George Takei is giving 70 years of his belongings to a museum. Here’s a sneak peek

George Takei is giving 70 years of his belongings to a museum. Here he gives a sneak peek.

Laid bare on a conference room table at the Japanese American National Museum is a map of George Takei’s life. It’s not composed of craggy lines or river bends but of loose objects, as if Takei had dumped the contents of his garage onto the oblong table. Old family photographs, yellowed television scripts, threadbare costumes, family heirloom art works, handwritten letters — each item is a portal into a distinctly different Takei world.

“Let’s see, what’s here?” Takei says in that familiar, deep baritone as he orbits the table. “Oh, this — I used this staff to climb Mt. Fuji! And this photograph — I was a member of the Boy Scouts, and I played bass bugle.”

A scribbled letter from director Francis Ford Coppola, who Takei says still owes him $500 from when they were students at UCLA, sparks a deep, melodious guffaw: “Bwahahaha. Maybe one day,” he jokes.

The actor and activist, best known for his role as the Starship Enterprise’s Hikaru Sulu on the original “Star Trek,” has donated his collection of personal ephemera to the museum, which will present the exhibition “New Frontiers: The Many Worlds of George Takei” in March. It’s the first in a series of exhibits the museum will stage dealing with stereotypes of Asians and Asian Americans in the media, and Takei has agreed to give The Times an early guided tour inside some of the 300 linear feet of banker’s boxes that he donated.

Very few people have traversed as many worlds as George, both narratively in his career onscreen and literally in his life on Earth as George Takei.

— Jeff Yang, exhibition curator

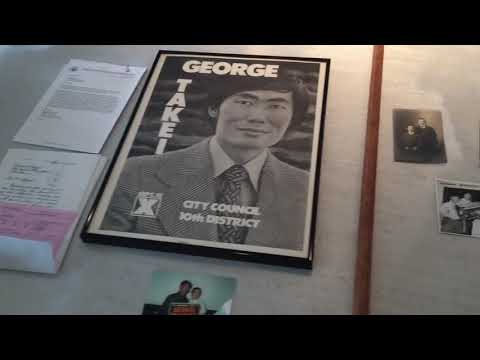

At 79, Takei has had a particularly multifaceted life and career. So circling the table with him is like traversing a galaxy of experiences — from his childhood imprisonment in Japanese American internment camps to his 1973 ambitions running for Los Angeles City Council, his 29-year partnership with now-husband Brad Takei and, most recently, his fervent, online political activism. As Takei navigates this nostalgic terrain, his emotions shift, like micro-climates, object to object.

A black and white photograph of his mother’s family in the rural Sacramento farming community where they lived stirs pride: “My grandmother was quite the dynamo,” Takei says.

Hand-carved Japanese festival masks bring on pensiveness: “I’m an actor, so I’m interested in theatrical faces, I suppose, always have been.”

Nearly every object connected to Takei’s father, who immigrated to the U.S. from Japan as a child and who became a leader in L.A.’s Japanese American community, causes his eyes to well with tears. “Yeees,” Takei says, “he was a special guy.”

It was the most egregious violation of the United States Constitution.

— George Takei

Takei’s donation — intimate objects never before displayed publicly — is the museum’s largest collection centered on any one individual, but it’s more than just a window into the actor’s personal history. The artifacts and anecdotes, spanning more than 70 years, also are meant to show how America’s broader political and cultural landscapes have morphed over the decades.

“Very few people have traversed as many worlds as George, both narratively in his career onscreen and literally in his life on Earth as George Takei,” says exhibition curator Jeff Yang. “He came out of one of America’s darkest chapters during World War II and went through the transformation that occurred in Hollywood with the rise of television and the emergence of a multicultural palette of stories and performers. He was the face of marriage equality and has become a social-media influencer. There’s no one else who shares that kind of varied story.”

For Takei, the exhibition puts a fine point on his life’s work: educating the public about the Japanese American experience, especially the internment camps.

“The internment is our big historic story,” Takei says, adding that media stereotypes of Japanese Americans as inscrutable or ominous servants at the time “fed into the hysteria and fear,” making that chapter of American history possible. “It was the most egregious violation of the United States Constitution. And it was facilitated by the fact that there were these preconceived images and conceptions of Japanese Americans. So I’ve been advocating for an exhibit that examines that history.”

To characterize a whole faith group as one kind is what happened to us during the Second World War. It’s dangerous and un-American.

— George Takei

It’s a message that is particularly important given the recent election cycle, says Takei, who has turned to his nearly 10 million Facebook “likes” and 1.8 million Twitter followers to express his fierce criticism of Donald Trump.

