Unorthodox L.A. opera genius Yuval Sharon arrives on the world stage

The opening day of the Bayreuth Festival is always July 25; it is Germany’s most exclusive cultural event of the year. Chancellor Angela Merkel is a regular, as are other top German and European officials, business leaders and socialites, and scandal, artistic bickering and theatrical provocation are part of the tradition.

Two summers ago, the Latvian conductor Andris Nelsons stormed out on short notice after bickering with the festival’s music director. Last year, the festival was forced to face its early history of Wagnerian anti-Semitism first hand via an in-your-face new production of “Die Meistersinger” by Barrie Kosky, the first Jewish director to stage an opera at Bayreuth.

This year, the issues began when Alvis Hermanis, scheduled to direct the opening-day new production of “Lohengrin,” vacated the Green Hill, as the festival site is known, presumably for political reasons. Opposed to Germany’s inclusive immigration policy, the Latvian director had also pulled out of a production in Hamburg.

Bayreuth’s replacement will be its first American director, its second Jewish director and one who has developed and staged opera about émigrés performed on site in downtown Los Angeles and Boyle Heights.

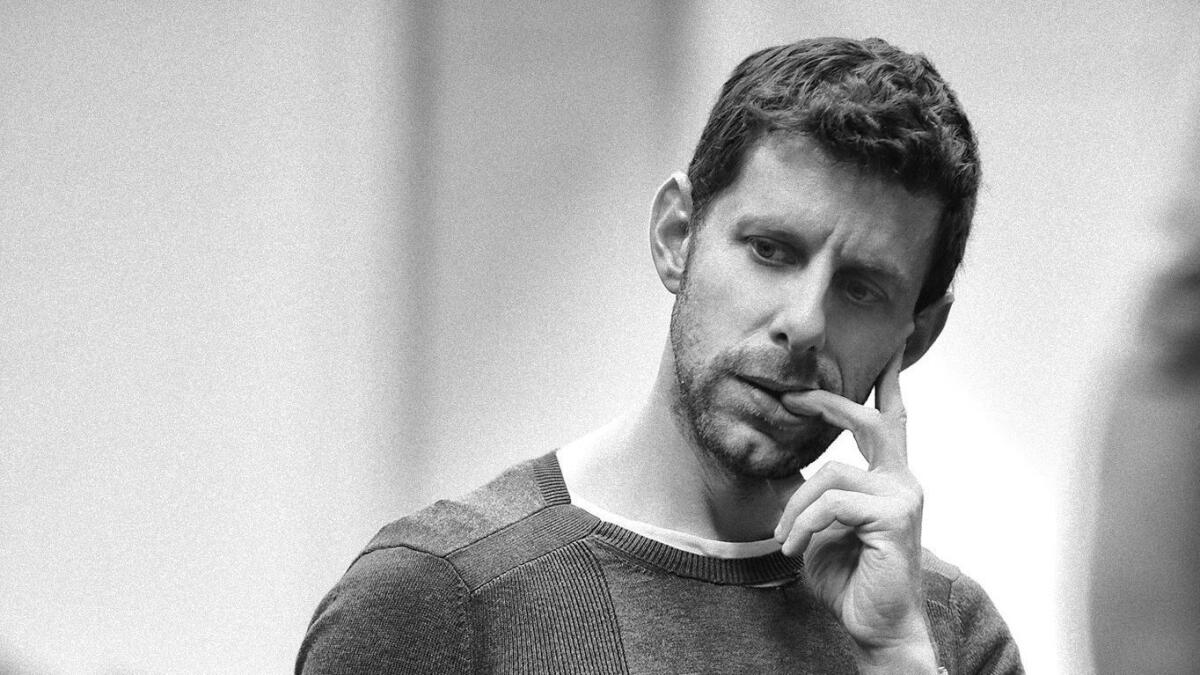

Predictably, the selection of Yuval Sharon has created a significant international operatic stir.

Founder of the revolutionary L.A. opera company, the Industry, and a recipient of a 2017 MacArthur Foundation “genius grant,” Sharon is also the Los Angeles Philharmonic’s wildly imaginative and gleefully disruptive artist-collaborator. He was the mastermind behind Annie Gosfield’s riotously effective operatic “War of the Worlds” at Walt Disney Concert Hall and on location in DTLA last fall.

Bayreuth certainly felt far away when I met with Sharon in a sushi bar in Little Tokyo (where the Industry offices are) a couple of days before he left for Germany to begin “Lohengrin” rehearsals. His latest project had been a surprise appearance a month earlier at the Broad, where he made his debut as a conductor for John Cage’s Concert for Piano and Orchestra, part of a program of Cage’s music in connection with the museum’s Jasper Johns exhibition.

