Why is a master of Shakespeare directing the musical ‘Frozen’? Because ‘Let It Go’ isn’t too far from the Bard

Reporting from New York — “We’re standing on the same stage where ‘Oklahoma!’ premiered,” says British director Michael Grandage, gesturing at the flooring beneath his feet inside the historic St. James Theatre on West 44th Street. “‘Gertrude Lawrence and Yul Brynner did ‘The King and I’ on this stage.”

Grandage pauses for a moment, thinking about what he has just said. He glances out at the house with its golden ceiling and 1,710 bright red seats, which will soon be filled with “Frozen” ticket-holders.

“Now we’re about to go on, what will that feel like? What will it be like?” Grandage asks. “I mean, I’m going gray. You can’t think about it.”

To flop with material as pathologically beloved as the 2013 movie “Frozen,” which went on to win an Oscar for best animated feature and to become the highest-grossing animated film of all time, would be more than egg on the face. It would be a cream-pie facial.

Everything that happens in this piece happens in those beautiful, relatively short, five-act pastoral comedies like ‘Twelfth Night’ and ‘As You Like It.’

— “Frozen,” the musical director, Michael Grandage

Happily, Grandage refuses to fret about the pressure. On this abnormally sunny and warm winter’s afternoon, he appears downright relaxed while walking around backstage, pointing out the tiny green bike that Young Anna rides in Act I and talking about how the snow on the roof of Oaken’s Trading Post is inflatable to save room in the theater’s cramped wings.

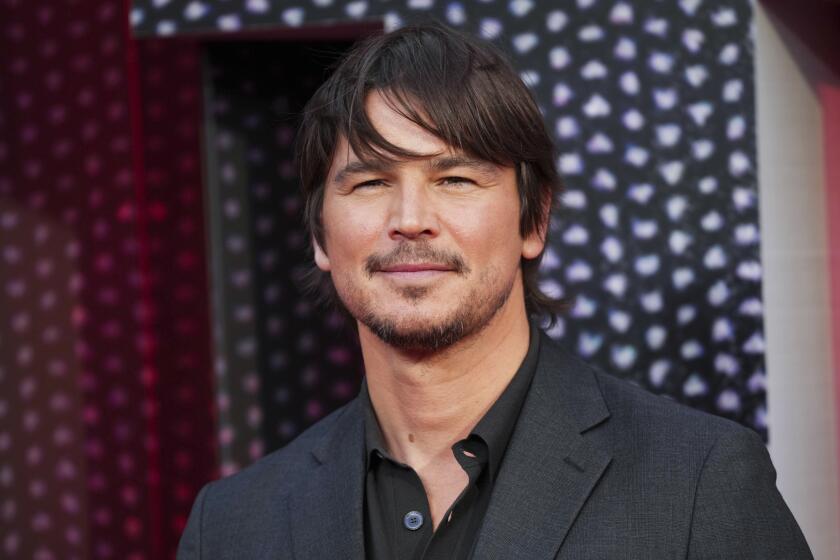

More than a few heads were turned when Disney announced in fall 2016 that it had chosen as its “Frozen” director not a veteran of Broadway musicals but one of Britain’s most prolific interpreters of Shakespeare. Grandage, known for his skill at parsing the taut drama and raucous comedy of the Bard, would be directing a live-action version of a movie that single-handedly revived the market for pretty princess dresses.

Grandage’s 2010 Broadway production of John Logan’s “Red” did win six Tonys, including awards for director and play. He also led New York productions of “The Cripple of Inishmaan” and “Evita,” but “Frozen” is his first original musical.

Where others saw a question mark, Grandage spotted an opportunity. He viewed the Hans Christian Andersen-based fairy tale — about two sisters trapped in a kingdom imperiled by perpetual winter thanks to a crucial lack of communication — as “completely Shakespearean.”

“Everything that happens in this piece happens in those beautiful, relatively short, five-act pastoral comedies like ‘Twelfth Night’ and ‘As You Like It,’ ” he says, reclining in a seat toward the front of the auditorium.

Dressed in black with close-cropped, salt-and-pepper hair, his voice intense and theatrical, he leans into his words as he talks, as if trying to keep up with this own racing thoughts. He laughs easily, but he doesn’t come at his work lightly. Not even if the work is a Disney musical.

