Ellsworth Kelly: ‘Flexible perfectionist’ remembered by Eli Broad and museums around the world

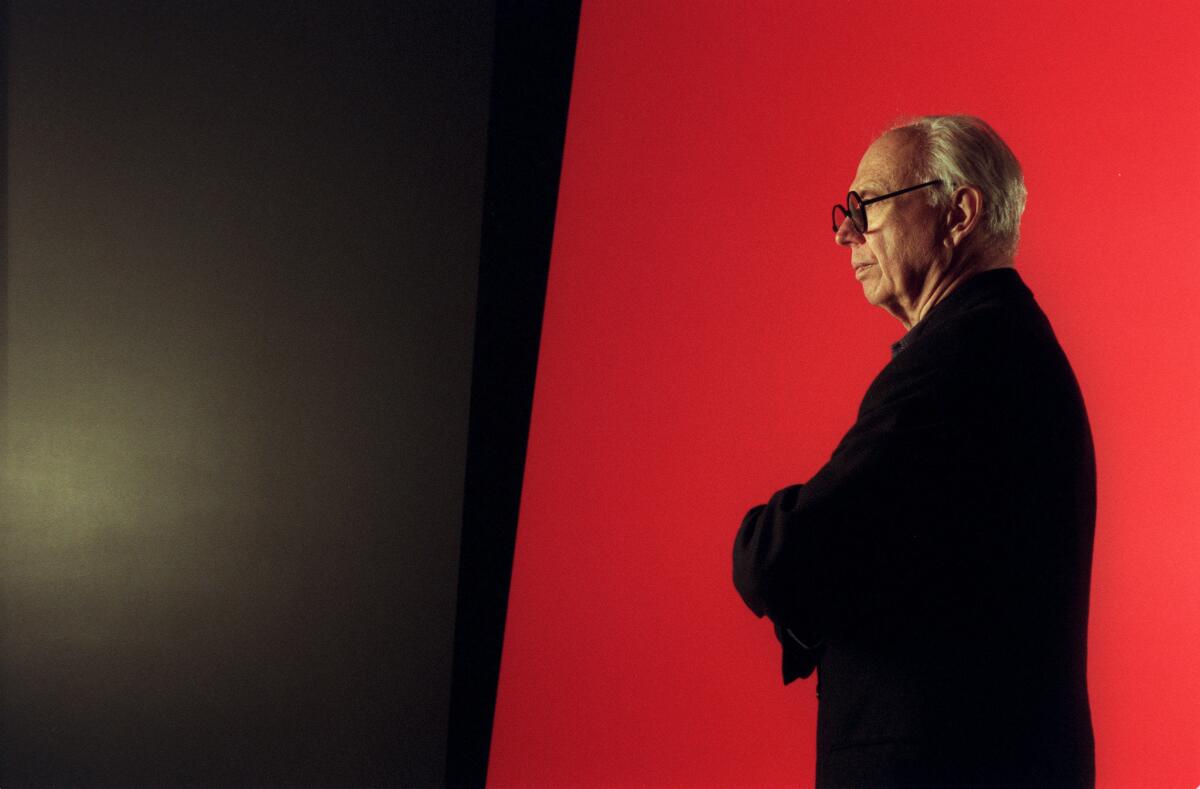

Ellsworth Kelly, photographed in 1996, died on Sunday at 92.

Two decades ago, the abstract artist Ellsworth Kelly was invited by Eli Broad to install some of his creations at the Los Angeles billionaire’s foundation in Santa Monica.

Broad recalled that Kelly spent two days overseeing every aspect of the installation — even the smallest details that many major artists would leave to assistants or curators. “He was such a perfectionist,” Broad said Monday in an interview.

The word “perfectionist” was something frequently repeated by those who knew and worked with Kelly, who died Sunday at 92.

At the same time, they fondly described him as a generous man who never stopped being curious about the world around him and who took simple pleasures in the creation of his art.

