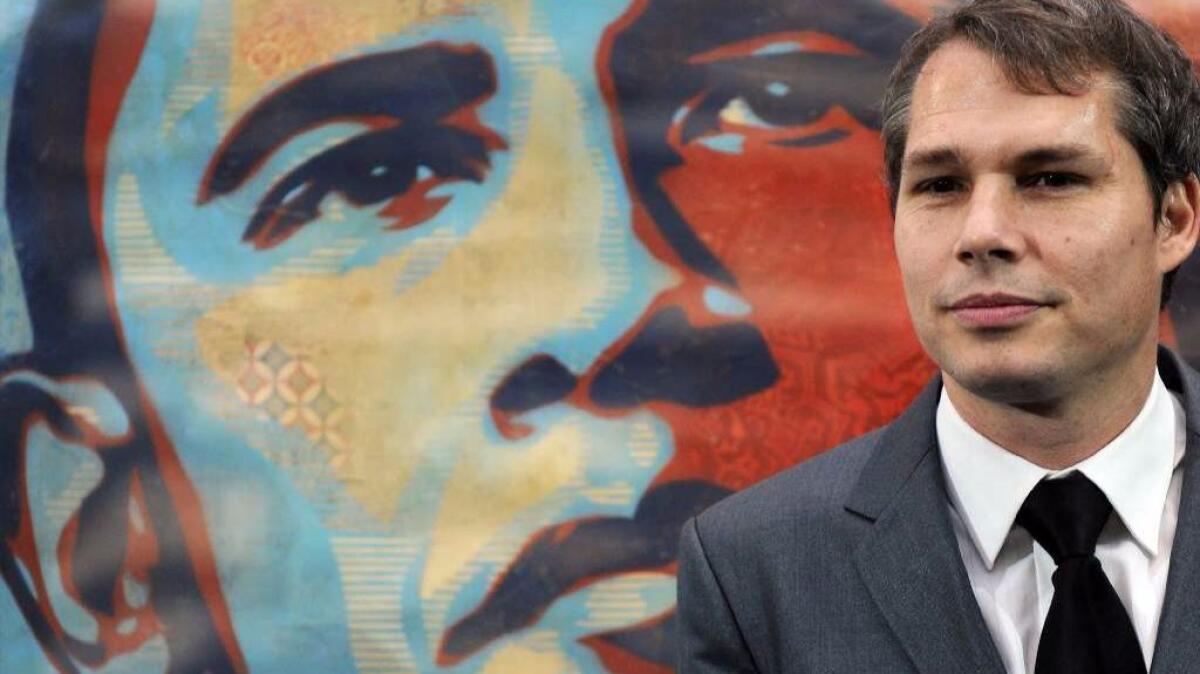

Shepard Fairey: Have we lost the ‘street’ in street art?

The thing about Shepard Fairey is: He refuses to obey. The street artist and graphic designer who created the “Hope” poster during Barak Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign is the subject of the Hulu documentary “Obey Giant,” premiering Saturday. The movie, directed by Oscar-winning filmmaker James Moll and executive-produced by James Franco, chronicles Fairy’s personal story, from his Charleston, S.C., skate-scene roots to his rise as a veritable brand of iconoclasm. It also explores the wider world of street art and how it intersects with activism, punk rock and politics. Which begs the question:

With the commercialization of street art in advertising, movies, TV, even video games, is the medium “street” anymore — and does it have the potential to activate viewers politically in the way it used to?

To me, it’s all valid in different ways. I’ve been asked to have my stuff in any number of commercial applications that I’ve turned down because it wasn’t true to my sensibility. But then, I’ve also done things that other street artists say “Oh, I’d never do that, I’d never have a clothing line.” But to me, everyone gets up and puts clothing on. And if the clothing is a way of sharing my ideas, my aesthetic, and it’s also a gateway to the rest of my practice, then in some ways it’s a subversive way of infiltrating the mainstream. I guess it comes down to your perspective.

People get numb to anything that is predictable. Street art has some cliché aesthetics, like stencils or drips or tags or any number of things you associate with the medium. But street art is evolving all the time. So I think the power for street art to impact people is always gonna be there. It’s just a matter of finding a way of staying a step ahead of what’s become cliché. That’s something I’ve always tried to do in my work. Maintain consistency on the things I think continue to be relevant and maybe inspire people to empower themselves, but then also evolve so the work doesn’t get stale.

I’ve been very pleasantly surprised to see people come along, like Vhils, who chisels his art out of walls, or Space Invader doing mosaics, or JR shooting photos of people in neighborhoods. To see all these different manifestations of street art that break away from the more predictable street art aesthetics.

But what inspires me is not just the aesthetics, it’s the courage that it takes to go out and do something in public that’s risky. If I see something in an ad, and I know that it was done safely on a set, and I see something with a similar aesthetic but clearly done in a daring way, it might have a completely different impact on me. The visceral reaction of seeing something on the street that was done covertly, I think, is always gonna be more intense than seeing something like that on a gallery or museum wall — or in a movie or an ad for a product.

Follow me on Twitter: @debvankin

ALSO

Postmodern architecture at risk, Part 2: The saga shifts to Chicago

How Plácido Domingo taught L.A. to love opera

Bruce Kaji dies at 91; Japanese American National Museum founder and Little Tokyo pioneer

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.