It’s important for a director to approach material, no matter how timeworn, as if it has never been staged before, he says.

“ ‘Twelfth Night’ was a new play once. ‘Hamlet’ was a new play. There was a moment in the history of the world when that play was being done before an audience for the first time ever, and nobody knew what was coming next,” he says. “You have to come at it as if you’re telling the story fresh, because if you don’t, you’ll start to direct in shorthand.”

The philosophy informed his approach to the show’s most famous song, that epic ballad of female empowerment. “Let It Go” was a bona fide pop culture phenomenon when the movie came out, one that inspired singalongs at Royal Albert Hall and sparked a whole genre of think pieces dissecting its siren-like draw.

In the film the tune is sung by Idina Menzel, but in the musical, it’s belted out with proud ferocity by the icy-blond actress Caissie Levy in a sequence that includes one of the lavish production’s most eye-popping costume changes.

Whereas some directors might have focused on getting an actress to squeeze every last drop of melodic power out of the notes, Grandage was more interested in mining the lyrics in search of character development.

“We went through, beat by beat and word by word, and found a through-line emotionally and intellectually,” says Grandage, squinting his brown eyes in concentration. “In letting it go, she can narratively take us … to a place where we watch a woman who has been disabled quite seriously by her own powers transform into a woman who is using them to free herself and her imagination in order to understand who she is.”

This type of communication with a director is not as common as one might think, says Levy, who has performed in a number of Broadway shows, including “Les Misérables,” “Wicked” and “Hair.”

“Michael’s whole thing is about finding truth,” she says. “He wants to hear from us. He always has time to sit down and talk about it.”

That’s a sentiment echoed by Levy’s costar, Patti Murin, who plays Elsa’s sister and comedic foil, Anna.

“I don’t think I’ve felt like more of an actor in my career,” Murin says. “He just has this way of pulling things out of you. It’s not that you didn’t know you could do it. You just haven’t had a chance to do it yet, or someone hasn’t dug that deep into your skill set to allow you to do it.”

Irrelevance is the bugaboo that drives Grandage’s contextual deep dives. If a production is not relevant — politically, socially, intellectually, philosophically — if it does not speak to the times we are living in, then it becomes what Grandage calls “museum theater.”

“That’s where the criticism of theater comes into play, and I’ll be the first to support it,” he says. “Even old stories can be given a new interpretation that contributes to the now, or helps form the now, or creates a zeitgeist.”

He stops to catch his breath, rocking forward in his seat and beating his hand on the table to mark each subsequent word: “I think theater at its best can do all of that. I am passionate that theater can quite literally change the world.”

Can “Frozen” do all of that?

Grandage is sanguine.

“It’s been a year and a half, and I’m feeling that we’re representing the best of ourselves,” he says of a process that included a run at the Buell Theatre in Denver in late summer followed by five months of prep work for the Broadway production. During that period, about 30% of the show was changed for clarity and emotional impact.

“Michael had all this pressure on him to bring his theatrical vocabulary to this thing we knew really well in our heads,” recalls songwriter Kristen Anderson-Lopez. “Denver was about giving him and Rob [choreographer Rob Ashford] space to have a first draft.”

That space was an unusual luxury for Grandage, whose team emerged with a new beginning and a new ending, having silenced most of the questioning voices in their heads.

When the show catapults out of previews into opening night March 22, Grandage is indeed prepared to let it go. His focus will be his next project, Martin McDonagh’s “The Lieutenant of Inishmore,” opening in summer in London.

He admits that in the past, shows that he thought likely to succeed have failed, and vice versa. It happens to everyone, even Disney, he says.

“What we all learn to do is just get the show up, see how it is, see how it reacts with an audience, see if there’s good word of mouth, see if the message spreads, and then you’ve either got something that will live on, or you’ve got something that will last a natural course and just come to an end,” he says. “And we don’t know what we’ve got yet, and we won’t know until we get it up.”

ALSO:

Zooey, Taye, Rebel: Cast for Hollywood Bowl’s ‘Beauty and the Beast’

Lucas Museum of Narrative Art: New renderings released

Taylor Mac on gay history, ‘Hamilton’ and his 24-hour shows at the Ace

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.