Review: The collateral damage of genius in Boris Eifman’s ‘Rodin’

Of the ballet choreographers making narrative works for major stages, Russian Romantic Boris Eifman is virtually the only one totally in touch with the 21st century.

Look at his two-act, biographical “Rodin,” which came to Segerstrom Center for the Arts on Friday in the first of four performances, and you find the same in-your-face intensity, the same graphic sensuality, the same appetite for special effects (both in his stagecraft and choreographic technique) and the same sense of pervasive darkness that distinguish the newest blockbuster films (good and bad) and hit television dramas (good and bad).

FULL COVERAGE: 2013 Spring arts preview

Yes, yes, the rat-men and wheeler-dealers who currently dominate Anglo-American ballet have works claiming to be new, but they invariably offer audiences a refuge against the present, a conservative, backdated view of ballet that makes them culturally irrelevant.

Eifman, however, outpaces the zeitgeist, and you can argue that his 2005 “Anna Karenina” is infinitely more powerful and even cinematic than Joe Wright’s recent feature film of the same name starring Keira Knightley.

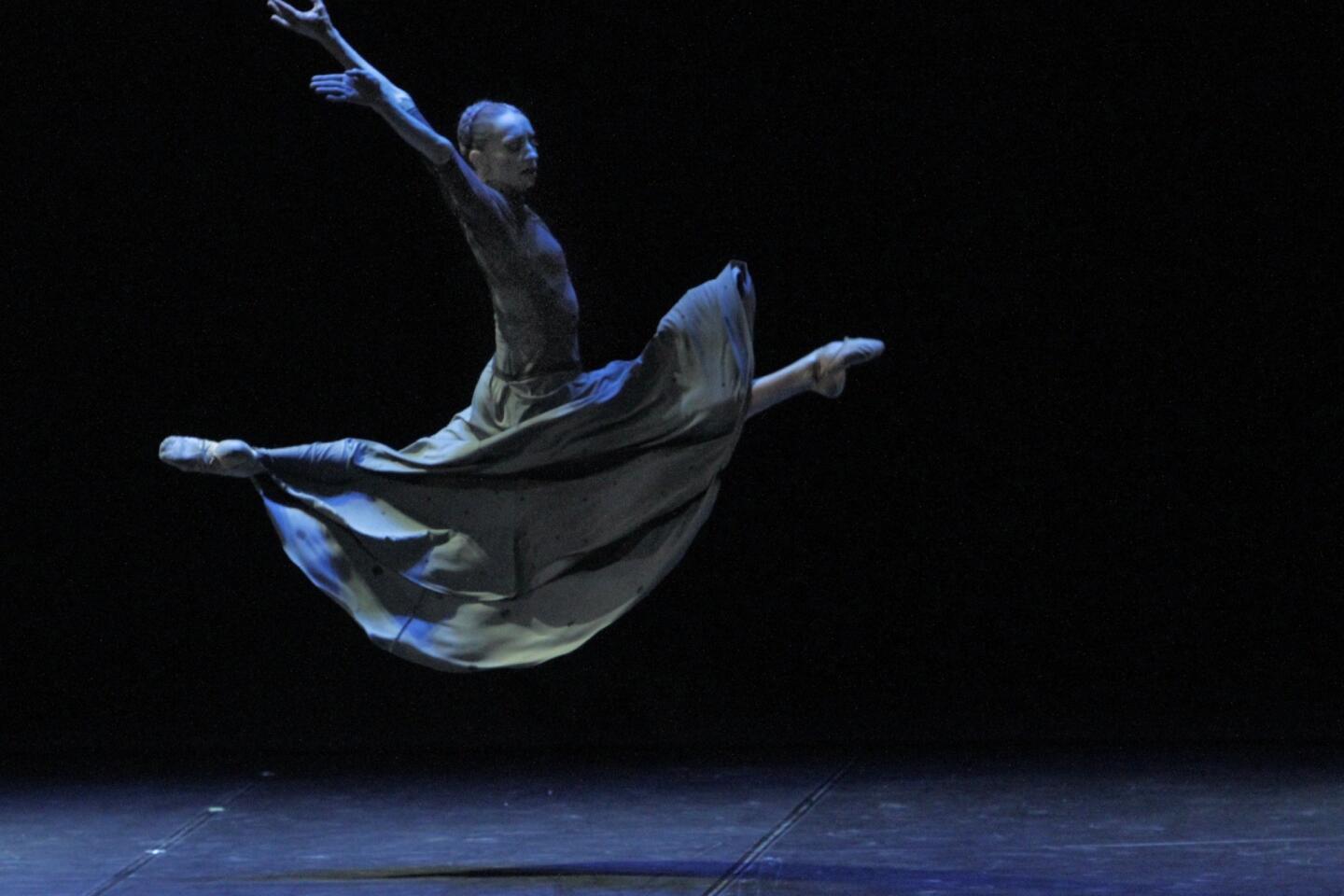

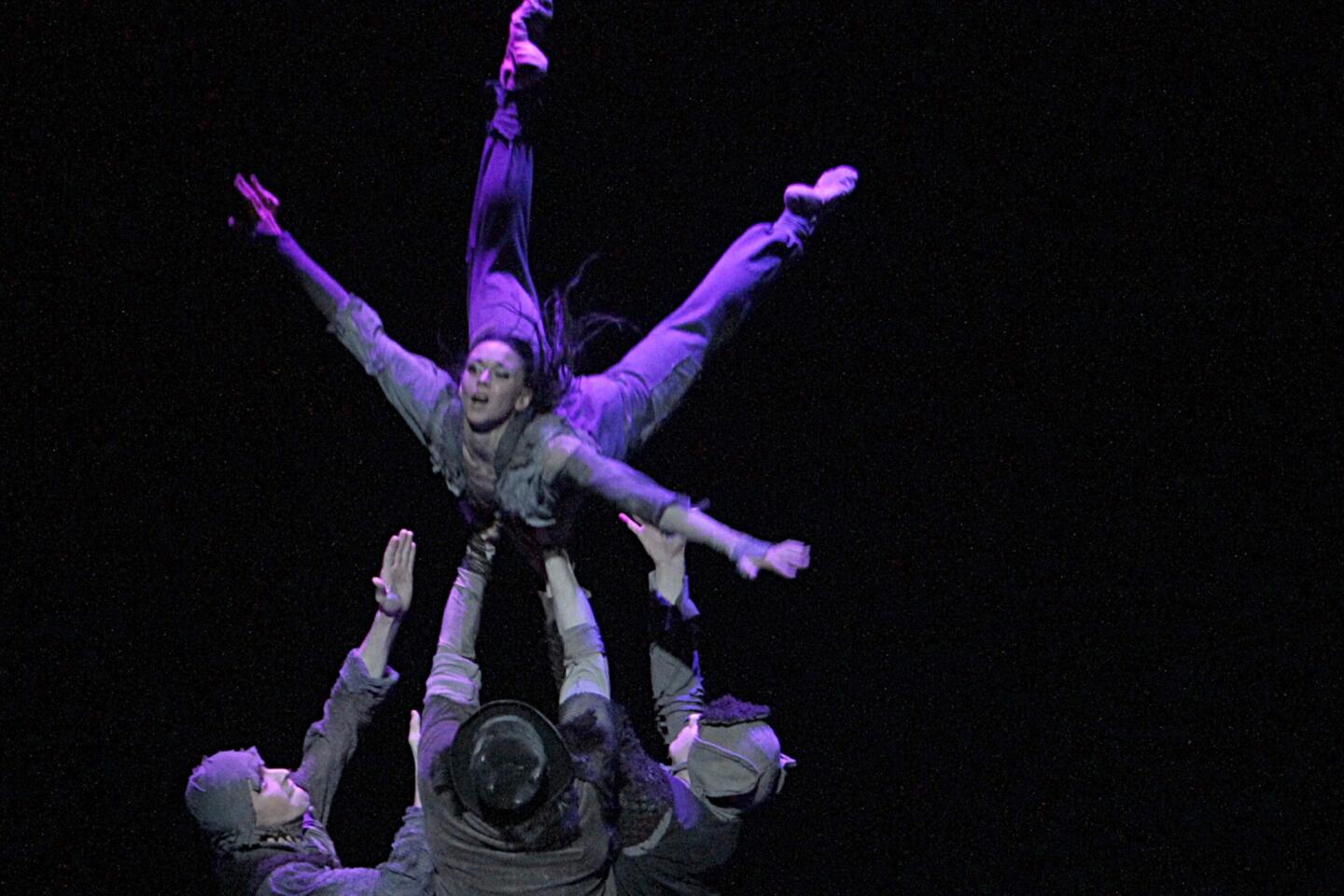

