Nelson Mandela dies: A photo showed the world the fury of South Africa

South Africa was in chaos on Feb. 11, 1990, when Nelson Mandela was released from incarceration after 27 years as a political prisoner.

Perhaps no image encapsulates more powerfully the turmoil into which he was thrust than a brutal photograph shot seven short months later by Greg Marinovich. The picture was taken in the Soweto area of Johannesburg where Mandela lived.

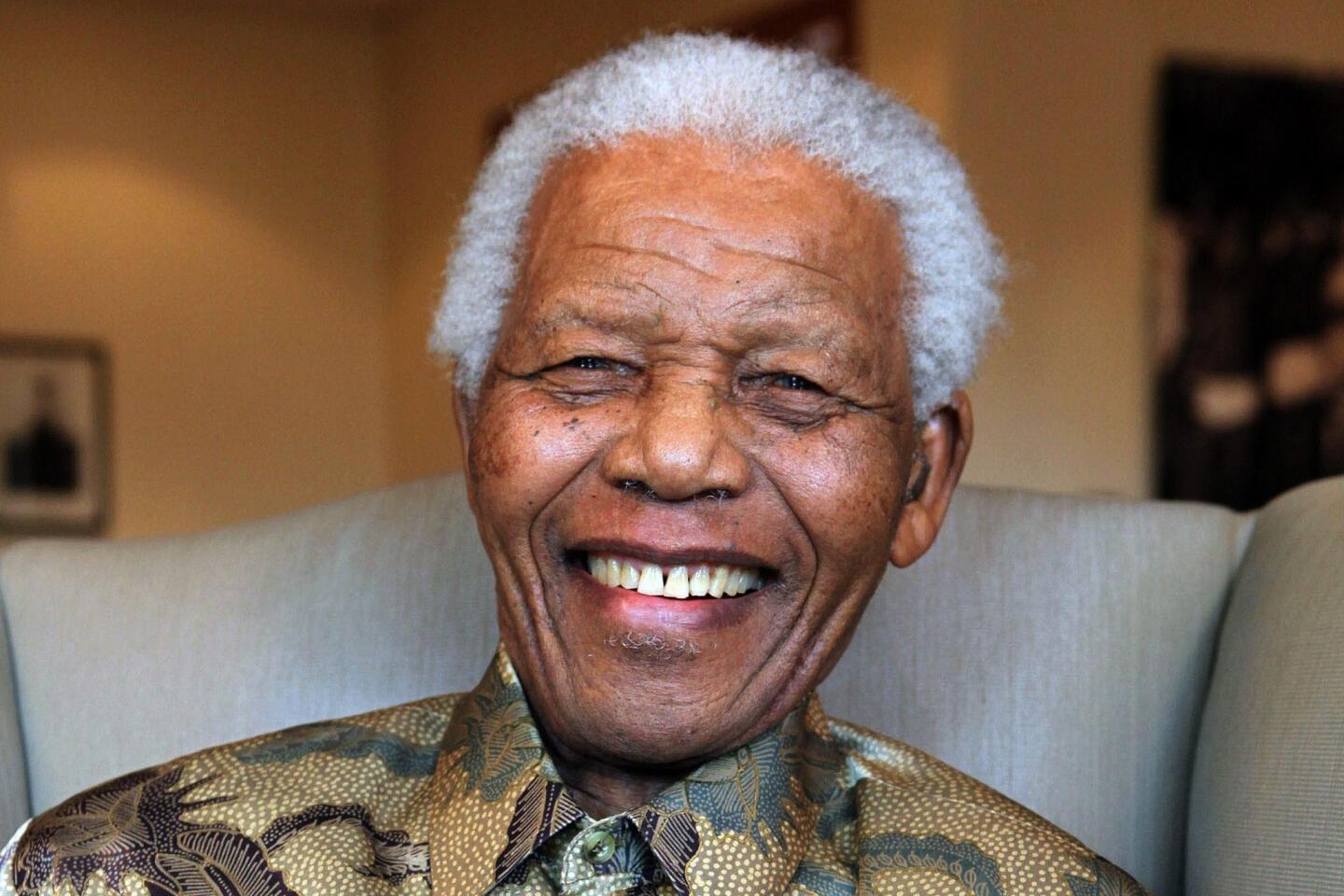

Mandela, 95, died having attained the vaunted stature of “father of his country.” Marinovich was just 28 when he took the indelible picture, an awful image that was seared into the pages of hundreds of newspapers around the world, including the Los Angeles Times. It earned the 1991 Pulitzer Prize for Spot Photography.