He was just back from unsettling an opera conference in Madrid, Spain, where the 39-year-old director advocated, mostly to deaf ears, the idea that the opera world would do well to follow the lead of contemporary theater. “No one questions Shakespeare rearranged,” Sharon explained after savoring a delicately sliced piece of toro, “cut, refigured, recast, additional texts put into it. Some people might still say that’s a crime against Shakespeare, but not too many. Most people realize this is how these works stay alive. But opera has not taken that leap.”

It won’t exactly take that leap in Bayreuth either. The artistic staff of Bayreuth was nowhere to be seen at “Hopscotch,” the operatic extravaganza Sharon conceived and spectacularly instigated in 2015, putting the Industry on the map in more ways than one. Having commissioned a dozen composers and librettists and navigated his way through a mountain of city regulations, Sharon mounted his mobile, immigrant-themed “Hopscotch” in limousines and historic downtown theaters, under freeway underpasses, on the roofs of buildings, in Chinese and Latino plazas.

Instead, Sharon came to the attention of Wagner’s great-granddaughter Katharina Wagner, who heads the Bayreuth Festival, through his work in Europe. Over the past four years he has been responsible for a prize-winning staging of John Adams’ “Doctor Atomic” in Karlsruhe, Germany, followed by Wagner’s “Die Walküre,” as well as Peter Eötvös’ “Three Sisters” at Vienna State Opera. While never less than imaginative, none of these productions was radical for Germany or Austria, where modern directors go out of their way to create controversy with outrageous novelty.

Sharon’s deep respect for music, along with his intellectual rigor, were clearly the deciding factor for Bayreuth. He always begins at the beginning, with the music and the composer’s original intention, seeing where that leads him before beginning to dice and slice, even when he has proposed, so far again to deaf ears, staging “La Bohème” backward-- Act 4, Act 3, Act 2 and Act 1 – and without break.

“I’ll use the old production, just give me the sets and costumes but I’ll put it in the opposite order on one hand, because it will work really well, from devastation to the beginning. Some people might even think it’s the way it’s supposed to happen. But on the other hand, to hear the music in a new way.

“That’s the point of that piece. You can put it on the moon or anywhere else and it’s still the same old ‘Bohème.’ But how do you get to the core of this piece if not by radically transforming our ability to listen to this piece and thereby open a door to a way that we’ve never thought about it before? So if we end in Act 1, with them singing offstage with these high C’s, what a wonderful way to end on opera.”

Indeed, in Sharon’s grand scheme for grand opera, one thing is also meant, in ways large and small, to lead illuminatingly to another.

“Isn’t that how we listen to some things these days?” he asks. “In the car, I just put a bunch of things on shuffle. So all of a sudden I’ll get these wonderful strange leaps from one time to another, or from one opera to another. Even jumping around within the same opera, all these unexpected relationships emerge.”

The epitome of this was in “Hopscotch,” where the audience hopscotched through an exuberant nonlinear narrative, musical and scenic maze.

But what the die-hard Wagnerians at Bayreuth could not possibly have understood is exactly the kind of essential Wagnerian Sharon happens to be.

He is, of course, the most unlikely of Wagnerians. Born in Chicago to Israeli parents, Sharon spent his first three years in Israel, where Wagner is not performed. He has an affable, upbeat manner and is very fast to laugh, which is hardly the way one thinks of the intense, bigoted, Messianic – and no doubt mesmerizing in person -- Wagner.

Sharon, moreover, is seductively drawn to the most adamant of all great anti-Wagnerian composers, John Cage. Not only has he now become the first opera director to ever conduct Cage (in the case of the “Concert,” which is for piano and any number of other instruments, including none, that means standing and moving your hands like a human clock), he will stage Cage’s “Europeras 1 & 2” with the L.A. Phil in November.

Even so, Wagner lies at the center of Sharon’s operatic being. He describes his father, a nuclear scientist, taking him to opera in Chicago in his early teens by saying that “it really didn’t speak to me at all, but it was a really nice thing to do with my dad.

“And the first opera I didn’t hate was ‘Siegfried’ [the third opera in Wagner’s ‘Ring’ Cycle]. There was the sword and the dragon. I just hated the love duet. As a 13-year-old, give me a break. Now that’s my favorite part of ‘The Ring.’”

He has even suggested staging Act 3 of “Siegfried” all by itself as an evening’s work, “because the music of that act is so advanced as are the ideas, but when it’s in a full Ring Cycle you’re always too tired to properly appreciate it. But when I pitch ideas like that and “Bohème” to opera companies, they always turn me down.” This explains why Sharon has yet to work with a major American opera company. The Met and the other important and equally cautious companies in this country are not exactly known for taking such artistic chances.