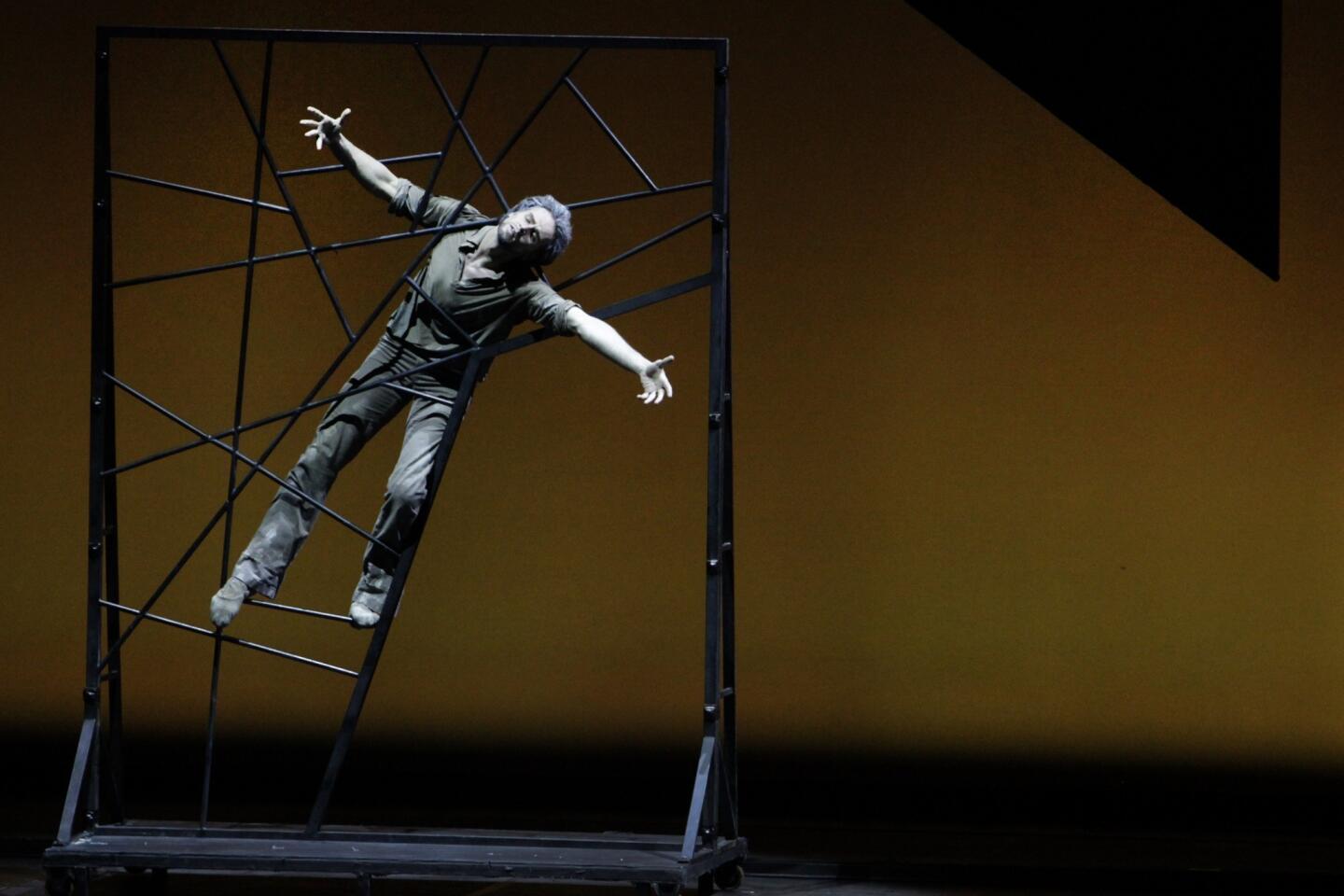

In “Rodin,” Eifman not only depicts the reckless drive of a master sculptor and the two women he destroys but the act of creation itself, using nearly naked dancers as clay to be molded into masterworks.

The ballet begins almost as a parody of the white acts in “Swan Lake,” with Rodin (Oleg Gabyshev) searching for his lover and inspiration, Camille Claudel (Lyubov Andreyeva), among the identically dressed inmates of an asylum. Her thwarted potential as a sculptor is one of the work’s most potent themes, along with the self-sacrifice of Rose Beuret (Nina Zmievets), a less volatile companion.

