‘We get people to stop and look’: The election year’s most provocative political artists

In the absence of election-year artwork as ubiquitous as Shepard Fairey’s 2008 “Hope” poster, political memes have become dominant images this political season. But that doesn’t mean the art world has been silent.

Activist street artists have been especially busy creating some of the presidential campaign’s most provocative political statements. Their bold approach inherits a long tradition.

“We’re not talking about sanctioned public art,” says veteran L.A. art agitator Robbie Conal. His posters depicting Donald Trump framed by the words “Bully Culprit” have been pasted all over the city. “In my case, it’s a minor form of civil disobedience.”

Conal gained popularity in the 1980s for his anti-Reagan “Contra Diction” posters and other responses to the Iran-Contra affair. But while Republican lawmakers have been the subjects of some of his most striking images, he’s targeted Democrats as well. One of his most memorable posters was an image of Bill Clinton juxtaposed with the words “Dough Nation.”

For this election, Conal says, "with Trump, there’s no way I couldn’t do anything.”

At 72, the artist continues to lead an army of volunteers that placards Los Angeles streets with his anti-Trump posters.

“Thousands and thousands of people see the posters whether they are looking for them or not,” Conal says. “That's a level of engagement in a much more public sphere than a clean white box — an art gallery or a museum.”

Artist Daniel Gonzalez, who made a series of “Viva Bernie!” signs earlier this year in his Highland Park print shop, credits Conal’s early Reagan posters as one of his main career inspirations.

“We bother the status quo,” Gonzalez says of street artists. “We get people to stop and look.”

It’s not only liberal artists who are trying to shake things up with political images. Republican artists are harder to find, but L.A.-based graphic artist SABO has gotten attention by waging a poster campaign against what he calls the “leftist” establishment.

“After George W. Bush was elected, I couldn’t turn around anywhere and not hear someone define me for being a Republican … for being a racist, being a homophobe, being rich,” says SABO. “But I’m none of those things. I noticed there were no artists pleading my case or standing up for me as a Republican. And I kind of figured, screw it, I’ll do it.”

One of SABO’s recent stunts targeted the “Refugee” exhibit at the Annenberg Space for Photography in Century City. The artist manipulated bus stop posters promoting the exhibit by substituting the original photographs with images of the Islamic State fighters.

“I don’t think my work is meant to offend,” SABO says. “I think I challenge people to such a degree that maybe I scare them.”

For many artists, it’s Trump’s stances on immigration and national security that have spurred them to address the public directly.

The artist known as Plastic Jesus responded to Trump’s pledge to build a wall between Mexico and the U.S. by constructing a miniature wall around the Republican candidate’s Hollywood Walk of Fame star. Plastic Jesus is also responsible for the “No Trump Anytime” parking signs that have cropped up in Los Angeles and other cities across the country.

“I have become more and more frustrated with the mainstream media ignoring issues that really affect most people,” the artist says.

INDECLINE, an underground collective of anonymous artists, feels a similar compulsion to speak directly to the public.

“We want to redirect attention,” says an INDECLINE spokesperson who would not give his name.

The group brings a punk-rock ethos to ambitious street installations that are filmed and disseminated on social media to ensure their messages last beyond the art’s removal. Last summer, after Trump made comments about Mexico sending “rapists” to the U.S., members of the group traveled to Tijuana to paint a mural that said “Rape Trump” on the wall separating the U.S.-Mexico border. And in California’s Mojave Desert, the group created what it claims is the “largest illegal graffiti piece in the world” by painting the words “This Land Was Our Land,” visible from the air, on an old runway.

The INDECLINE piece that’s gotten the biggest attention by far, however, is the group’s life-sized naked Trump statues, which were unveiled simultaneously in Los Angeles, San Francisco, Cleveland, Seattle and New York on Aug. 18. The statues were quickly taken down by city workers in each location, but not before generating a social media storm.

“We end up hijacking the media by getting our own stories put out based on our work,” the INDECLINE spokesperson says of the group’s actions.

Painters, cartoonists and multimedia fine artists may not receive the same levels of viral attention as street artists, but many are using their work to voice their election concerns.

“It seems as though many more people have the compulsion to make art about this presidential primary and election season than I saw in 2012 and 2008 and 2004,” says artist Dan Mills, whose digital-montage pieces satirized the unconventional turns of the GOP primary race.

