Behind the candelabra: Liberace’s bling a legacy to classical music

He was a protégé of Paderewski, the legendary Polish pianist, who said that someday this boy would take his place. But this boy became a parody. Poor Liberace.

He may have cried, as he liked to quip, all the way to the bank, but he is poor Liberace if his legacy must be reduced to the pathetic, bitchy, superficial, desperate-for-attention queen portrayed by Michael Douglas in “Behind the Candelabra.” Steven Soderbergh’s trashy biopic about the pianist and his relationship with his young chauffeur had its premiere Sunday on HBO.

FOR THE RECORD:

Liberace: An article about Liberace’s legacy in the May 27 Calendar section misidentified the HBO film “Behind the Candelabra” as “Beyond the Candelabra.” In addition, violinist Amadeus Leopold was formerly known as Hahn-Bin, not Ha Bin. —

Perhaps I should refer to Liberace the way everyone else does — as an entertainer rather than as a pianist. Even The Times obituary in 1987 began by noting, “critics were more impressed by his wardrobe than by his piano technique.” Not this critic.

PHOTOS: Lessons from Liberace - Concert dress

As a kid, I was taken — by my mother, who loved the pianist as much as the next mother — to see Liberace’s show and thought it idiotic. But the piano playing, indeed, impressed.

Years later, I happened to meet him and found Liberace to be no idiot. We had a brief and surprisingly illuminating conversation about the piano and specifically about Paderewski’s technique and interpretations. Intrigued, I asked Liberace whether he would consider doing an interview about Paderewski, and he beamed at the prospect of being taken seriously by a critic.

Then again, Liberace beamed at anyone who showed any interest in him for any reason whatsoever. The interview never took place. His suspicious handlers weren’t nearly as accommodating as the star. They couldn’t be sure this wasn’t some kind of set-up. It was painfully obvious that under all the bling and warm smiles, Liberace was fragile. His flamboyant wardrobe was his emotional armor.

This was the sensitive place behind the candelabra into which I had hoped the new film might more productively peek. Especially since classical music, as with much else in show business, happens to have entered a new era of bling.