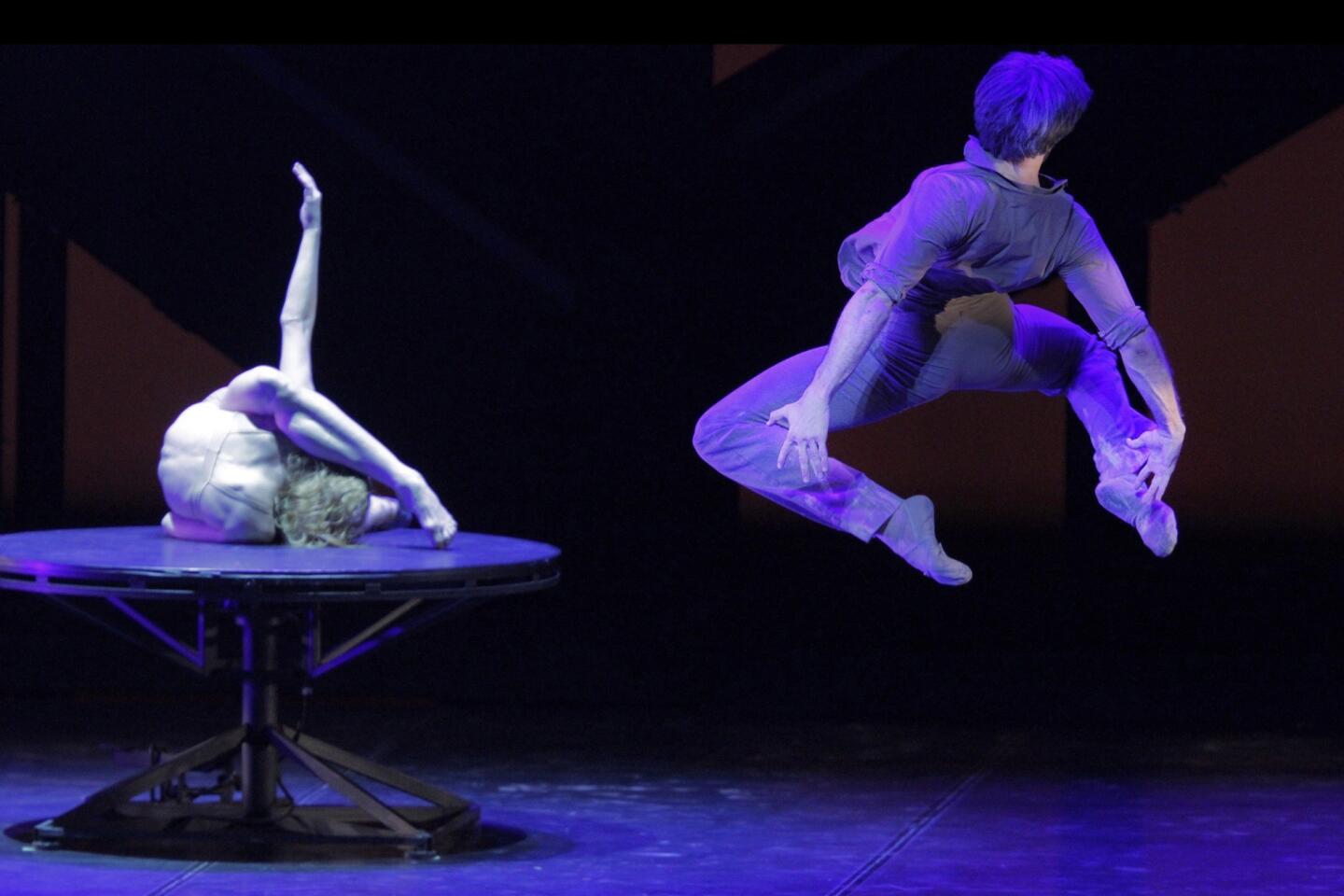

Set to recordings of music from the period plus occasional sonic accents by Eifman himself, the ballet moves fluidly through time, forward and back, using spare, artful scenic motifs designed by Zinoviy Margolin and atmospheric lighting by Eifman and Gleb Filshtinsky.

The sharp-edged asymmetry of the setting is echoed in the splintered movement style, with Rodin given the most conventional sense of balletic flow and Claudel the most daringly spasmodic vocabulary as she descends into insanity.