“Muslims are 1 billion people in this world, yet to infer they’re all potential terrorists is outrageous,” Takei says. “To characterize a whole faith group as one kind is what happened to us during the Second World War. It’s dangerous and un-American.”

An abstract wood sculpture on the table brings Takei to a complete stop. Takei’s father made it by boiling and polishing a bayou swamp root while the family was imprisoned at Rohwer War Relocation Center in Arkansas. Takei lived behind the barbed wire fences of internment camps in Arkansas and Northern California from age 5 to 9. The sculpture, he says, shows his father’s creativity and resilience amid adversity. “This, to me, represents my father’s artwork,” he says. But Takei’s eyes, glassy with tears, quickly turn angry when explaining the family’s relocation to L.A. after being released.

“We lived on skid row in downtown Los Angeles and that, to us, was terrifying,” Takei says. “The stench of urine everywhere.”

Then, as if at warp speed, the anger dissipates and there is laughter again, prompted by a taupe safari hat.

“And this hat?!” Takei says, eyeing it quizzically.

“That’s from ‘I’m a Celebrity ... Get Me Out of Here!’ — a British reality TV show,” says Brad Takei, who’s politely watching this tour de force of memorabilia from the sidelines. “You came in second.”

“Oh, right, you live in the jungle of Australia for a month and that’s what I wore!” Takei says, laughing.

Takei is something of a “natural collector,” his husband says. Shortly after the couple had been dating, he began archiving Takei’s belongings, carefully boxing incoming items, such as fan art and publicity shots from guest spots on “The Simpsons” and other TV shows, storing it all in the couple’s Hancock Park garage. The Japanese American National Museum, at which Takei has been a board member for nearly 30 years, took most everything Takei offered.

“It was either that, or rent a storage locker someplace,” Brad Takei jokes.

“Bwahahaha!” Takei bellows.

A photograph of one of Takei’s early theatrical heroes, British actor Alec Guinness in the 1961 film “A Majority of One,” sobers him. The Caucasian Guinness plays a Japanese businessman, with thick pancake makeup smeared on his face and rubber folds on his eyelids. “It’s scary. He looks reptilian to me!” Takei says.

Takei was intent on busting media stereotypes of Asians, even as a teenager. When his father tried to dissuade him from becoming an actor, warning, “Look at the TV, look at Broadway theater, what kind of images do you see?” Takei responded: “I’ll change it, Daddy!” And he did.

Front and center on the table is Mr. Sulu’s maroon and black uniform from the film “Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country.” Takei says that for years he pushed writers, producers and “Star Trek” creator Gene Roddenberry, throughout both the TV series and films, to make Sulu a captain.

“Because the Star Fleet is supposed to be a meritocracy,” Takei says. “And yet, promotion after promotion, there I am at that helm console, saying: ‘Aye, sir, warp 3.’” Finally, with “Star Trek VI,” Takei says, “there’s a brand new captain, Sulu, there in the center seat!”

A photo album of the Takei’s wedding — held at the museum with a Mexican American Buddhist minister — embodies another of the actor’s passions, advocating for diversity, marriage equality and LGBT rights. The couple, who married in 2008, boasts the first same-sex marriage license issued by the city of West Hollywood.

Fearing repercussions in Hollywood, the Takeis had been a closeted couple. The actor came out publicly at age 68, prompted by Arnold Schwarzenegger’s veto of same-sex marriage legislation in 2005. Takei gave his first interview as an openly gay man that year to Frontiers magazine, a copy of which will be on display in the forthcoming exhibition.

“He thought Hollywood would be finished with him because he’d be too controversial to cast,” Brad Takei says. “And George, what happened?”

“My career blossomed,” Takei says victoriously.

“It was a tenor of the times,” Brad Takei says. “Turns out America likes an authentic voice.”

The museum collection will be a living, breathing one, with Takei donating new items on a rolling basis. That may soon include the script of the revival of Stephen Sondheim’s musical “Pacific Overtures,” set to open next spring off-Broadway with Takei in the lead role.

Seeing so much of his life splayed out on the table is a bit overwhelming, Takei admits, surveying the room. A new emotion sweeps across his face, one even he can’t sum up in single word.

“It’s a mélange of feelings,” Takei says, “some of it is puzzlement — who is that or what was that event? — but there’s also nostalgia, fondness.”

Then the perfect catchphrase comes to mind, delivered in that signature, inimitable tone.

“I guess you could say it’s an ‘Oh, my’ moment,” Takei says. “Oh, myyyyyy!”

Follow me on Twitter: @debvankin

ALSO

Actor-activist George Takei takes command in cyberspace and beyond

How George Takei’s East L.A. boyhood made him take on Donald Trump — in Spanish

George Takei says the decision to make Sulu gay is ‘really unfortunate’

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.