations” might be.

Two years later, she made one of the show’s stand-out pieces — the very funny film “Funk Lessons,” transferred to projected video. Piper tutors an eager group of mostly white young people in the rhythmic moves of soul dancing. The format is “American Bandstand” by way of “Soul Train,” the kids moving in ways awkward or soulful, cadenced or clumsy, to the immersive and seductive sounds of “Funkytown,” the global dance hit by the group Lipps Inc.

Piper cheerfully instructs them in assorted body moves using the elevated, post-structuralist language of a university professor. As in the self-portrait, she lampoons the very concept of racial identity as something inherent. The concept of race is taught, much the way racism is a learned behavior.

If there’s a surprise to the retrospective, perhaps it is the degree to which her sometimes parched but never ungenerous Conceptual program exerts a spiritual dimension. Shared humanity is a through-line in Piper’s work.

“Conceptual artists are mystics rather than rationalists,” Sol LeWitt famously wrote. Piper’s fascination with the fundamental nature of existence animates her study of philosophy, and it’s right there in her antique blackboard piece. Repetition is ritual, the reiteration of a mantra on mortality a soulful sound.

UCLA Hammer Museum, 10899 Wilshire Blvd., Westwood, (310) 443-7000. Through Jan. 6. Closed Monday. www.hammer.ucla.edu

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.