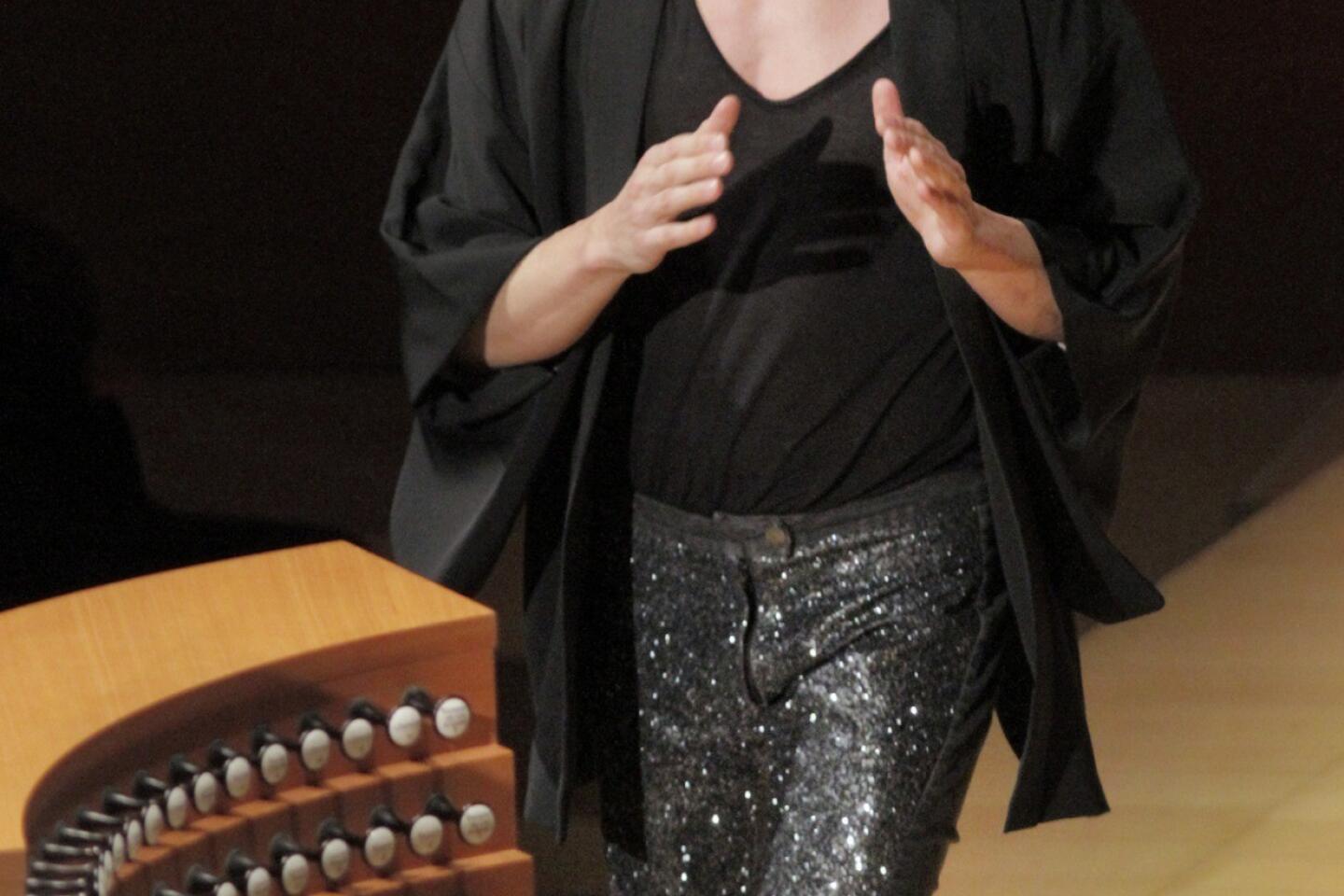

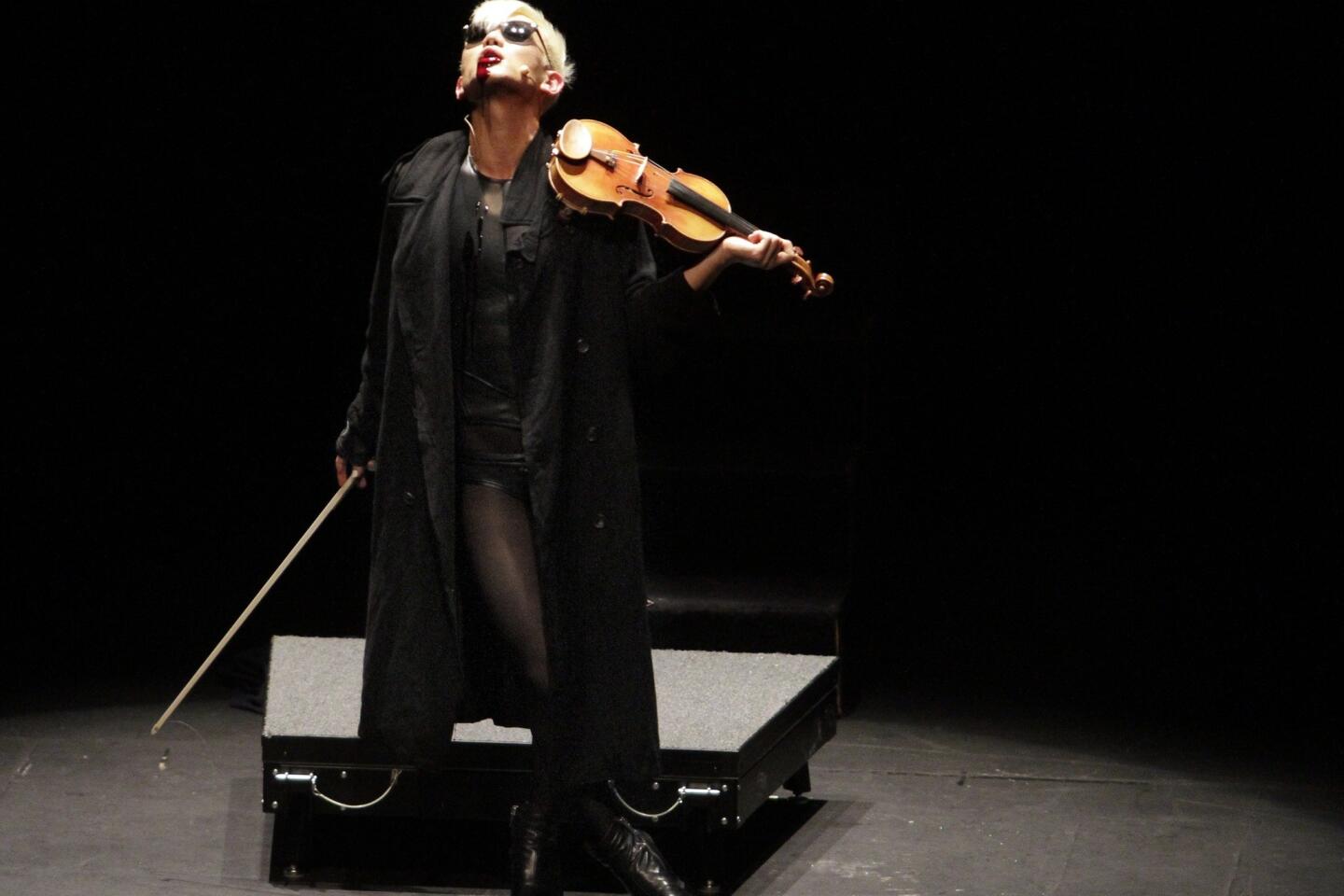

For a recent recital in staid Carnegie Hall, Yuja Wang wore the little orange dress that caused commotion at the Hollywood Bowl two years ago. Organist Cameron Carpenter and violinist Amadéus Leopold come across, in their bejeweled fashion statements, as 21st century Liberacistes. Even the sober violinist Hilary Hahn showed up this month for a Walt Disney Concert Hall recital in a gown with practically a bikini top.