Sharon caught the opera bug as an English major at UC Berkeley, where he started a student theater company. The light went on when, during an opera appreciation class, he heard Meredith Monk’s hypnotic “Atlas.”

“I thought, ‘Oh, wait, there is a possibility for opera to become totally different from what I had experienced,’” he recalls. “Meredith’s music speaks to you immediately. It has a directness that is so uncanny it transcends the genre.”

From that moment on, Sharon says, his dream has been to stage the opera, which was given its premiere in Houston in 1991. For the last project of his three-year L.A. Phil residency, Sharon will come full circle making a new production of “Atlas” next June.

It appears to have been Sharon’s want from an early age to think about time and structure in reverse order, and consequently he learned opera by working back through history. When he discovered Wagner’s idea of a total artwork, or Gesamtkunstwerk, that includes visual, theatrical and musical elements, he found his calling. A year in Berlin after graduation became Sharon’s real opera and theater education. Exposure to the progressive opera and theater in Berlin, where Sharon spent a year bumming around after graduation, set him on his way.

He moved to New York to start a small, but typically ambitious theater company, starting, despite a shoestring budget, with Aeschylus’ “Oresteia” trilogy. Already enchanted by the notion of presenting a plurality of ideas on stage, he brought in two other directors to each take one play.

For his day job, Sharon worked at New York City Opera, first in administration and then running Vox, the company’s program of workshopping scenes from new operas. Restlessly wanting to try his hand with full opera productions, he moved on to freelance and learn the trade by assisting opera directors, including working with Graham Vick on Wagner’s “Tannhauser” in San Francisco.

The real breakthrough came in 2009, when Sharon was invited to assist Achim Freyer in Los Angeles Opera’s production of “The Ring” in 2009. Freyer is also an avant-garde visual artist and a deep philosophical thinker, and then there was L.A., itself.

For Sharon, the teeming 21st century multicultural city had all the qualities of a vast Gesamtkunstwerk stage, just the place to undertake a modern day Wagnerian experiment, so he stayed and founded the Industry. This would be a company where mostly young and mostly L.A. visual artists, writers, dancers, choreographers and composers could collaborate on work that would become part of the fabric of the city.

“Hopscotch” was the extravagant third part of a kind of “City” opera cycle, that began with Anne LeBaron’s “Crescent City,” mounted as an art installation, and Christopher Cerrone’s “Invisible Cities,” staged in waiting areas of Union Station; the audience listened on headphones while travelers and others went about their usual business.

This conviction of art as an immediate reflection of and direct entry into the world around us best explains why the invitation to Bayreuth, the birthplace of modern operatic Gesamtkunstwerk, immediately resonated with Sharon. A further draw was the two German visual artists, Neo Rausch and Rosa Loy, who had been engaged to make the sets and costumes.

“They were on board before I got there,” Sharon says. “They had some initial ideas that they really wanted to keep, which is a working structure that I feel very sympathetic to. It’s not about me coming in and delivering an essay on ‘Lohengrin,’ and leaving. I’ve never seen myself as the auteur-like director. To me that feels dishonest in a field like opera.”

That is not to say that there hasn’t been friction. Probably the least attractive aspect of this project was the casting of Roberto Alagna in the title role. There were questions from the start about a lyric French tenor who doesn’t know German and had never sung a Wagner lead taking on the title role. With three weeks to go before the first performance, Alagna announced that he hadn’t had enough time to prepare and left the production. Quick work and good luck cleared the way for the Polish tenor Piotr Beczala, one of today’s best Lohengrins, to join what is now a first-rate cast that includes soprano Anja Harteros and mezzo-soprano Waltraud Meier.

Success or scandal, Sharon knows that Bayreuth will change his place in the opera world. Invitations from all over are sure to pour in, most likely from Europe given how his ideas tend to bewilder the more conservative American companies. But he says he plans to stick to his guns. He is already booked through next year, with projects for the L.A. Phil; a new production of Olga Neuwirth’s “Lost Highway,” an arresting electronic opera based on the David Lynch film, at Frankfurt Opera in September; a new production of Mozart’s “The Magic Flute” in Berlin next season; and various things he is cooking up for the Industry.

After that, he says, he will use his MacArthur funds to spend a year in Japan, where he has never been, soaking up the culture, especially Noh theater. “2020 is a black hole,” he enthuses. “I want to take that year to really figure out what I really want to do, what’s the next step.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.