FULL COVERAGE: Nelson Mandela (1918-2013)

The photograph shows the murder of Lindsaye Tshabalala, an innocent but suspected Zulu spy for the Inkatha Freedom Party, by an unidentified supporter of the African National Congress, which Mandela would soon lead.

Police that day had unveiled Operation Iron Fist, mounting machine guns on armored cars and sealing off volatile areas with razor wire. The white-minority government claimed the plan was an effort to curb a month-long war among factions in black townships.

Mandela, who opposed political domination based on any race, condemned Operation Iron Fist as a plan to protect white police officers more than black township residents. By encouraging friction between the Inkatha and the ANC, the apartheid regime could use the violence to justify keeping power.

PHOTOS: Actors who’ve portrayed Nelson Mandela on screen

The police “have not addressed the issue as it affects blacks, but as it affects the lives of whites,” he told reporters.

Marinovich’s photograph, taken the same day and at roughly the same time that Mandela spoke at a news conference in his Soweto home, virtually pictured Mandela’s assertion. Four figures in an indistinct landscape dramatize what was at stake.

At the center is Tshabalala, a crouched silhouette engulfed within an orange ball of flames. He had been set on fire.

OBITUARY: Nelson Mandela, anti-apartheid icon, dies

To the left, an unidentified ANC supporter brings a weapon down on the burning man’s head. The pictured instrument is a long, blunt shadow, either a club or a machete, adding viciousness to an already unspeakable barbarism. Kill meets overkill. The fearsome if unnecessary force is italicized by the slayer’s one-legged stance, which adds leverage to the blow.

In the foreground to the right, a young boy flees the savage scene. While layering the gruesome narrative, he lends an incongruous, delicate balance to the formal composition. Slipping outside the photograph’s confining frame he visually speaks for us, relieved to be witnessing the shocking carnage only from a distance.

The fourth and final figure is not shown, except insofar as we have a photograph at which to look. Marinovich is an actor in the unfolding event. The white South African photojournalist records the deadly chaos into which his black neighbors have been plunged. For him, distance is not an option.

PHOTOS: Nelson Mandela through the years

Could he have intervened in the mob-driven murder taking place in front of his camera’s lens? The moral clarity with which apartheid’s racism could be condemned collides with the myriad ambiguities surrounding daily episodes in the struggle to end its official sanction.