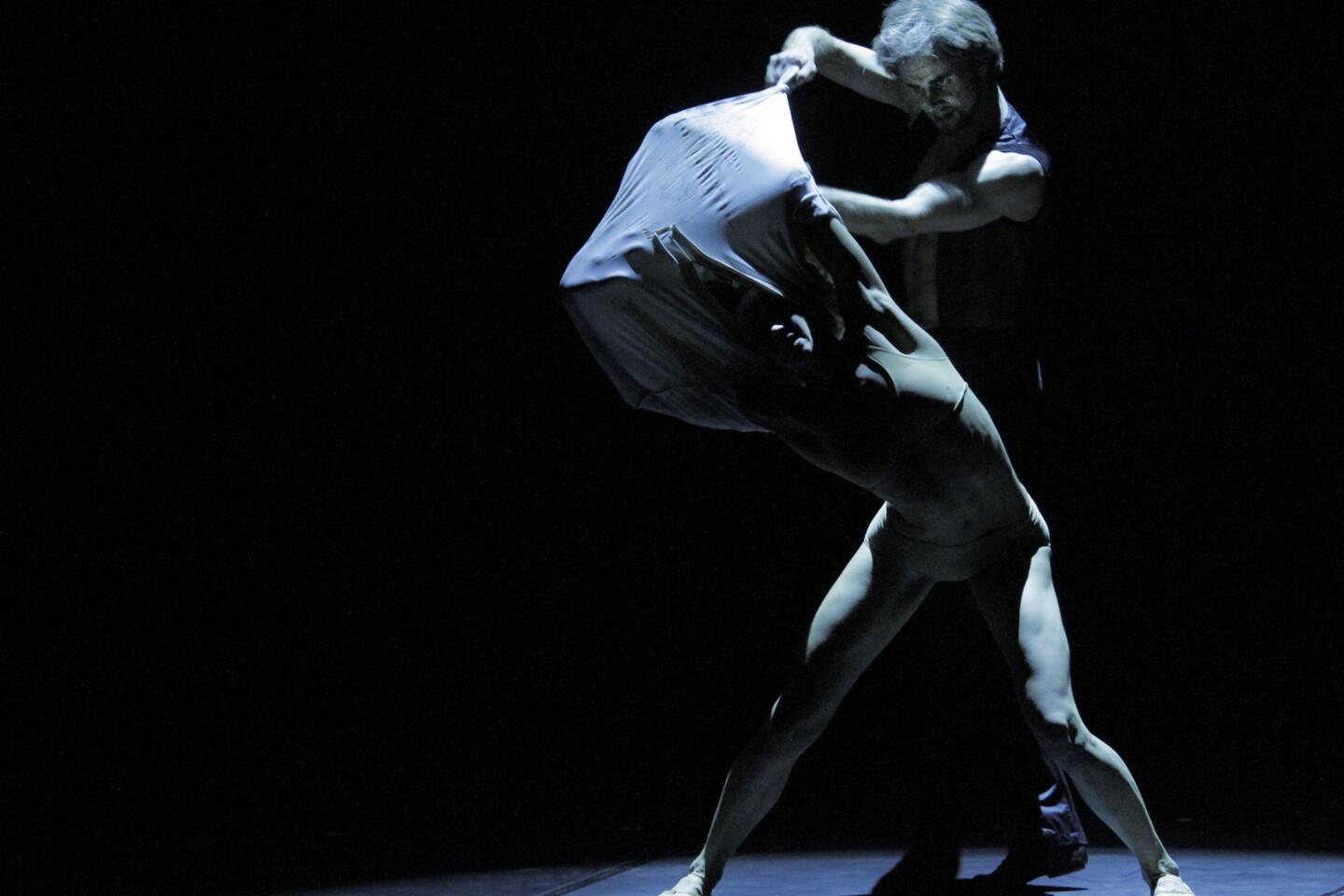

One of the most brilliant sequences begins with a joyless duet between Claudel and someone identified as “a random lover” (Dmitry Fisher), then morphs into an agonizing Rodin-Claudel confrontation and into an even more desperate trio with Beuret. The brief evocations of Rodin’s bronzes (especially “The Gates of Hell”) prove no less masterly.

If Act 1 seems virtually perfect, the second act is padded with splashy, diversionary ensembles: an overlong grape festival and a terrific but expendable can-can.

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures by The Times

Eifman’s large, versatile St. Petersburg company, however, remains faultless.

With his unorthodox bravura highlighted from start to finish, the charismatic Gabyshev is perfectly cast as the embodiment of consuming passion -- for his art and for his women. The tireless Andreyeva contorts magnificently and can break your heart as Claudel propels herself from sustained hallucinations into oblivion. And Zmievets is touching as a helpless witness to multiple calamities.

In “Rodin,” human relationships are shown as the collateral damage of genius, and Eifman’s enigmatic final image -- a body of flesh furiously chopping away at a body of stone -- may be as heroic as some of Rodin’s monumental figures but also might leave us questioning whether those monuments and that genius cost far too much from everyone.

“Rodin,” Segerstrom Center for the Arts, Costa Mesa. 2 p.m. Saturday and Sunday; 7:30 p.m. Sunday. www.scfta.org.

ALSO:

Review: Lang Lang leads the L.A. Phil on a jazzy jaunt

Carole King musical to debut in San Francisco prior to Broadway

MOCA’s ‘A New Sculpturalism’ faces uncertain future without Gehry

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.