‘Waitress’ proved the power of women at the box office. Will its success change theater?

They didn’t set out to do it, but when the creative talents behind the Broadway musical “Waitress” assembled in a room, they looked around and realized something unusual: They were all women.

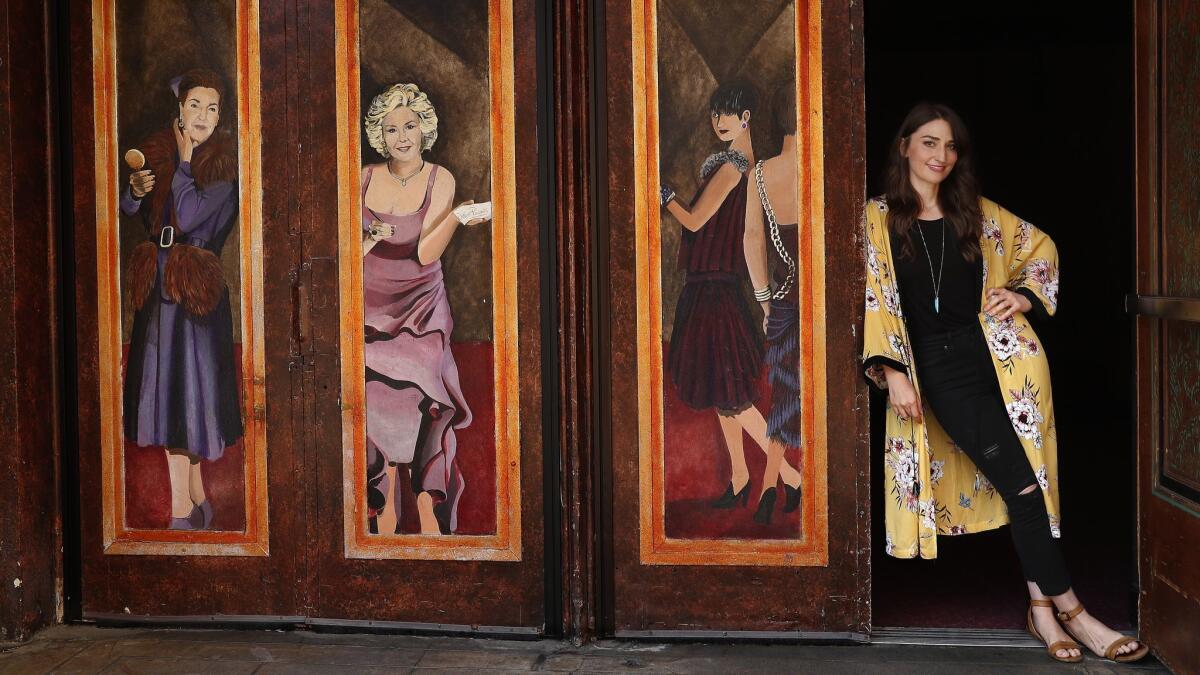

“It’s pathetic that it’s so rare,” says Sara Bareilles, who wrote the music and lyrics for the show, collaborating with book writer Jessie Nelson, choreographer Lorin Latarro and director Diane Paulus. But the ultimate message, Bareilles says, is that they were just people trying to make good, enduring work. “And I think if you make good work, it has the potential to stay — whether you’re a man or a woman.”

“Waitress” has proved its ability to stay. As the musical approaches its 1,000th show on Broadway, it’s also nearing the one-year anniversary of a national tour that has finally arrived on the West Coast, with performances at the Hollywood Pantages Theatre beginning Thursday. The Broadway production has grossed more than $115 million, and productions will launch in Australia and Britain.

With that kind of quantifiable success, has the power dynamic in theater shifted at all? Are more shows with women in top creative positions making it to the stage? A lack of reliable statistics cannot deny the greater truth that many women in the industry feel: that the earth is slowly shifting in their favor.

There’s that awful moment when you realize something new is happening that you thought was happening all along.

— Anna D. Shapiro, director

That women created a hit like “Waitress” should not be remarkable, but it is, says Anna D. Shapiro, who won a Tony Award for directing “August: Osage County” in 2008. Ten years ago, Shapiro was only the second American woman to have won that honor for a play. In the ensuing years, four more women have followed, including Pam MacKinnon for “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” and Rebecca Taichman for “Indecent.”

“There’s that awful moment when you realize something new is happening that you thought was happening all along,” says Shapiro, who’s directing “Straight White Men,” written by Young Jean Lee — the first female Asian American playwright to be featured on Broadway. “And you want to celebrate, but you’re like, ‘Ewww, this isn’t something to celebrate, this is 2018, we should all put on our hair shirts and apologize,’ because you can’t believe how backward we are, and how long it takes for people to get purchase.”

Shapiro is the artistic director of the Steppenwolf Theatre Company in Chicago, another top position where women have yet to see parity. She says the issue isn’t so much latent sexism — although that exists — but the harsh realities of the bottom line in commercial theater.

