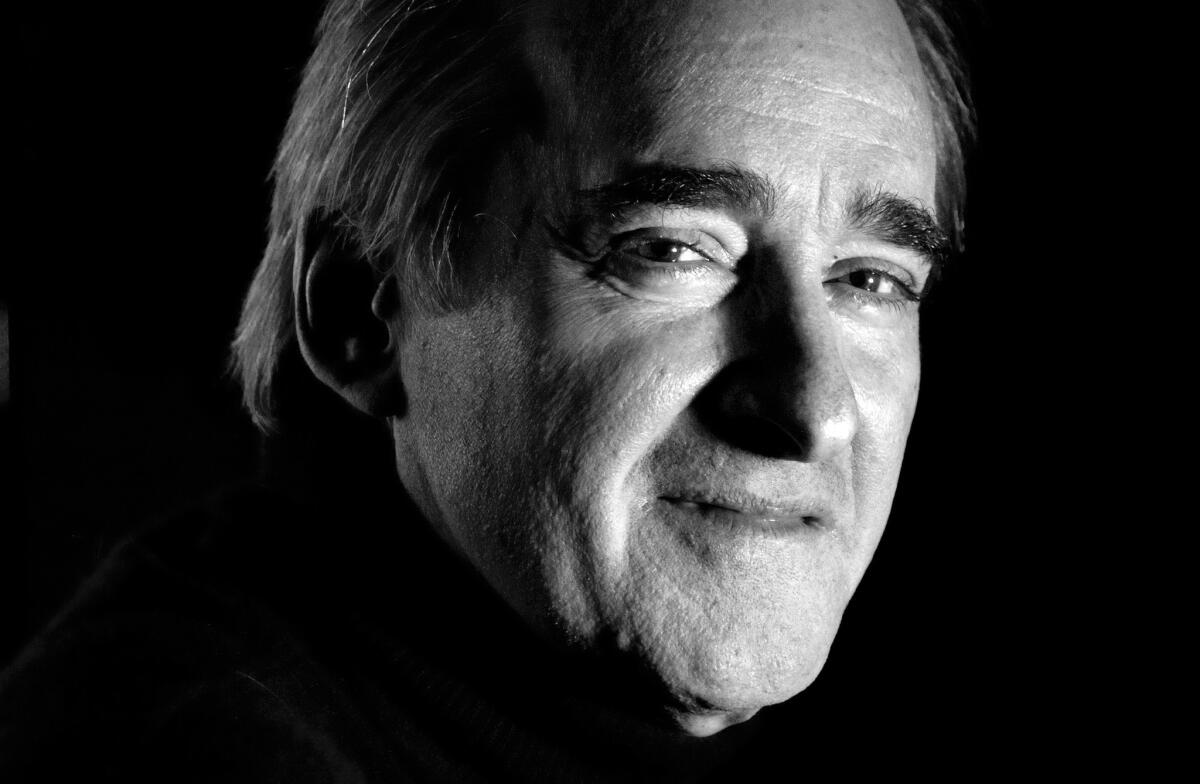

Review: Diverse works given life in Conlon’s ‘Recovered Voices’

Conductor James Conlon is a one-man archaeological dig when it comes to resurrecting long-forgotten composers whose work was suppressed by Nazi Germany.

But in the “Recovered Voices” chamber program he led at the Broad Stage on Thursday, the pieces Conlon chose steered clear of composers whose lives were tragically cut short in the concentration camps.

Instead, the evening focused on five Austrian and German composers whose fates took luckier turns. All of them — Walter Arlen, Hanns Eisler, Erich Wolfgang Korngold, Arnold Schoenberg and Eric Zeisl — escaped the Third Reich and landed in L.A., where they (and dozens of their émigré colleagues) immeasurably enriched the artistic landscape.

CRITICS’ PICKS: What to watch, where to go, what to eat

In performances by students from the Colburn Conservatory of Music and members of L.A. Opera’s Domingo-Colburn-Stein Young Artist Program, the sheer stylistic diversity on display in these scores was striking, from the exuberant 19th century Romantic pastiche in Zeisl’s 1940 horn-quartet, “The Hunt,” played here with burnished tone and nuanced phrasing, to the still-arresting atonality of Schoenberg’s seminal 1911 Six Little Piano Pieces, (which pianist Ory Shihor treated with an airy, almost Debussian delicacy).

Eisler’s wonderful but seldom-heard 1941 piece of mood-painting, “14 Ways to Describe Rain,” employs Schoenberg-like dissonance but to far warmer, more accessible effect. The piece, riveting under Conlon’s baton, was heard together with a screening of Dutch cinematographer Joris Ivens’ experimental short film, “Rain,” which Eisler’s score was designed to be played alongside — more as an oblique musical commentary than a film-score in the traditional sense.

In sharp contrast, the “Five Songs of Love and Yearning” by Arlen, who was present at the concert to hear soprano Tracy Cox’s vibrantly voiced, word-attentive performance of four of the five songs, were composed in 1986 to quasi-erotic religious poems by Saint John of the Cross and communicate in an engagingly American Neo-Romanticism that would sit comfortably beside vocal music by Ned Rorem, Carlisle Floyd or Gian Carlo Menotti. (Arlen is a former music reviewer for the Los Angeles Times.)

GRAPHIC: Highest-earning conductors

And on yet a further stylistic tangent, the String Sextet (1916), written by Korngold as a 17-year-old prodigy, features a restless, often rhapsodic, whirl of melodic ideas, set in opulent harmonic garb reminiscent of Richard Strauss. Frequently, the music seems to be teetering on the edge of dissonance, but at the final moment tumbles back from the abyss into the kind of lushly chromatic writing that would much later make Korngold the dean of Hollywood’s soundtrack composers and earn him the sniffingdisregard of the nation’s avant-garde.

Conlon conducted it with obvious love (the drunken Viennese waltz in the Intermezzo movement proved a particular delight), and the Colburn students played it with an idiomatic mastery far beyond their years.

As with the other works on the program, the Korngold reminded us of how much fine, long-buried music Conlon has disinterred and how much more digging still needs to be done.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.