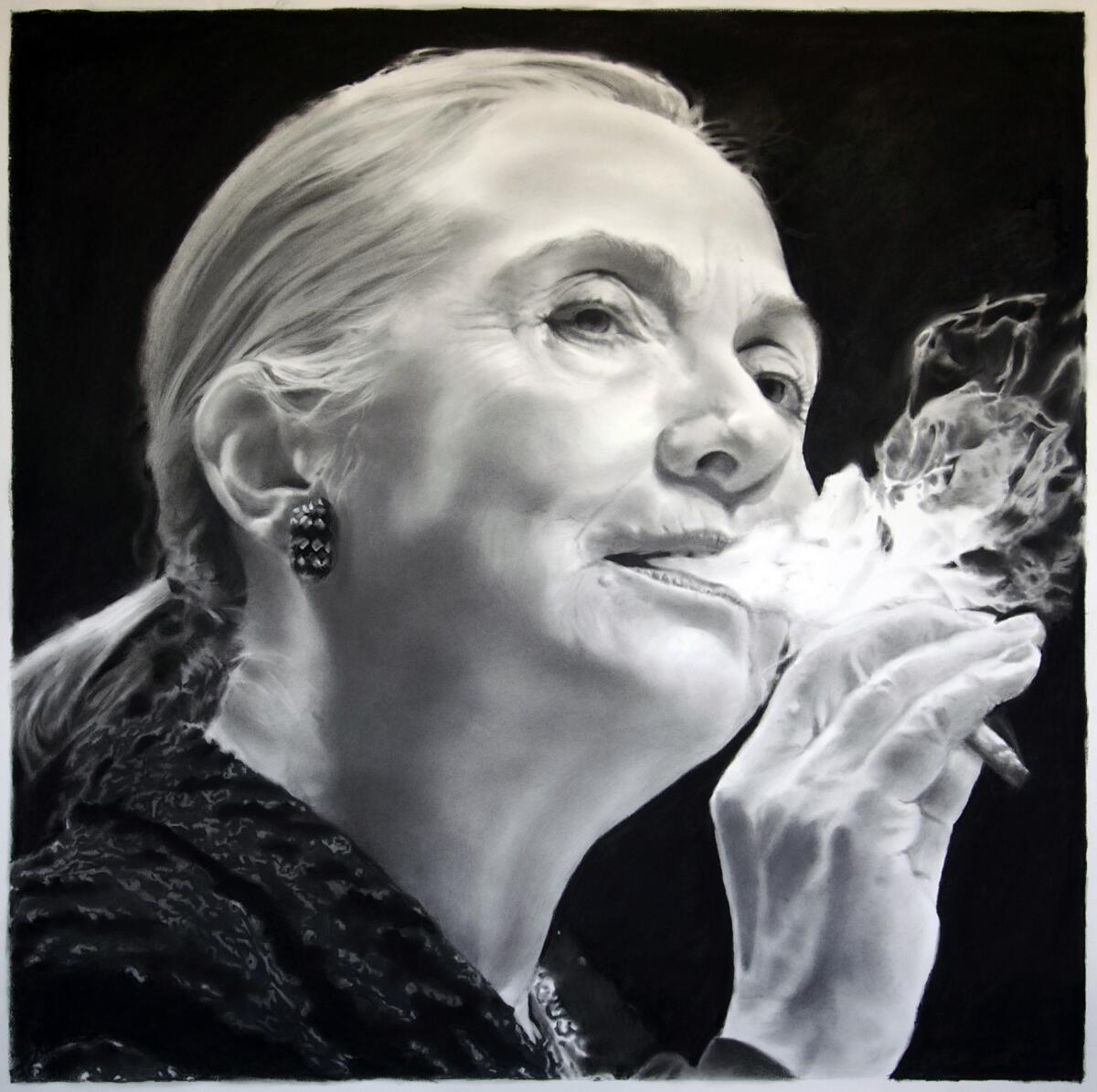

Los Angeles artist Eric Yahnker, who told Paper magazine that he turned to art “after I got kicked out of USC journalism school for majoring in partying,” calls himself a “glorified political cartoonist.” But his meticulous pencil drawings of political and pop culture figures — including Hillary Clinton smoking a cigarette, Trump wearing earrings, Gollum from “Lord of the Rings” in a “Make America Great Again” hat — have been seen in galleries and social media platforms around the world.

Artist Deborah Kass, whose work is shown internationally, made a commemorative print for Clinton (offered by the campaign as a fundraiser) with the message “Vote Hillary” under an image of a scowling Trump.

“It's based on Andy Warhol’s ‘Vote McGovern’ piece from 1972,” Kass says. “It’s actually a piece I wanted to make for Bush, but this seemed like a better time to do it.”

Like Fairey’s “Hope” poster, the Warhol print has been used as a template by numerous artists. Gallerist and artist Robert Berman, of his eponymous gallery in Santa Monica, has made a series of election-year works based on “Vote McGovern” (which curator Helen Molesworth has put on view this election season at L.A.’s Museum of Contemporary Art). In 2008, he used an image of George W. Bush for a “Vote Obama” print in collaboration with artist John Colao; in 2012, Berman chose to depict Mitt Romney’s dog Seamus for his second “Vote Obama.” This year, like Kass, Berman chose a Trump image, but the “Hillary” in “Vote Hillary” is written above a crossed-out “Bernie.”

David Gleeson, who with Mary Mihelic forms the art duo called t.Rutt, cites the late dissident and Czech President Vaclev Havel as part of his inspiration for purchasing the first campaign bus used by Trump for a traveling performance art series in which he and Mihelic interact with voters.

“He said if we are to change our worldview, images must change,” Gleeson says of Havel. “Artists have a very important job to do. They’re not just out there entertaining rich people. They really matter.”

“I don’t pretend for one minute that my work will change anything or much at all in society,” says Plastic Jesus. “But if I can change one person’s opinion or even consider other ways of looking at the issues in the news, then I’ve done my job.”

This story is based on a project reported and produced by USC Annenberg School of Journalism graduate students Hannah Deitch, Stefanie De Leon Tzic Brian Marks and Ethan Varian. The story was written by Deitch. View the original project here.

Sign up for our weekly Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

ALSO

Call it the LOLcat effect: Memes are the digital folklore of the 2016 election

How Shepard Fairey's arrest provides a new look at an old question: Is it art or is it vandalism?

Spray-paint revolution: The ‘OutsideIn’ exhibition and how street art has bled into pop culture

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.