Broadway is such a high-stakes game that producers tend to court those who have the most established track record of financial success. Because the market has been dominated by white men for so long, an ecosystem has evolved where only a chosen few get a shot at the brass ring.

“We’ve been programmed to believe that white male equals success, and we’ve got to untangle that, we’re better than that,” Shapiro says. “The reason why women and people of color need to have a seat at the table as leading artists in power isn’t because it’s morally right, or that white male stories are boring or don’t matter. It’s because we deserve a really lush cultural landscape. There’s so much danger in the idea of one story.”

In the case of “Waitress,” the story is distinctly feminine — and remarkably dark despite its sweet, pop-driven edges, Bareilles says.

Based on the 2007 indie film written by Adrienne Shelly, the musical trains a spotlight on a waitress named Jenna who accidentally gets pregnant by her abusive husband, Earl. She cheats on him with her married gynecologist, Jim. Ultimately, winning a pie contest, with its attendant reward money, becomes her obsession and imagined way out.

That this story has an audience — and not a small one — is changing the minds of Broadway’s biggest producers, says Laura Penn, executive director of the Stage Directors and Choreographers Society, a union representing those fields in theaters across the country.

Producers, she says, are returning to people like Shapiro, MacKinnon and Marianne Elliott, the two-time Tony-winning director of “War Horse” and “The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time” who was nominated again this year for “Angels in America.”

“Women are beginning to establish themselves as folks you can go back to, and they will deliver. Plus, the women who are working consistently on Broadway are taking their access seriously and trying to make sure that women are represented across the creative teams.”

Leigh Silverman, who was nominated for a Tony for directing “Violet” in 2014, has staffed her upcoming Broadway play “The Lifespan of a Fact,” starring Daniel Radcliffe, Cherry Jones and Bobby Cannavale, with what is believed to be Broadway’s first all-female design team: scenic designer (and MacArthur genius) Mimi Lien, costume designer Linda Cho, lighting designer Jen Schriever, sound designer Palmer Hefferan and projection designer Lucy Mackinnon.

Another notable success for women in theater came this summer when — for the first time in its 57-year history— the Public Theater’s Shakespeare in the Park featured a show (“Othello”) in which four core design roles were filled by women.

“It’s incredibly satisfying and long overdue,” Penn says of such achievements. “And it shouldn’t be something we’re so excited about.”

According to the statistics kept by the Stage Directors and Choreographers Society, the number of women on Broadway claiming the titles of director or choreographer have been somewhat stagnant. In the 2015-16 season, 11 of 53 contracts went to women; in 2016-17 that number was 12 of 66; in 2017-18, it was eight of 46.

A simple search for female directors on the Broadway League’s Internet Broadway Database will yield 505 names, versus the 2,897 that appear when you run the same search for men.

The League of Professional Theater Women produced a 2015 study, “Women Count: Women Hired Off-Broadway 2010-2015,” which found that female playwrights represented about 30% of all plays produced over those five seasons and that women made up about 33% of the directors for the same time period.

One of the things that women in theater tend to emphasize is that they will have achieved their goals when they are no longer thought of as “women in theater.” Or as Bareilles puts it, “when we can drop the qualifiers.” She hopes that her work can speak to young girls in a way that encourages a sense of ownership over their own power, not necessarily from the perspective of, “I’m a girl fill-in-the-blank,” but rather of, “I’m a creator, I’m a writer, I’m a lyricist, I’m a choreographer.”

Lisa Peterson, who is directing the upcoming production of Lynn Nottage’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play “Sweat” for Center Theatre Group at the Mark Taper Forum, has similar feelings. She didn’t always identify as a female director early in her career, although she has recently seen the value in that.

“I think it’s probably still difficult for young women to convince producers that they have the kind of natural authority that people associate with a director,” she says, adding that she believes the industry is, indeed, chipping away at the problem.

For her part, she doesn’t perceive a difference working with a female writer like Nottage versus a male writer, even though that kind of pairing is still quite rare.

“What I’m thinking about is Lynn’s skill, Lynn’s success, and I’m not thinking about it from a gender point of view,” she says. “I’m thinking about it from an experience point of view.”

That point of view — the one that rewards professionalism — is what women hope will come to dominate as they increasingly make their presence known backstage and at the box office.

“My takeaway was that there was great excitement, and almost a sense of relief, to see women being offered these roles,” Bareilles says of “Waitress.” “And the most exciting thing is looking at the next generation of composers, book writers, directors and choreographers now that there’s this wonderful network of women in the industry.”

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

‘Waitress’

Where: Hollywood Pantages Theatre, 6233 Hollywood Blvd, L.A.

When: 8 p.m. Tuesdays-Fridays, 2 p.m. and 8 p.m. Saturdays, 1 p.m. and 6:30 p.m. Sundays; ends Aug. 26

Tickets: Starting at $49

Info: (800) 982-2787, www.hollywoodpantages.com

ALSO:

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.