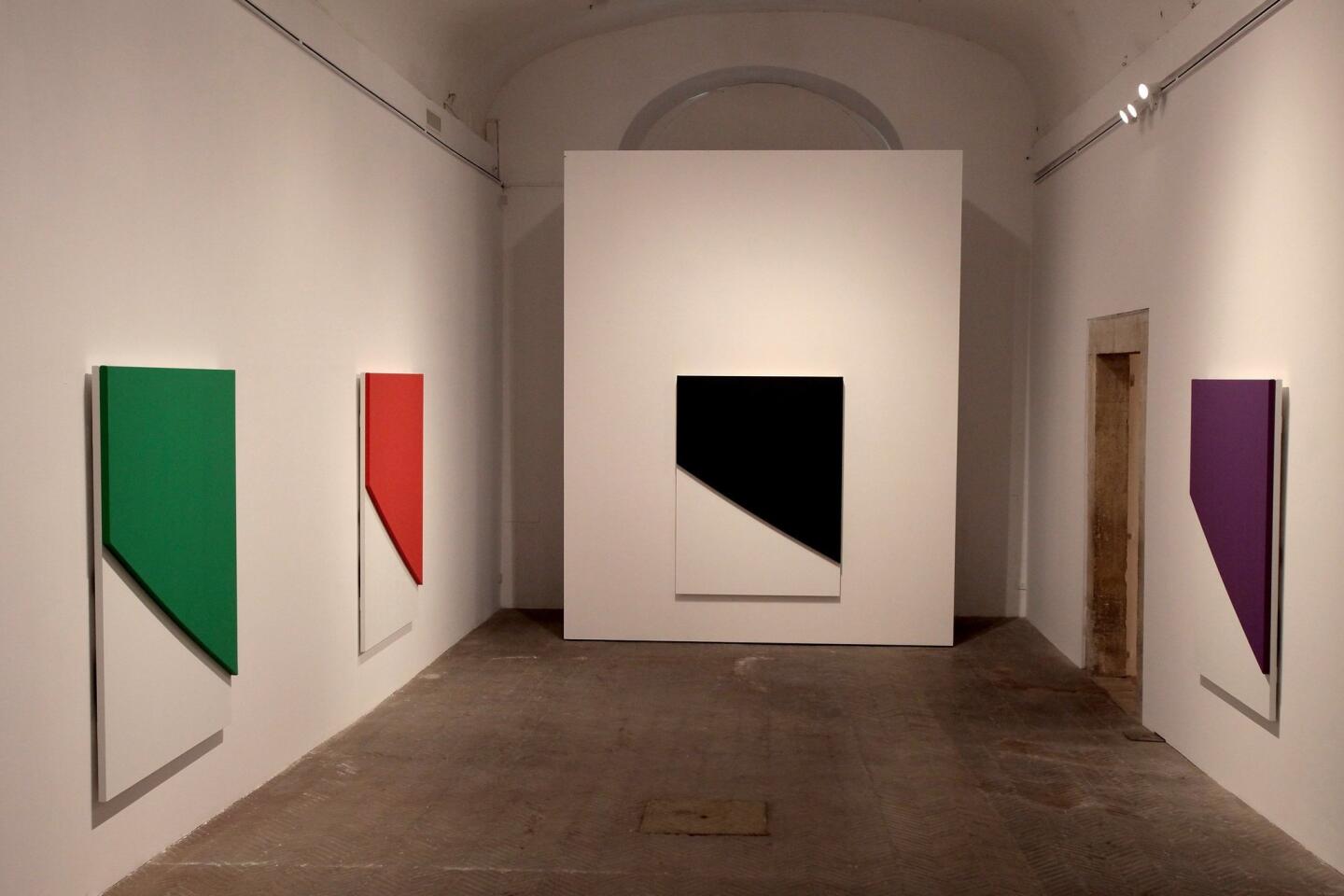

One of the leading abstract artists of the postwar period, Kelly created works of cleanly juxtaposed colors and shapes, many of which reside in major museums.

His prolific career saw forays into paintings, drawing and sculpture. For many, he ranks among the most important American artists of the last 100 years.

As with many creative titans, working with Kelly was not always a walk in the park, according to those who knew him.

“He was a perfectionist. But I would also say that he was a flexible perfectionist,” said Richard Armstrong, director of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and Foundation in New York. “He frequently had a better understanding of how to present his work than a curator.”

The Guggenheim hosted a career retrospective for Kelly in 1996 that later came to the Museum of Contemporary Art in L.A.

“When he would be working on an exhibition, he cared 100% about every last detail of placement, lighting, graphic design,” said Ann Temkin, chief curator of painting and sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

“But it didn’t come with any of the unpleasantness that you would expect to come with that. It was done in a courteous, thoughtful, respectful way.”

Kelly served in the Army in Europe during World War II. After the war, he returned to Europe to live in Paris in the late ’40s and immersed himself in the city’s modern art scene. It was perhaps the key formative experience of the young artist’s career — a period in which he absorbed the colorful creations of Matisse and other masters.

His strong association with France continued throughout his life. In 2002, the Centre Pompidou in Paris mounted an exhibition examining the relationship between the works of Kelly and Matisse.

“France held a lot of nostalgia for him,” said Bernard Blistène, director of the Musée National d’Art Moderne at the Centre Pompidou. During a recent visit to Kelly’s home in Spencertown, N.Y., “the only thing he wanted to do was talk about France and modern art.”

Kelly lived for years with his partner, Jack Shear, whom he later married. “It was a real history of love between them,” Blistène said.

In 2012, the L.A. County Museum of Art mounted an exhibition of Kelly’s prints and paintings. Despite needing the assistance of an oxygen tank, the artist traveled west to attend the opening, during which he was feted at a lunch of about 100 guests.

Stephanie Barron, senior curator of modern art at the museum, said that she spent time with Kelly in his studio.

At times, he would bring together some of his work and “study them for weeks to make sure he has the relationships right,” she recalled.

His art has “an exacting nature,” she explained, “but it also has a soul and humanity to it. It’s why they hit people viscerally — they’re not cold abstract works.”

For close to 40 years, Broad and his wife, Edythe, remained loyal collectors of Kelly’s work. Eight pieces reside in their new contemporary art museum in downtown L.A. The couple also show some of his work in their home.

“You see it as you enter. We’ve enjoyed living with it over the years,” Broad said. “He was a good friend. It’sa great loss to us personally.”

Despite living three hours outside New York, Kelly remained a palpable presence in the city’s art world. He was most recently represented by Matthew Marks, who has galleries in New York and L.A.

“He was an outgoing, gregarious and generous man,” said Hugh Davies, director and CEO of the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego. When it came to work, “he was very precise.”

It was “great to witness his continued working the last days of his life,” said Sidney Felsen, a founder of Gemini G.E.L. in L.A., via email.

He recalled an encounter years ago when he saw Kelly staring at a wall that had about 15 samples of different yellows.

“He didn’t move for approximately 15 minutes,” said Felsen. When he finally walked away, “I said to him, ‘What was that about?’ He said: ‘There are a thousand yellows, I wanted to make sure I had the right one.’”

Twitter: @DavidNgLAT

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.