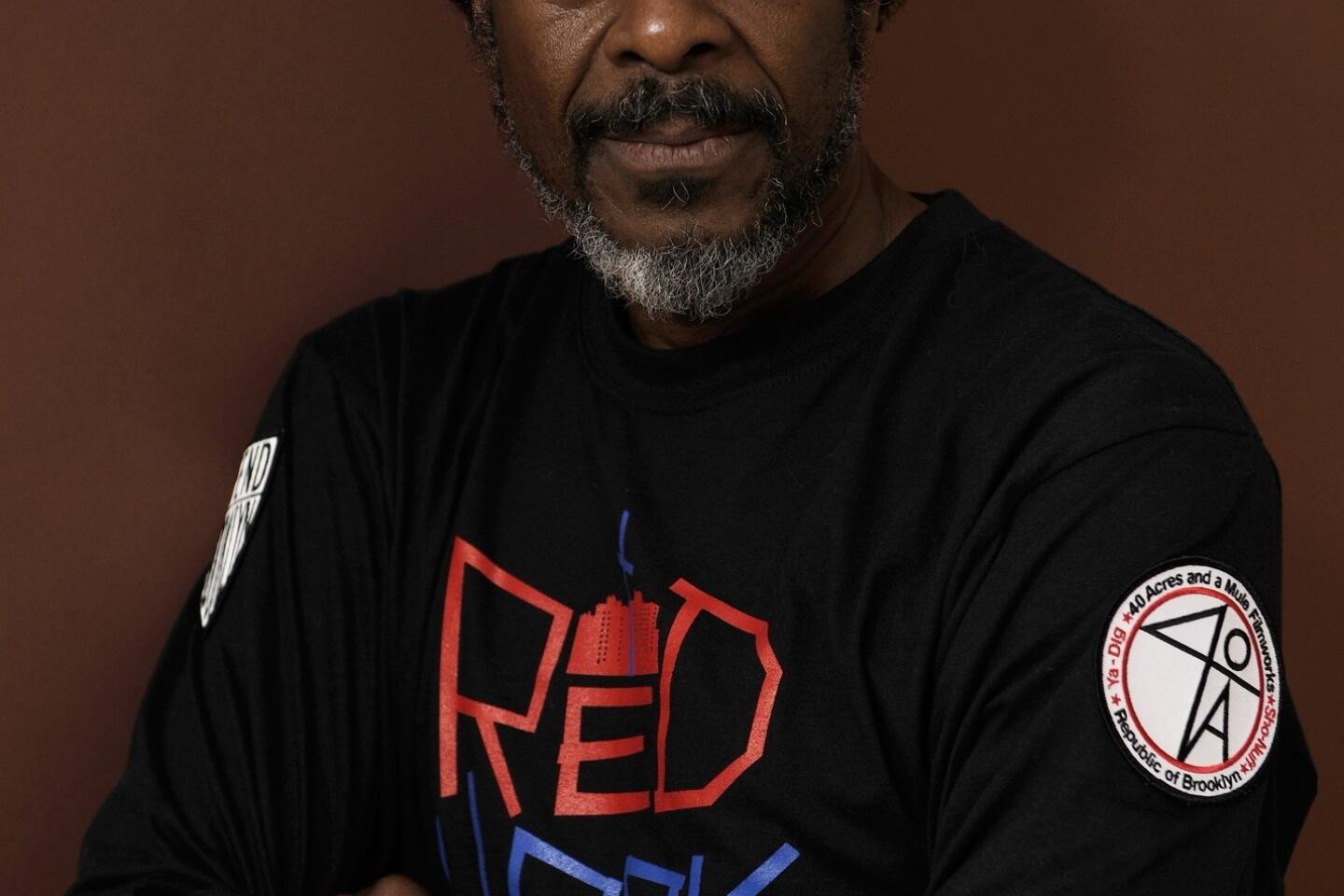

Marinovich knew that conflicted situation all too well. As a journalist, he was one of four principal members of an ad hoc group of photographers that came to be known as the Bang-Bang Club. They chronicled the period between Mandela’s release from prison and his 1994 election as South Africa’s first black president.

Work by the group was included in “War/Photography,” the engrossing traveling exhibition at the Annenberg Space for Photography in Century City last summer. (Marinovich’s Pulitzer image is included in the catalog of the show, organized by the Museum of Fine Arts Houston.) With fellow photographer João Silva, he co-authored the 2000 book “The Bang-Bang Club: Snapshots from a Hidden War.”

Of the killing the photographer later explained: “This was without doubt the worst day of my life, and the trauma remains with me, despite some 20 years and a lot of coming to terms with the incident, my role and what it means to be involved in murder.”

The apartheid government, which he opposed, used the sort of horror captured in his photograph as evidence that South Africa could not be governed by the ANC.

Soon, Mandela’s revolutionary presidency would give the lie to that claim too.

ALSO:

10 essential anti-apartheid songs

Nelson Mandela, anti-apartheid icon, dies

Zuma asks country to realize Mandela’s vision

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.