PHOTOS: Liberace - From the archives

Liberace hardly invented showmanship. Maybe the ancient Babylonians did. Or the cavemen. And although traditional concert dress may be formal and conservative, there have always been outliers. In the ‘60s, Seiji Ozawa exchanged white tie and tails for a white turtleneck and beads when he conducted, and everyone thought that groovy. In the ‘70s, the Kronos Quartet made the once-stodgy string quartet stylish enough that David Bowie could feel at home sitting in with the string players. In the ‘80s, violinist Nigel Kennedy sported such a punk look that he was once turned away at the backstage door of a London concerts hall where he was supposed to be soloist with a major orchestra. He got a lot of gleeful mileage out of that.

But when Liberace came onstage wearing a 135-pound ermine coat with a rhinestone lining and a 16-foot train, that did take things a bit far. In “Beyond the Candelabra,” he says he had his eureka moment when he was about to make his Hollywood Bowl debut. Looking at the black piano and the cavernous black shell, he thought no one would see him garbed in concert black. But that’s absurd. The traditional Bowl dress is a white jacket, and the shell is lighted. His Bowl debut was in 1953, and he continued to wear normal formal concert dress throughout the ‘50s, although he had the candelabra. Nor would Liberace ever mistake a nearly 20,000-seat venue, which he sold out, for a 10,000-seat one, as he does in the film.

What really happened to Liberace was that in the ‘40s, he realized he could make more money and get more attention by charming audiences and popularizing the classics than by playing them straight. He was always on the extreme side. In his early reviews, he was accused of playing too fast and too slow, too loud and too soft. He showed off and played to please, romanticizing everything. He sounds a lot like the Lang Lang of his time.

Gradually, Liberace found a way to sell himself on image and charm. It worked spectacularly well. He was for a period the highest-paid entertainer on television. The clothes and lifestyle became his form of artistic expression. But he got caught in what he ultimately called an unending trap of continually having to outdo himself, forced to become more and more extreme to renew his act.

That doesn’t have to happen to Wang, Lang Lang, Carpenter, Leopold (who used to be Hahn-Bin, if you haven’t been keeping up with the Korean American violinist’s Madonna-approved career) or any other young fashion plates on the concert circuit. The Kronos has been annually changing its look for 40 years and has remained the most vital ensemble anywhere by commissioning hundreds of new string quartets from composers around the world.

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures by The Times

Still, concert dress is an inescapable signifier. It creates a first, if not necessarily lasting, impression. There is no greater stage magic, for instance, than when an overweight, appallingly dressed, aging soprano convinces you she is Juliet. Nor would you believe just how fast Kennedy’s punk peels away when his rapturous tone begins to evoke the pathos of Elgar’s lost Edwardian England.

The fact is, every performer is different. There are no rules. Carpenter incorporates the best of Liberace in his concert appearances. He takes style and entertainment seriously. But he also takes the organ seriously. With his new Mohawk haircut and intense playing, he was an incomparable soloist in Copland’s “Organ” Symphony with the L.A. Philharmonic last month. At the work’s premiere in 1925, Walter Damrosch said that any composer who could write a symphony like this at 23 would be ready to commit murder in five years. Carpenter looked and sounded the part.

Leopold represents the worst of look-at-me Liberace banality. He lacks charm and has already, in his early 20s, gone too far letting ostentatious fashion gaudily color his musicianship. With Liberace, you never really knew who he was — you still don’t, even after all the sex, lies and toupees in “Beyond the Candelabra.” Boastful Leopold wants you to know everything.

In Wang’s case, she has gotten flashier and less mechanical at the keyboard as she has grown increasingly comfortable sashaying onstage in sexy gowns. So far, at least, that hasn’t been a bad thing.

Orchestra players suffer inevitable psychic tolls as artists always expected to blend in. The women of the L.A. Phil who got to wear designer Azzedine Alaïa gowns during the orchestra’s recent production of Mozart’s “The Marriage of Figaro,” however, seemed to have a pleased glow about them, and there seemed something contagious about that in some particularly gorgeous playing. The orchestra had an aura that sure beat Casual Fridays.

Whether Liberace died content to have brightened the lives of a lot of people or angst-ridden about having wasted a great musical talent is a question that Soderbergh doesn’t ask. But today’s musicians, recognizing that there is no business like show business, need to ask themselves whether crying all the way to the bank is still crying.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.