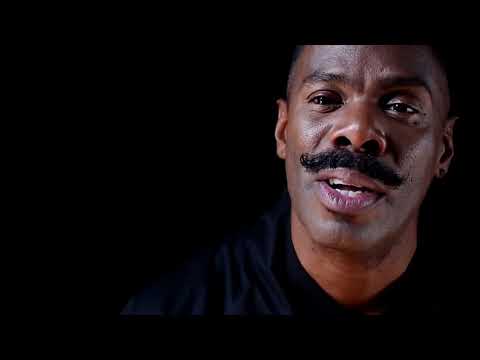

Q&A: The lives of Colman Domingo: acting in ‘Fear the Walking Dead,’ writing ‘Dot,’ now directing ‘Barbecue’ at the Geffen

Actor, director and playwright Colman Domingo talks about directing ‘Barbecue’ at the Geffen Playhouse in Los Angeles.

Colman Domingo has never been busier. A Tony nominee for “The Scottsboro Boys,” the 46-year-old actor is playing the mysterious Victor Strand on TV’s “Fear the Walking Dead” and is prominent in Nate Parker’s film “The Birth of a Nation.”

A playwright as well as actor, Domingo won a Lucille Lortel Award for his 2009 play, “A Boy and His Soul,” and earlier this year got excellent notices for his new dark comedy, “Dot,” an off-Broadway hit about family dynamics and Alzheimer’s directed by Susan Stroman (also a Tony nominee for “The Scottsboro Boys”).

Now Los Angeles audiences can see proof of Domingo’s solid reputation as a director when Robert O’Hara’s play “Barbecue” opens Sept. 14 at the Geffen Playhouse. In town to direct his friend O’Hara’s funny, tough play, Domingo described “Barbecue” as a “searing satire about racial stereotypes, family dynamics and addiction.”

Formidable onstage and onscreen, Domingo was amusing, friendly and thoughtful when he paused for this edited conversation:

What attracted you to directing “Barbecue”?

The first time I read “Barbecue,” I fell in love with it. I never laughed so hard in my life. I was also in its early workshops as an actor, and I knew I was the right director for it. I help as an actor to develop Robert’s work, and he works with me as a dramaturge and director. We worked on my play “Wild With Happy” at Sundance, and he directed the production at the Public Theater in New York. When he called with this offer, I said yes immediately.

Both of you seem drawn to work that pushes boundaries and challenges audiences.

We’re very interested in the way we tell a story. Part of the responsibility of being a modern storyteller is understanding modern audiences and trusting what they can handle. It’s not just settling into what we think they want.

Could you give me an example?

There are certain tropes Robert and I aren’t interested in. We’ve seen the typical mama in African American plays, but have we ever seen a woman like the mother in my play “Dot”? This elegant middle-class woman with a very fine hairdo is political and outspoken and rich and layered and not wailing, “Oh, Jesus, help me.” That is also what a family looks like.

“Barbecue” and “Dot” are plays that are funny and serious.

I think comedy and satire are the strongest ways to deal with very serious themes and very painful themes. We need to be able to learn to laugh at ourselves and at how ridiculous some situations are, whether it’s dealing with a matriarch with Alzheimer’s or a sibling with severe addiction. We go to satire so it can resonate deeper. No one wants to see a pamphlet for healthcare or self-improvement onstage.

I think comedy and satire are the strongest ways to deal with very serious themes and very painful themes.

— Colman Domingo

What led you into theater in the first place?

I grew up in West Philly, and I took an acting class at Temple University there. Then, after school, I moved to San Francisco. I wanted to redefine myself and start my path as an artist. I went on auditions and on my first job as an actor, the director said, “We’re going to start blocking,” and I didn’t know what that was. So I looked it up. I would go home and read books about acting by Uta Hagen and Stanislavski and Meisner. I would also go to rehearsals for shows I wasn’t in, and I’d ask questions of senior actors. I was learning by watching and listening — the old way, like being an apprentice but getting paid for it. For 10 years, San Francisco was my conservatory and where I started to expand into directing and writing.

Now you are a triple threat: actor, director and playwright. How did that happen?

As an actor, I was always looking at both the macro and micro of the work, and I always had comments to make. A director I worked with in San Francisco said since I had so much to say, I should probably say it. That’s when I started taking my hand at writing.

How do the acting, directing and writing all feed one another?

I think it strengthens my focus. In any given week, I’m bouncing back and forth. Today we’re talking about my directing “Barbecue,” and coming up are publicity for “The Birth of a Nation” and “Fear the Walking Dead.” I’m also writing a couple of musicals and a play, and I’m working on a pitch to do a TV series about “Dot.”

So I’m constantly going back and forth, and it keeps me sharp. I know that my work as a director helps me clarify my storytelling. The stories have to be stageable. Actors think a lot of the time about what they need to do as actors on a set or in a play, and I’m always thinking about everyone else’s jobs as well as my own. I can raise questions to the writer. Because I can do all these things, I’m a better collaborator.

You’re also working across mediums — theater, TV and film. How do they all interact?

I started working off-Broadway, then expanded to Broadway. I was a workhorse, and I did shows that didn’t start on Broadway like “Passing Strange” and “Scottsboro Boys.” With my Broadway career came more visibility. People like Spike Lee, who directed me in the film of “Passing Strange,” and Lee Daniels, who directed me in “The Butler,” first saw me onstage. It was the same with Steven Spielberg, who cast me in “Lincoln.”

So much of your work onstage and onscreen both has given you a chance to speak on things you’re passionate about. How do you choose?

I’ll be very honest. It feels as if they choose me. The projects always seem to be a great match. Like “Scottsboro Boys.” When I got that script, where they needed a black actor to be malleable enough to play Caucasian racists in 1931, be satirical, sing and dance, I looked at it and said, “That’s for me.” It means the world to me to speak about the ills of racism in our society. I’m not on anyone’s radar when it comes to fluff.

The most terrifying thing is the fall of society. I always have questions in my own work about mortality, family and survival.

— Colman Domingo

What about “Fear the Walking Dead?”

That’s not fluff! I think it is a commentary on the lengths we will go to survive. I think the show is less about zombies and more about our humanity — or inhumanity. I think it holds a mirror up to who we are when faced with tragedy and disaster, whether it echoes a tsunami, Hurricane Katrina or 9/11. It asks: If something were to happen right now, how do we get to our families? How do we come together to support one another? It’s about that. The most terrifying thing is the fall of society. I always have questions in my own work about mortality, family and survival.

It seems to me that you also have a sense of responsibility about portraying strong black figures like Ralph Abernathy in “Selma” and Nat Turner’s comrade Hark in “The Birth of a Nation.”

Portraying these complicated African American men is extremely important and resonant, especially now. Ever since I started acting and going for auditions, I thought, I’m from the inner city and I don’t want to perpetuate stereotypes of black men. If I ever play a drug dealer, he would be complex, with layers and texture. He wouldn’t be marginalized as some violent, inhumane caricature of an African American man. We don’t have to be saints or sinners, but we have to be complex. It’s very important to me to show people what black men are.

Follow The Times’ arts team @culturemonster.

ALSO

‘True Blood’ star Rutina Wesley embraces blood, sweat and tears of her new show, ‘Queen Sugar’

Amy Adams on ‘Arrival’ and abandoning her ‘harsh critic’

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.